EXIT WOUNDS

by Lewis DeSimone

Rebel Satori Press. 371 pages, $22.95

Without resorting to rose-colored glasses, Exit Wounds unabashedly sings the praises of San Francisco. In Lewis DeSimone’s novel, it’s the adopted home of Craig, a fifty-something gay man who moved there from Minnesota in the 1990s. A bit of a commitment-phobe, Craig is single. He manages a bookstore threatened by redevelopment. His realtor friend is urging him to cash in on his now overpriced condo near the Castro, but Craig likes it where he is, within walking distance to the bars that he and his friends still frequent, less for pickups these days than for group chats over martinis.

These chats sometimes become bitch sessions. The city has gone to hell. The Castro has lost its luster, partly due to the death and devastation of AIDS. Painted-lady charm and sexiness has been replaced by gentrification and workaholism. Young gay people are ignorant of their own recent past. Abundant sexual pairing has given away to long-term relationships and diminished libidos. So Craig and his small circle of mostly longtime friends often meet over drinks and meals, at bars in living rooms and tiny gardens, and fall into the urban good life that comes from old flames, loves lost, partners made, and friendships that have survived the years. A subplot about a criminal case on which Craig serves as a juror seems a bit inconsequential, but DeSimone handles those scenes with dispatch and brings us back to his story of enduring friendships in a fast-changing city.

Claude Peck

BAD SEED: Stories

BAD SEED: Stories

by Gabriel Carle

Translated by Heather Houde

The Feminist Press at CUNY. 120 pages, $15.95

Pre-recovery, pre-therapy, the young, queer characters in Bad Seed, Gabriel Carle’s first collection of short stories published in English, have not yet sorted out their passions. The geographic center of these eight stories is the University of Puerto Rico in San Juan, specifically the theater steps, where Carle’s narrators and their friends—“the Bad Decision Club”—meet between classes. They are humanities students who study Romance languages and literary theory. Some got kicked out of the house, some can’t make tuition, some do bong hits, then work it off on the dance floor. Despite constant oversharing in the group chat, these young gay, trans, and nonbinary people suffer their problems alone. “I have no one to vent to,” says the narrator of “The Blunts That Bond Us.” “I’m not one to talk about my internal turmoil.”

While the characters go quiet with each other, Carle’s prose stays loud, and we hear it all—desperation, nihilism, anguish, obsession—in language that swells to excess. Magical weed in “Casablanca Kush” smells “super-extra fruity, a mix of strawberry-orange-lemon-mango.” The narrator of “In the Bathhouse” imagines being “burnt at the stake and vomiting demons in a nameless, timeless forest and watching a tribe push a giant fireball out of the mouth of an erupting volcano.” Carle’s hyperbolic style conveys the bloat of overconsumption that their characters experience—of TV, games, social media, porn, drugs—but the piling on of words can be tedious.

There’s excess in the storytelling, too. “Casablanca Kush” starts as postcolonial magical realism but devolves into Marvel-like fanfiction. In “Devilwork,” a metafiction, two sketched tales spiral into farcical porn involving goats, college professors, and ring lights. While each story in Bad Seed has a throughline that matters, it is often buried by excess.

Lori O’Dea

THE WORK OF ART

THE WORK OF ART

How Something Comes from Nothing

by Adam Moss

Penguin Press. 431 pages, $45.

Adam Moss’ book is a collection of interviews with 43 artists, many of them gay, on how they make their work, using iconic examples to illuminate their process. The author’s aim is “to render the experience of creativity—that is, the frustration, elation, regret, first glimmers, second thoughts, distress, and triumph that leads to works of art.” Conversations are augmented with notebook entries, napkin doodles, early sketches, reams of false starts, iPhone photos, lyric fragments, and other ephemera illustrating the alchemical process of artistic conjuring.

Tenacity and resilience abound throughout this beautifully designed compendium. Author Michael Cunningham shares multiple drafts of what became his Pulitzer Prize-winning The Hours. Tony Kushner details free associations, chance happenings, practical constraints, and deep listening to his characters (“I was just taking dictation”) as Angels in America develops. The late Stephen Sondheim recalled dropping a song from Company for its out-of-town tryout and having one week to come up with “Getting Married Today.” Fashion designer Marc Jacobs proclaims the virtue of deadlines: “Time becomes the greatest editor. The only way to get things done is to finish.”

Back stories by pioneering journalists are quite satisfying, such as excerpts from Wesley Morris’ discursive “My Mustache, My Self,” a 2020 essay in The New York Times on Black identity and masculinity. Also fun are Morris’ snippets gleaned from notes written in the dark while viewing films. Other photographers, architects, chefs, puzzle masters, songwriters, radio hosts, sculptors, and graphic designers complement the treasure-trove. The appendix is chock-a-block full of glorious artifacts, including handwritten revisions of Whitman’s Leaves of Grass.

John Killacky

ROUGH TRADE

ROUGH TRADE

by Katrina Carrasco

MCD. 385 pages, $28.

I’m not familiar with the Pacific Northwest and didn’t know that Tacoma, Washington, is a busy port city. In the late 19th century, in fact, its port was at the heart of the opium drug trade, if you’re to believe the world imaginatively created by Katrina Carrasco in Rough Trade, her second book in a series about opium trader Alma Rosales. The details of this elaborately invented world feel as real as anything you’d see in front of you. It’s a world that’s colorful, reckless, dangerous, and sexy.

