ON AUGUST 19, 2018, San Francisco’s Nob Hill Theatre, one of America’s oldest venues for gay-oriented adult entertainment, shuttered its doors. This sad event marked the demise of another venue that had survived decency campaigns since the mid-20th century and urban renewal threats since the late 1970s.

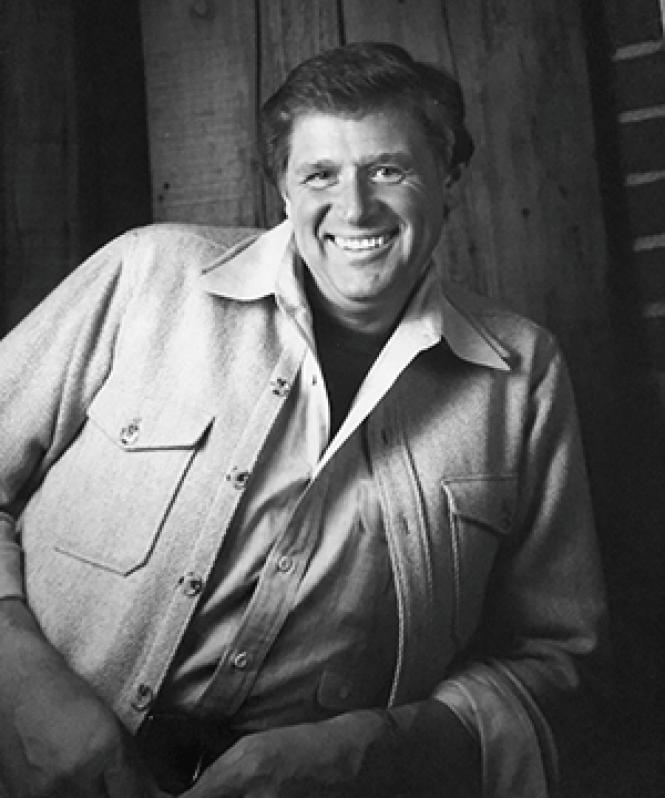

Science fiction writer Samuel Delany argued in Times Square Red, Times Square Blue (1999) that adult entertainment venues had served as institutions for sexual education and community formation for marginalized populations, including LGBT ones, for many decades. Delany was talking specifically about New York’s adult theaters, but his assertion can be generalized to West Coast venues as well, such as the Nob Hill Theater in San Francisco, which was at the forefront of gay male entertainment. Often overlooked are the innovations of Shan Sayles, the man responsible for the Nob Hill’s shift to an “all-male” film policy and who was a major figure in the emergence of American gay cinema. Sayles produced landmark queer films, including Song of the Loon (1970) and Tom DeSimone’s The Collection (1970), and he expanded his theater chain to provide new venues for gay audiences across the nation.

In the 1960s and ’70s, LGBT content was not widely available through mainstream media platforms such as cinemas or television. While gay print media such as homophile and physique magazines had circulated for some time, the widely advertised Boys in the Band (1970) is often recognized as the first overtly gay film. However, before its release and preceding the Stonewall uprisings of June 1969, there was a deluge of same-sex movies in the Los Angeles area that were produced and distributed independently from the Hollywood studios. The L.A. gay community figure and film director Pat Rocco is rightly acknowledged as a pioneer in gay independent filmmaking. Yet Rocco’s movies were part of a larger movement that included early groundbreakers in the physique genre—Bob Mizer and Dick Fontaine—and later filmmakers such as Tom DeSimone, Barry Knight, Dick Martin, Warren Stephens, and Joe Tiffenbach.

Arthouses were theaters known for screening European imports to an educated elite, but gained a more suggestive connotation by the 1950s when they began to promote their films as more sexually tantalizing than domestic productions. After working in numerous capacities for theaters in Michigan and California, in the late 1950s Sayles became the manager of the Apollo, an arthouse on Hollywood Boulevard in L.A. He moved on to manage a general release theater called the Lido on West Pico, which he converted to an arthouse format. He boldly scheduled the film L’Amant de Lady Chatterley (1955), a French adaptation of D. H. Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover. The film was controversial and effectively banned by New York’s censorship board, and in 1958 a New York Court of Appeals upheld the ban, condemning the film for presenting adultery “as being right and desirable for certain people under certain circumstances.” But then, only a few months before Sayles’ scheduled release of the film, the New York ban was struck down by the U.S. Supreme Court in Kingsley Int’l Pictures Corp. v. Regents (1959).

