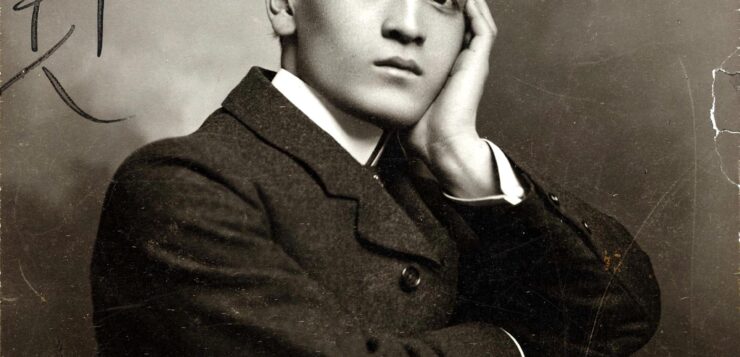

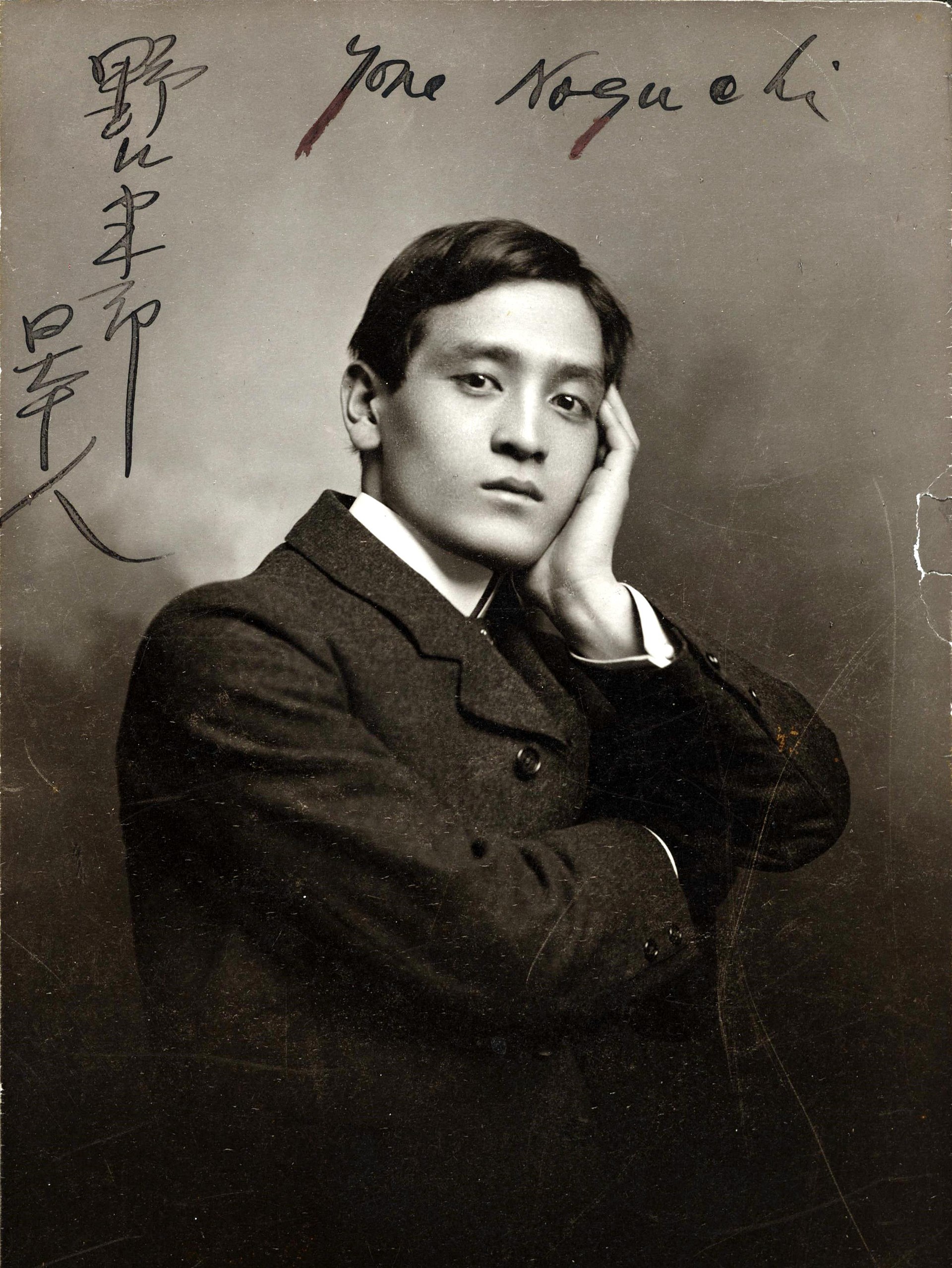

SAN FRANCISCO BAY remained hidden to outsiders for centuries because its entrance is narrow, and from the perspective of a ship at sea even that small opening appears to be filled by Alcatraz, as though the small island in the middle of the bay had been deliberately positioned to trick the eye and make the coast appear unbroken. And then there is the fog that shrouds the jagged rocks and obscures the swirling currents. Through that narrow opening in 1893 sailed the steamship Belgic carrying a seventeen-year-old Japanese poet named Yone Noguchi, a young man who would prove every bit as confounding as the landscape he was entering. In navigating his way across the continent for the next decade, Noguchi would be resourceful, passionate, studious and elusive. To further his writing career he would depend on the kindness of strangers, many of them lesbians and gay men, for whom he played the role of the exotic and seductive cipher, performing their Orientalist fantasies in order to gain what he needed.

Noguchi arrived during the narrow window between the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 and the anti-Japanese laws of the 1910s and 1920s. Japanese immigrants were exempted from some of the worst expressions of anti-Asian hate during this period, but California could still be far from welcoming. On his first evening in San Francisco, Noguchi wandered up Market Street, entranced by the streetlights and the tall buildings, the din of traffic, and the clang of the cable car bells. “I was suddenly struck by a hard hand from behind,” he later wrote, “and found a large, red-faced fellow, somewhat smiling in scorn.” The man sneered, “Hello, Jap!” and spat in Noguchi’s face.

