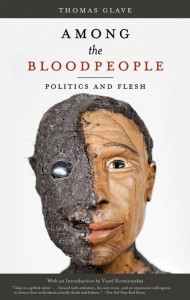

Among the Bloodpeople: Politics and Flesh

Among the Bloodpeople: Politics and Flesh

by Thomas Glave

Akashic Books. 234 pages, $15.95

Although Jamaica has a number of competitors for the description of “the most homophobic place on earth,” that’s how Time magazine characterized the country in a 2006 story. Many examples can be found in Thomas Glave’s new book, which is about the utter hatred, violence, torture, dehumanization, and other terrors perpetrated upon GLBT Jamaicans by heterosexual Jamaicans. Because there are no public meeting places, GLBT people find each other at house parties, but every situation is fraught. Many news outlets reported last July on the brutal murder of a transgender teen who was killed leaving such an event. (Whether the Jamaican Minister of Justice’s plea for the police to “spare no effort in bringing the perpetrators to justice” is carried out remains to be seen.) Bronx-born Glave was raised both in Jamaica and in New York, and he doesn’t hold back describing his love for his country and his fellow Jamaicans (the “Bloodpeople” of the title). Like his earlier book, Words to Our Now: Imagination and Dissent (2006), this book is a compilation of essays, lectures, and miscellany, most of it previously published in scholarly journals and other venues. It’s shocking to see how little has changed in seven years. Glave writes beautifully, and his occasional run-on sentences are worth the time it takes to untangle them. His highly idiosyncratic voice deserves our attention.

Martha E. Stone

Our Naked Lives

Our Naked Lives

Edited by Joseph Anthony LoGuidice and Michael Carosone

Bordighera Press. 177 pages, $15.

“I bet if you ask any Italian-American man—gay, straight, bi, whatever—what his biggest fault is,” writes Joe Oppedisano in this anthology, “he would say that it is his neurotic behavior brought on by none other than his family.” Family is definitely the subject of these essays on being gay and Italian-American, and it makes for some dramatic reading. The only two writers who claim to have no problem with the conflict between Italian tradition and male homosexuality are Michael Luongo, who claims that “Italy has one of the world’s gayest cultures,” and Felice Picano, who says that “guilt and shame are utterly unknown to me, except as concepts in literature and psychology.” That leaves all the rest—and fasten your seatbelts. There’s the pressure to be macho and fulfill a father’s view of how a boy should act, the taunts of schoolmates, the cultural stereotypes of the Italian-American male, the arguments with parents, and the sometimes long and convoluted process of coming out to them. The resulting essays are both funny and painful. They often reflect the era in which the writer grew up. John D’Emilio’s hilarious memoir of the early 70s satirizes the pressure from gay liberationists to come out to everyone, everywhere. Twenty years later, Michael Schiavi uses the work of one of those very gay liberationists, Vito Russo (The Celluloid Closet), as a bridge of understanding between him and his father. Fathers are an intense presence in these stories, though Oppedisano’s essay stands out for his mother’s incessant insistence that he was handsome, wonderful, and loved, an illusion that came crashing down when she sent him off to a friend’s birthday party wearing a sharkskin suit, only to discover that it was a pool party.

Andrew Holleran

Henry Darger, Throw-Away Boy:

Henry Darger, Throw-Away Boy:

The Tragic Life of an Outsider Artist

by Jim Elledge

Overlook Press. 400 pages, $29.95

In French, folk art is known as art brut, or “raw art,” and the work of Henry Darger certainly fits the bill. Not only because Darger was professionally untrained (he toiled most of his life as a janitor in Chicago), but because of the raw emotion and violence he depicted in a body of work comprising over 300 paintings, a massive memoir, and a 15,000-page novel recounting a gruesome war between adults and children on an alternate planet. Dick and Jane here meet Dante and Blake, with Lolita and The Book of Mormon thrown in. Darger’s work stands at the outermost limits of human creativity. It is breathtaking and disturbing and, frankly, an acquired taste. Author Jim Elledge puts Darger’s life at the center of the story, rescuing him from the armchair psychoanalysis of art historians and situating him in the history of 20th-century Chicago—queer Chicago more particularly. Elledge conveys his painstaking research into the streets where Darger grew up, the orphanages and asylums in which he lived, and the fragile personal relationships he established, notably with a night watchman, William Schloeder. Evidence is thin, though, and Elledge presses past its limits, offering lengthy passages of imagined dialogue to fill gaps in the historical record. Thus this book falls somewhere between a bold gamble and a hot mess: an assemblage of facts, conjectures, tenuous readings, and unwarranted speculations. I believed about half of it, but I’m not sure which half. Art historians may quarrel over Elledge’s reading of Darger as a gay man. And Elledge poses a broader, if unstated, challenge to GLBT historiography: people like Henry Darger barely register in the archives at all, and the task remains to recover the lives of the poor, the mentally ill, and victims of abuse who have inhabited the queer corners of American life.

Christopher Capozzola

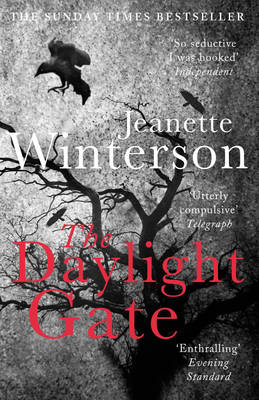

The Daylight Gate

The Daylight Gate

by Jeanette Winterson

Grove Press. 240 pages, $18.

This novel about the 1612 trial of the “Lancashire Witches” is based on a contemporary account by lawyer Thomas Potts: The Wonderfull Discoverie of Witches in the Countie of Lancashire. The word “wonderful” had a considerably less positive meaning at the time than it does now, and Potts’ account is hardly objective. Potts shared the official government view of “popery” (Catholicism) and “witchery” (broadly interpreted) as set forth by the very Protestant King James, who wrote a book about demons as part of his mission to rid England and Scotland of both. Jeanette Winterson’s account is hardly objective either, and she explains in an introduction that she has tampered slightly with the historical facts. She’s known for her historical fiction, in which love between women is often a major plot element. In this novel, the independent Lancashire gentlewoman Alice Nutter (an actual person) is acquainted with William Shakespeare, whom she had formerly welcomed into her house in London, “like a northern woman.” Generosity is Alice’s strength and her fatal flaw. While living in London, Alice was introduced to the Dark Arts and a beautiful fellow-traveler, Elizabeth, with whom she had a passionate affair. The ending of this beautifully written, heartbreaking novel is Shakespearean, but composed in the simple language of a traditional ballad. Winterson is so good at casting spells that it’s fortunate for her that she doesn’t live in an era when “witchery” was a dangerous hobby.

Jean Roberta