Sayles’ greatest influence was undoubtedly as president of the theater chain and management company Continental Theatres from the 1960s through the ’70s. The company commenced operations around 1960 with its first theater, the Vista, located at 4473 Sunset Drive. Open since 1923, the Vista was already historic by 1959 when Variety reported that it was bought by a Detroit exhibitor and a “group of private investors.” (While not named in the article, this probably involved Sayles, given his previous experience in Detroit cinema management.) In December 1959, the theater was renamed the Vista-Continental and shifted to an arthouse format. From then on, Sayles and fellow exhibitor Violet Sawyer co-operated the Vista-Continental, and the two programmed European art films and also continued to screen Soviet imports for an already established Russian immigrant community.

Meanwhile, in mid-1960, Alex Cooperman, a foreign film distributor who had previously worked for distributors in the Eastern states, acquired the Apollo Theater that Sayles had formerly managed for the Fox West Coast chain. Under Cooperman, the theater became the Apollo Arts and was changed to an arthouse format. By the end of 1960, Cooperman and Sayles joined forces with local lawyer-entrepreneur Eugene Berchin to acquire the Carmel Theater on Santa Monica Boulevard. The three re-opened the theater as an arthouse and incorporated their venture as the Paris Theater. Continental Theatres continued to expand as an arthouse circuit, and by 1964 the company added Samuel Decker as a partner to handle real estate services and acquisitions. As the theater holdings expanded under differing direct ownership, Continental also began to operate as a management company for numerous corporations that it did not own, including: Crescent Theatres, Paris Theater, Sawyer Theatres, Sayles Brothers Theatres, and Signature Theatres.

Profits soared for Continental’s arthouses. What contributed most to their success was not so much the high-class trappings of European art cinema as it was the risqué connotations of the films from countries like France and Sweden. By the early 1960s, sexual subject matter and nudity in motion pictures were increasingly permissible due to High Court decisions such as the aforementioned Kingsley v. Regents and a New York Court of Appeals case, Excelsior Pictures Corp. v. Regents of Univ. of State of N.Y. (1957), which held that “nudity in itself and without lewdness or dirtiness is not obscenity in law or in common sense.” To satisfy a growing demand for such films and to save costs on importing European reels, American art cinemas began to program independently produced American films of the so-called “nudie-cutie” and sexploitation variety. Continental was at the forefront of this strategy, and by the mid-1960s its flagship trio, the Apollo, the Paris, and the Vista-Continental, had all shifted to American-produced sexploitation pictures. For some time, the Paris and the Vista-Continental primarily programmed silent nudie features produced in-house, which increased profits because it eliminated the expenses accrued when renting outside productions from a distributor.

In the latter half of the 1960s, Continental began to curate programming for the area’s gay audiences that had been frequenting their theaters for a number of years. During this time, when same-sex intimacy was met with extreme censure by the general public, movie theaters provided one of the few places where gay men could cruise, meet up, and have sexual contact with a reduced risk of arrest or harassment. However, the Paris had run-ins with law enforcement even before it was acquired by Continental because it became known as a haven for gay men. The L.A. County Board of Supervisors attempted to close it down throughout the 1950s but was ultimately unsuccessful when its actions were ruled arbitrary and unwarranted by a California appellate court in 1958. As early as 1966, Continental began catering to the area’s gay theatergoers by initiating programs of physique films, swishy spoofs, and camp icon retrospectives. In October, the Apollo Arts Theatre presented “M-u-s-c-l-e-r-a-m-a: An Evening of Physique Films,” which featured famous body builders from Canada and England and a picture titled Beefcookie. This was followed by several other programs at the Apollo Arts, starting with “The World’s First Camp-Out!” in December, which included Herb Danforth’s camp feature Why the West Was Fun, a European sword-and-sandal film, physique shorts, and documentary footage of a homophile activist event from earlier that year. Ads for the “Camp-Out” program in the L.A. Times proclaimed “Gay Colorful Films for the Mature Male!!”—one of the first cases of a mainstream paper using the word “gay” to target this population.