He quickly discovered that his English could not be understood. Although he had studied the language for several years, his Japanese teachers “had not given me the right pronunciation of even one word.” With this language handicap, his employment options were few. He found a position as a houseboy for a Jewish family living at the corner of Van Ness Avenue and Sacramento Street, only a few blocks from where Alice B. Toklas was then growing up at Van Ness and O’Farrell. Hungry to speak his own language, Noguchi frequented the editorial offices of Sōkō Shimbun, the city’s Japanese daily, at first delivering newspapers for them but eventually working as a translator.

At the Japanese YMCA on Haight Street, he met Kosen Takahashi, an artist who worked as an illustrator for Shin Sekai, the Y’s newsletter, and the two men entered into a passionate—though perhaps lopsided—romance. To a mutual acquaintance Takahashi confessed that he had wooed Noguchi “as a boy do so for a girl,” and proclaimed: “Yone is my lover forever.” Together they began publishing an English-language literary journal titled The Twilight, which studiously avoided the drifting-cherry-blossoms and bashful-geisha racial tropes that Western readers so relished. The publication was short-lived. When Noguchi suddenly disappeared (on impulse he had decided to walk to Los Angeles but lost interest by the time he reached Palo Alto), Takahashi was frantic with worry. “I am nearly drowning with great Tear-flood to having been lost my dearest friend, Yone Noguchi,” he wrote in a letter that displayed his struggles with English, “an eloping lover who sudden deserted from me … leaving me with many sorrow and tears. Oh! where is my sweetheart?”