Alma oversees a crew responsible for delivering large amounts of opium, but she does so using the persona of Jack Camp, a male lieutenant within the organized crime ring running the drug trade. Trouble arrives when law enforcement investigates a murder on the docks and comes perilously close to sniffing out the drug trade. The main action of the book is Alma/Jack’s efforts to prevent that from happening. There’s action also in the town’s queer bar, Monte Carlo, where gender bending is welcome and where Alma feels at home.

The novel is most interesting when Alma interacts with her ex-lover Bess, a former detective with the Pinkerton agency. The story of Alma and Bess can be found in the first book in this series, The Best Bad Things, though you don’t need to have read the first book to enjoy the second. Delphina, the boss of the organized crime outfit running the opium trading, also has a complex relationship with Alma. With both women, questions of loyalty, trust, betrayal, love, and lust are tossed around with plenty of clever dialog. This and the intricate world-building are the strengths of the novel, which benefits greatly from its setting in time and place.

Anne Laughlin

WHERE THE FOREST MEETS THE RIVER

WHERE THE FOREST MEETS THE RIVER

by Shannon Bowring

Europa Editions. 336 pages, $18.

Shannon Bowring follows her absorbing, award-winning The Road to Dalton with Where the Forest Meets the River, another stellar, gimlet-eyed gaze at living in a small town and wrestling with family, memory, love, and identity. It’s the summer of 1995, five years since the devastating unexpected death of 26-year-old Bridget Theroux. A cloud of residual grief and guilt still shrouds the close-knit community. Having used Sherwood Anderson’s Winesburg, Ohio as a template for a series of linked short stories, Bowring brings back many of the characters from the first novel.

After his first year at the University of Maine, nineteen-year-old bisexual Greg Fontin returns home to be the best man at his sister’s wedding and to work at the family hardware store. He is reluctant to do both, still harboring the secret of his sexual identity and not wanting to be trapped in a job he hates. His overwhelming desires are to be a horticulturist and allowed to “love who you love.” His closest friend, a forty-something married librarian named Trudy Haskell, understands his subverted passions because they resemble her own “longtime best friend” of more than twenty years, Beverly Theroux, a married woman. Trudy and Bev share a love “so much deeper and more complex than a friendship, or an affair, or even a marriage. Maybe especially a marriage.“

While it’s not completely necessary to have read the first novel, doing so contributes essential back stories and clarifies the emotional maelstrom of the residents in this melancholy, bittersweet sequel with hopes for a trilogy.

Robert Allen Papinchak

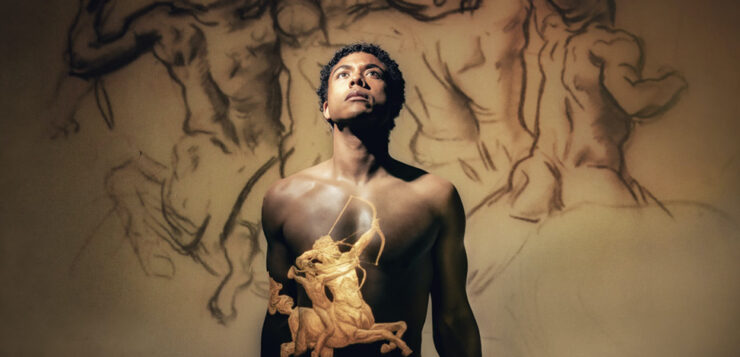

AMERICAN APOLLO

Des Moines Metro Opera Festival and Blank Performing Arts Center, Indianola, Iowa

July 13–19, 2024

When John Singer Sargent’s nude portrait of Thomas McKeller was revealed to the world in 2020, it incited speculation about the artist’s sexuality and his relationships with his male models. Ignacio Darnaude, who wrote about the painting in this magazine (Sept.-Oct. 2021 issue), characterized it as the pièce de résistance in a trove of “intimate, sensual, voyeuristic, and openly homoerotic male nude drawings [that]surfaced after [Sargent’s] death.” For many, the painting betrays Sargent’s romantic feelings for McKeller, a young African-American bellhop whom Sargent used as the body model for his classically-themed murals at Boston’s MFA.

Sargent and McKeller’s relationship is the subject of American Apollo, a new opera composed by Damien Geter with a libretto by Lila Palmer, which had its world premiere at the Des Moines Metro Opera Festival on July 13, 2024. The opera dramatizes the possibility that Sargent and McKeller had a years-long love affair, albeit one strained by racial and class differences—and by the fact that McKeller’s personal and racial identity is erased in the murals. The result was a poignant, tender opera, anchored by rising star baritone Justin Austin, who sang the role of McKeller with captivating intensity. Geter’s eclectic musical score, which ranged from classical impressionism to blues jazz, sonically charted McKeller’s constant movement between Sargent’s rarefied studio and the African-American spaces of early 20th-century Boston.

Although the stage was typically dominated by life-size versions of Sargent’s famous paintings, it soon became clear that this is McKeller’s opera, not Sargent’s. “He wants me to be a god,” McKeller says about Sargent after one of their early meetings, subtly hinting at his awareness of Sargent’s complex, and ultimately untenable, feelings toward his favorite male model.

Joseph M. Ortiz