Sayles’ early ventures into gay programming are often forgotten in histories of gay pornography, overshadowed by Continental’s later transition of the Park Theater on Alvarado Boulevard to a gay film venue. In early 1966, Continental purchased the Alvarado Theatre in MacArthur Park, and Daily Variety reported that this was its tenth acquisition. On April 6, the theater re-opened as the New Luxurious Park with a double-feature of the Hollywood studio films Flight of the Phoenix (1965) and What a Way to Go (1964). Initially showing early Hollywood fare at cheap prices around the clock, it soon shifted to sexploitation films. Beginning in early 1967, the Park acquired the moniker “Home of the Sun-Camp Films” when it featured only nudist films for several months. Now a legendary event in the history of gay cinema, Sayles shifted the Park to a gay film policy in June 1968 with its “First Gay Film Festival” as advertised in a two-page spread in the Los Angeles Advocate. This first gay program featured underground films by Kenneth Anger, the Mekas brothers, Andy Warhol, Jack Smith, and Shirley Clark, along with erotic shorts by Pat Rocco and Andy Milligan. In the coming months, the theater continued to exhibit gay shorts from local studios including those of Pat Rocco and Bob Mizer, and would eventually commission feature-length productions.

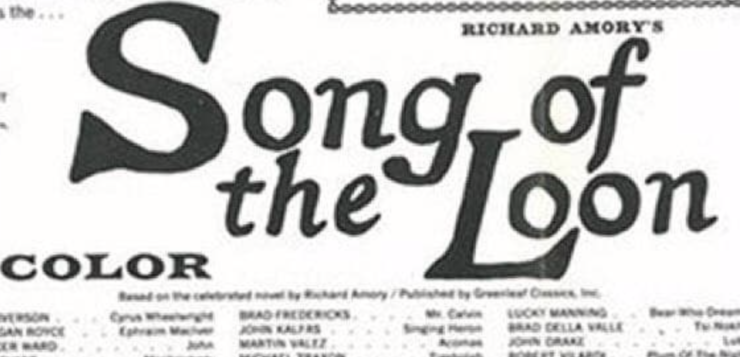

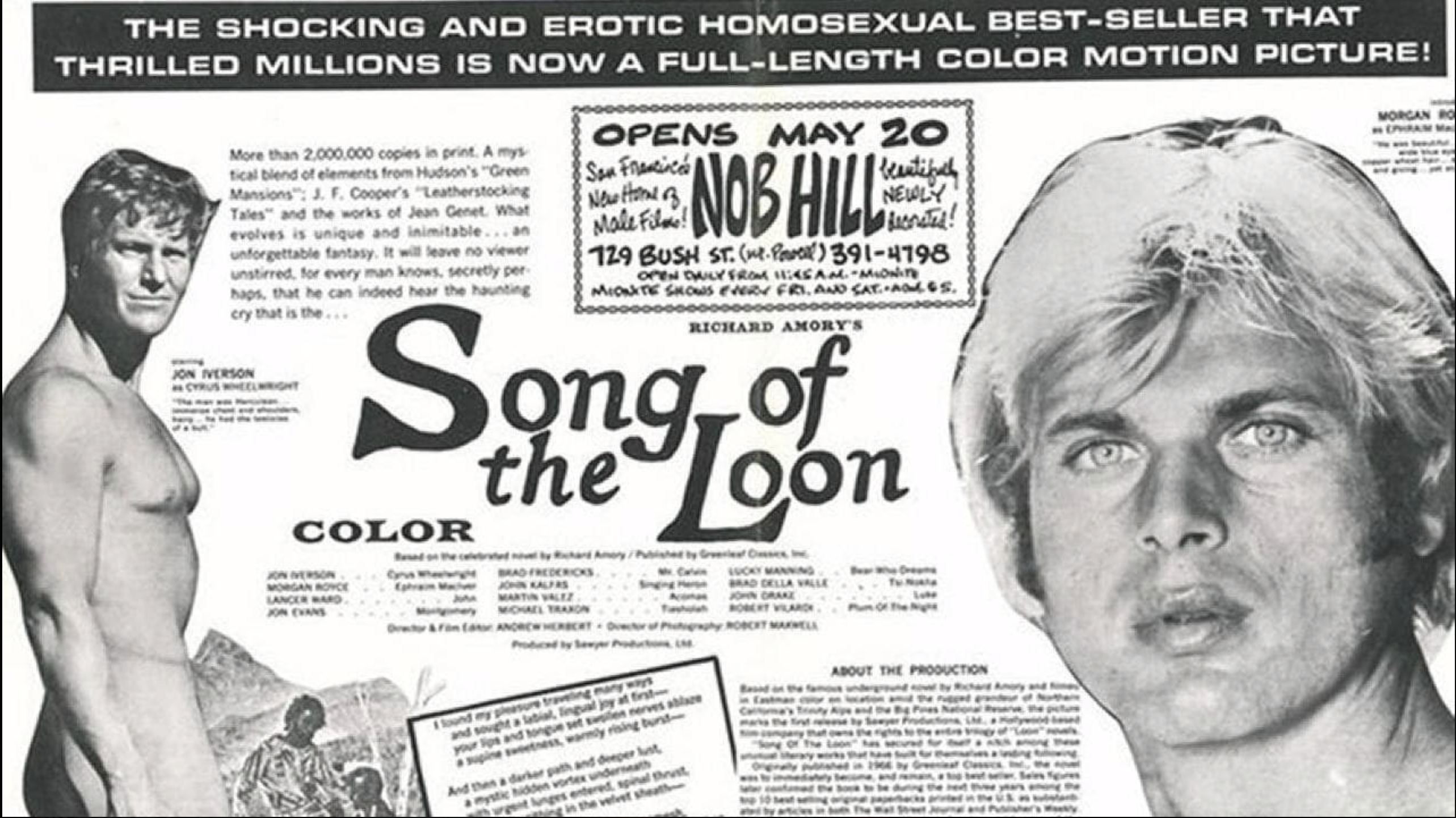

By the end of the 1960s, Continental had formed its own production and distribution arm, Signature Films. Legendary directors Tom DeSimone and Nick Grippo were involved with Signature’s early operations. Continental premiered DeSimone’s The Collection in 1970, an all-male adaptation of William Wyler’s The Collector (1965). Signature also released notorious gay roughies like Pledgemasters (1971), an exposé of fraternity