Derek Jarman’s Angelic Conversations

Derek Jarman’s Angelic Conversations

by Jim Ellis

University of Minnesota Press.

303 pages, $21.95

It has been seventeen years since Derek Jarman died of AIDS-related complications, but the British filmmaker’s reputation only seems to grow with time. Many queer filmmakers, from Pedro Almodóvar to Todd Haynes, appear to be under his unmistakable influence. In Derek Jarman’s Angelic Conversations, author Jim Ellis places Jarman’s basic æsthetic traits—notably his tendency to be counter-cinematic and irreverent in his approach to filmmaking and storytelling—in a political context. This is crucial, given that Jarman was an artist whose work was steeped in ideology, and that he was struggling with HIV in Britain during the Thatcher years. There was plenty to be pissed about. And Ellis gets into it, making clear artistic connections between Jarman’s work and the work of other directors, including Haynes and Pasolini. The author also deftly intertwines Jarman’s æsthetic sensibility with the radical movements raging in Britain at the time, from queer groups to the punks, indicating in great detail how they informed one another. It’s an exhaustive study, and a welcome one. And while Ellis’s writing is elegant and concise, it is aimed primarily at the academic reader. Ellis has composed a dense, intelligent reflection on Jarman’s œuvre, a fitting ode to such an iconic artist and his ongoing legacy. It is a book that Jarman fans will greatly appreciate, and one that does justice to the filmmaker’s achievement.

Matthew Hays

Gay Shame

Gay Shame

Edited by David M. Halperin & Valerie Traub

University of Chicago Press.

395 pages, $29. (paper)

As the editors of the anthology Gay Shame point out, the term “gay pride” has proven a crucial one in the GLBT movement. It has meant moving toward “liberation, legitimacy, dignity, acceptance, and assimilation, as well as the right to be different,” as they argue in an introductory essay. But the term has complex ramifications. The very notion of gay pride parades has led to commercialization around corporate and media sponsorships, underscoring the growth of a pervasive consumerism in the gay subculture. Through discussions both academic and not, the editors have gathered a broad range of contributors to discuss notions of shame and pride, to further analyze how concepts of some kind of ideal pride may in turn create other kinds of shame. The results are pleasingly disparate, including the late Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick’s meditation on 9/11 and Henry James, David Caron on Marlene Dietrich, and Amalia Ziv on cross-gender queer sex in lesbian erotic fiction. Especially impressive is Deborah Gould’s historical analysis of “shame in gay pride in early AIDS activism,” and Robert McRuer’s reflection on the intersection between disability and queerness. This anthology invites us to think about what precisely the mainstream success of gay liberation has meant, and how newly marginalized communities have formed in its wake.

Matthew Hays

Ballets Russes Style: Diaghilev’s Dancers and Paris Fashion

Ballets Russes Style: Diaghilev’s Dancers and Paris Fashion

by Mary E. Davis

Reaktion Books. 256 pages, $29.

The curtain on Sergei Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes, whose centenary was in 2009, shows no signs of falling. Mary E. Davis, music professor at Case Western Reserve University in Ohio, has mined several academic archives for this book, a fascinating look at the ways in which early 20th-century Russian dancers in France caught the public imagination. She explores how ballet costumes mutated into street clothes and how the latest Parisian designs were sometimes seen on stage. Dress designers, magazine editors, musicians, and wealthy sponsors all played their part. Beautifully illustrated on heavy stock, this book’s small size sometimes does an injustice to the more detailed images. Of many quotable scenes in this book, one stands out. Ida

Rubinstein, who had her own troupe for a short time, danced in the early years of the Ballets Russes. She created the role of Cleopatra, based on Théophile Gautier’s short story, “One of Cleopatra’s Nights.” On stage, she emerged from a mummy case after twelve veils were removed. Ballets Russes designer Léon Bakst had originally conceived of a nearly nude costume, which had to be toned down to please censors. After some modifications, her costume was adapted by designers, so that bare arms and necks, a lack of corsets, and the wearing of tunics became everyday street wear. Although this book is not about disclosing sexualities, it’s important to note that not only was the Russian-born Rubinstein a lesbian, but she was also part of the Natalie Barney salon. Another salonista was the fabulously wealthy Winnaretta Singer, who was elevated to royalty through marriage; as Princesse de Polignac she was one of Diaghilev’s most generous sponsors. One of her affairs was with the artist Romaine Brooks; one of Brooks’ lovers was Ida

Rubinstein. This book is a serious work of scholarship that sheds new light on a fascinating cast of characters. (For more on Diaghilev’s life story, see feature piece by Dean Wrzeszcz in this issue, page 28.)

Martha E. Stone

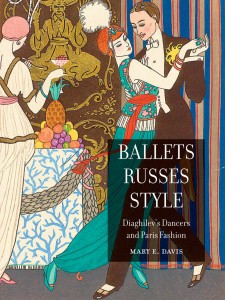

Mustn’t Do It

Mustn’t Do It

by Jo M Van Ijssel de Schepper Becker

Translated by Laurence Senelick

Broadway Play Publishing. 62 pages, $12.95

Reading Mustn’t Do It, Dutch playwright Jo M Van IJssel de Schepper Becker’s coming-out drama, feels like rereading something that you vaguely remember from high school. Of course that makes sense since we’ve all read—and seen—this story countless times in books, on stage, and in made-for-TV movies. I suspect the play seems especially dated in the Netherlands given today’s broad acceptance of GLBT folks there, but despite the work’s advanced age—it was published in 1921—the struggles of the family depicted here, particularly those of the parents, come across as eerily modern. The son’s disclosure that he’s gay places the provincial middle-class family inside that familiar triangle bounded by parental love, religious condemnation, and what-will-the-neighbors-say shame. As one of the earliest plays on the subject, Mustn’t Do It accepts the gloomy assumption that nothing but a sad and lonely life awaits the protagonist, who sees leaving home as the only way to spare his family the daily torture that his sexual orientation will undoubtedly cause. Given both the social climate of that era, and the tragic rash of suicides by gay youths in our own, his decision to seek acceptance “somewhere out there”—as well as refusing to ruin his girlfriend’s life by entangling her in a lie—glows authentically with both desperation and bravery. Tufts Professor Laurence Senelick’s new English translation serves the piece well. The mother’s rabid defense of her offspring, the father’s jealousy of their relationship, and the son’s hopeless feelings of “otherness” all seem as freshly possible today as they did eighty years ago.

Eddie Sarfaty