Cobbling together parttime jobs provided only a meager income and no time to improve his poetry, so Noguchi was intrigued when he learned of Joaquin Miller. The so-called “Poet of the Sierras” had established a bohemian colony in the Oakland hills called (and eccentrically spelled) The Hights. Miller lived in a small Victorian cottage overlooking the bay, but he had scattered one-room cabins around his property. These he made available to artists and writers in exchange for a few hours a week of manual labor around the compound. Noguchi climbed the steep hill to Miller’s cottage, unannounced but warmly welcomed. While Miller was so lecherous toward women that he was known among his friends as “the Goat,” he was clearly impressed by Noguchi’s appearance. He wrote of their first meeting that Yone must have followed the wandering path of a “Nippon butterfly” to Miller’s front door. He described the young man as a “beautiful Japanese flower,” the most lovely blossom he had ever seen “in the human flesh of either sex.” In an observation that meant something quite different in 1896 than it does today, Miller told a reporter for The San Francisco Chronicle when asked about Noguchi: “I like queer folks—the queer are always good. This boy is the right sort; he does just as he pleases.”

From his perch on The Hights looking back at the Golden Gate, Noguchi began to study American poetry closely. He fell in love with Poe and Whitman, dissecting their poems obsessively to learn how they worked. Joaquin Miller was a leading light of the San Francisco literary scene, and he introduced his young Japanese friend to all of the important regional writers. When Noguchi shyly began to share his poems with others, the response he received was cautiously encouraging. The poems were imaginative and strikingly original, but hard to parse—at times completely unintelligible. Lines such as “At shadeless noon, sunful-eyed,—the crazy, one-inch butterfly (dethroned angel?) roams about, her embodied shadow on the secret-chattering grass-tops in the sabre-light” left his readers baffled. Clearly he needed someone to help him channel his poetic thoughts into more comprehensible English, but in a way that would not erase the rich influence of Japanese haiku.

One of the first writers to give Noguchi encouragement was Adeline Knapp, the journalist whose messy breakup with her lover Charlotte Perkins Stetson (later Gilman) provided grist for the gossip mills in 1893. He was taken under the wings of Gelett Burgess and Porter Garnett, the editors of The Lark, San Francisco’s most prestigious literary journal. Launched at first as a humor magazine, The Lark appeared only briefly (1895–97), but, like England’s The Yellow Book, it has been acknowledged as an important publishing landmark because of the Zeitgeist it captured and the careers it launched. The editors were intrigued by Noguchi’s poems, which in Garnett’s estimation were “only slightly touched by incoherence.” They smoothed his English with skill and tact, but when the poems began to appear in the The Lark they garnered mixed reviews. In the San Francisco Examiner, the ever-irascible Ambrose Bierce used his regular column as an open letter to Noguchi: “I shall give myself the unhappiness to tell you that the estimable gentlemen and ladies having you in tow, O Brain-Boat-of-Down-the-River-Cascade-Going, are making an honorable fool of you. Your work is the most lamentable nonsense that ever kindled inextinguishable laughter on Olympus.”

With Burgess and Garnett’s assistance, Noguchi published two volumes of poetry, Seen & Unseen and The Voice of the Valley, and he prepared single-sheet poems that he sent to the leading literary figures of America and England. His poetry drew sincere praise from both Ezra Pound and William Butler Yeats, who hailed him as a master of the emerging Imagist movement. Most writers (Willa Cather among them) responded with somewhat puzzled encouragement, but from one novelist came a florid shower of praise in a letter whose envelope was marked “Private and Confidential”: “Dear friend who has come to me out of the Orient! Do you know that I have sent you many unwritten letters; many warm messages of love and sympathy? Some of these have reached you; some of these you must have heard—perhaps in a dream. … I was going to ask Joaquin to introduce us. I waited and called out to you listening for the echoing response. … [T]he Muse has at last brought us face to face and heart to heart. Now we must abide together.”

This geyser gush of adulation came from Charles Warren Stoddard in 1898. The novelist, who was then 55 years old, had taught at Notre Dame but was fired because of an inappropriate relationship with a student, and while at the time of his letter to Noguchi he was teaching English literature at Catholic University in Washington, D.C., his job there was hanging by a thread. He had been following Noguchi’s career from afar and had built up a rich erotic fantasy about him.