hazing, and Highway Hustler (1971), a rough trade narrative that Wakefield Poole considered “degrading,” which prompted him to develop Boys in the Sand (1971). Signature also released the film adaptation of the pulp frontier novel Song of the Loon, which was coproduced by Sayles and Sawyer under the corporate name Sawyer Productions.

Shan Sayles was extremely successful, and his endeavors proved that gay audiences were a viable market, hungry for positive films that expressed their experiences. Yet more than the films he produced, Sayles should be remembered for how his businesses provided space for local gay community formations. He was perhaps the first entrepreneur to conscientiously hire gay men to perform in, direct, write, and edit gay films. His expert advertising techniques propelled Continental’s theaters into the public view as open spaces of gay affirmation. Yet because of widespread homophobia, this visibility threatened the heterosexual status quo. Throughout the 1970s, Sayles fought First Amendment battles on both the local and the federal levels. In the struggles against arbitrary obscenity laws and unjustified raids, Sayles and his associates vigorously defended the right of LGBT people to produce and consume sex-affirmative material and to gather in public venues free of harassment.

In short, Shan Sayles should be remembered as a champion of LGBT public life. He passed away in Pacific Grove, California on December 21, 2016.

A version of this article previously appeared in Physique Pictorial. The author is grateful to Tom DeSimone for his informative discussions of this early period of gay film history.

Finley Freibert is a part-time senior lecturer in Comparative Humanities and Women’s Gender and Sexuality Studies at the U. of Louisville and an adjunct lecturer at the Kentucky College of Art and Design.