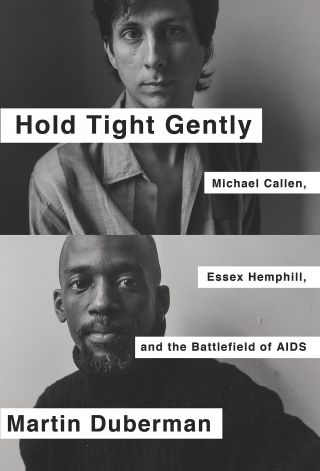

Hold Tight Gently: Michael Callen, Essex Hemphill, and the Battlefield of AIDS

Hold Tight Gently: Michael Callen, Essex Hemphill, and the Battlefield of AIDS

by Martin Duberman

The New Press. 368 pages, $27.95

SINCE THE LATE 1990s, I have seen the smiling faces all over town. Not my fellow D.C. residents—generally a serious and suspicious lot—but the faces of drug company actors in ads for the latest AIDS medicines. Whether beaming from the sides of bus stops or riding bikes through the pages of the local gay newspapers, these actors convey one message: Look how happy we are on the latest drug cocktail. Look how little you will need to adjust your lifestyle because you have this virus. Look how much control you have over AIDS.

I suspect Martin Duberman also has these ads in mind in his latest book, Hold Tight Gently

The choice of Callen and Hemphill to tell the story is an interesting strategy but raises some difficulties. Unlike the subjects of Duberman’s previous dual biography, A Saving Remnant: The Radical Lives of Barbara Deming and David McReynolds, Callen and Hemphill were not friends, lived in different cities—Callen in New York and L.A. and Hemphill largely in Washington, D.C.—and may have been entirely unaware of each other’s work. While Callen was thoroughly immersed in AIDS activism, Hemphill addressed the disease much less frequently, and was largely private about his own health struggles. Except in his poetry, Hemphill’s sense of privacy extended to the rest of his life, making his story harder to tell.

On the plus side, Duberman’s choice of biographical subjects allows him to discuss the response to AIDS both in the white and in the African American community. And while Callen and Hemphill take center stage, Duberman finds ample space for concise and compelling portraits of some of their closest friends and collaborators: Joseph Beam, Rich Berkowitz, Richard Dworkin, Wayson Jones, Michelle Parkerson, Marlon Riggs, and Joseph Sonnabend. These side-stories flesh out the narrative of Callen and Hemphill’s lives, their art, and the effect that AIDS had on them.

Duberman only returns obliquely to his subject of the contrast between previous and current approaches to AIDS. And because Callen and Hemphill’s lives were not otherwise intertwined, Hold Tight Gently is best read as a pair of shorter biographies. Duberman moves Callen’s story efficiently from his uncomfortable childhood as an effeminate boy in Ohio through his awakening as a highly sexed gay man in college in Boston and on to New York City. There, he became a frequent visitor to the office of Dr. Joseph Sonnabend and was diagnosed with a variety of STDs, eventually becoming one of the early confirmed cases of what would soon be known as AIDS.

Throughout the rest of the book, Callen’s outsized perseverance looms large, whether working to increase AIDS awareness and develop more treatments, fighting to preserve his own life, or pursuing his singing career (highlighted by his work with the Flirtations and a posthumous solo album constructed during the waning months of his life). Much of the story Duberman tells about the public response to AIDS has been told before, but his detailed account of ACT UP’s in-fighting, particularly surrounding its Treatment & Data committee, provides a useful dose of reality to offset recent hagiographies. He also shows admirable evenhandedness in addressing Callen’s adherence to currently unfashionable multifactorial theories on the cause of AIDS.

Duberman notes that Hemphill’s story was harder to uncover, but because the connection between his life and his art was so intense, Hemphill’s poetry helps supplement his smaller archive of letters, journals, and personal statements. Hemphill began writing during his teenage years, and Duberman appears to have had access to all his known work, both published and unpublished. (The title Hold Tight Gently comes from the section of poems about AIDS from Hemphill’s unpublished manuscript Domestic Life.) By weaving excerpts from the poems into the narrative, Duberman allows Hemphill’s artistic voice—at first tentative, though questing, and later fierce and uncompromising—to help explain his personality.

Determined to give his life only to art, Hemphill produced a large body of work in his short life: the poems for which he is best known, penetrating essays, an unpublished novel, film appearances (notably in Marlon Riggs’1989 movie Tongues Untied), and editing the anthology Brother to Brother (1991), the circumstances of which are detailed here and show Hemphill’s dedication to his friends and to the black gay community. However, he was not afraid to criticize the African-American community for its homophobia and the gay community for its racism, among other shortcomings. Hemphill once described himself as “a Black faggot who won’t hush his mouth.” Duberman’s biography is an engaging retelling of his outspoken life and leaves no question as to Hemphill’s lasting influence on gay culture.

Philip Clark co-edited Persistent Voices: Poetry by Writers Lost to AIDS and serves on the board of Washington D.C.’s Rainbow History Project.