In his semi-autobiographical novel For the Pleasure of His Company (1903), Stoddard describes the life of a gay man trying to find his way in late 19th-century San Francisco. Since the days of the Gold Rush, San Francisco had been a place where people came to reinvent themselves, to try on different personas to see which one(s) felt right. But in a city that celebrated eccentrics, divas, and poseurs, Charley Stoddard felt depressingly average. It took trips to Hawaii and Tahiti in 1864 to allow him to spread his wings. There Stoddard became for the first time the exotic outsider himself, and with Polynesian culture’s more relaxed attitudes toward male-male sexual pleasure, he reveled in being the object of desire for many handsome young men. To Walt Whitman he wrote: “For the first time I act as my nature prompts me. It would not answer in America, as a general principle, not even in California where men are tolerably bold.”

Stoddard fictionalized his adventures in a book he titled South Seas Idylls (1873). Herman Melville had charted the course with his novels Typee and Omoo, but where Melville veiled his encounters so skillfully that literary scholars even today argue about how much homosexual activity he actually experienced with Pacific Islanders, Stoddard employed barely a palm frond to conceal his intimacies: “Again and again he would come with a delicious banana to the bed where I was lying, and insist upon my gorging myself, when I had but barely recovered from a late orgie of fruit, flesh, or fowl. He would mesmerize me into a most refreshing sleep with a prolonged and pleasing manipulation.” Only someone completely clueless about what two men do in bed could miss the allusion.

When he returned stateside, Stoddard attempted to replicate the life he had shared with the handsome men of the South Seas, but the closest he could come was a series of relationships with men who were much younger and working-class. He called each of these young men in turn “Kid” and insisted that they call him “Dad.” At the time that Noguchi’s exploratory letter reached him in Washington, D.C., Stoddard was distressed by the deterioration of his relationship with his latest Kid, a wastrel named Kenneth O’Connor. Stoddard had already known O’Connor slightly when the fifteen-year-old approached the famous novelist one day on the street and made it clear that he wanted to know him better. They withdrew to the ivy-covered brick house on M Street that Stoddard called “The Bungalow,” and he promptly fell in love with the “street-corner tough.” But Kenneth had now grown older, and he was cruising the streets of the nation’s capital on his own, bringing his tricks back to The Bungalow. For Stoddard it was “hellish torture.” Now this handsome Japanese poet from California might possibly be his new Kid, someone who was young, racially exotic, and clearly very talented. Here was the promise of the languid sensuality of the Pacific rim once again, now lapping at his own front door.

Yone Noguchi’s response was equally eager. He wrote that he had kissed Stoddard’s first letter upon receiving it, a missive that had arrived like “moonbeams.” He immediately matched Stoddard’s ardor: “I like you. I love you, I like to be some day in your study sitting all day by you indeed.” In the exchange of letters that followed, Noguchi made clear the dynamics of the relationship he was seeking. He wrote to Stoddard that he was only “a Japanese youth of no experience,” and he wanted to be the older man’s “most feminine dove.” After only four months of cross-country correspondence, having not even met Stoddard yet, Noguchi abased himself completely: “If you command me that I must be with you I will come to you—That’s all!—That’s all!” He sent Stoddard “juicy kisses.”

But how much of this passionate rhetoric was real, and how much is only fog and shoals? Noguchi had surely heard from Joaquin Miller that Stoddard was a homosexual (it was open knowledge in San Francisco) and the young man had by this time experienced the power that his Asian-otherness could wield in attracting people’s interest. Yet a sexual relationship with an older, more-established man was perhaps exactly what Noguchi was seeking, given the culture from which he had emerged.

For centuries, part of the samurai code of bushidō included an institution known as shudō (or nanshoku), a type of knight-squire arrangement in which an older man (nenja) became a mentor to a younger (chigo), a relationship that frequently included sex. During the Meiji period (1868–1912) the samurai were suppressed in an attempt to westernize Japanese culture, but as an unexpected result, shudō was taken up by Japanese schoolboys as a romanticized notion of virile manhood and noble conduct. In the popular tales known as chigo monogatari the stories often ended with the death of the young chigo through violence or suicide—after which it is revealed to his older lover that the boy was in reality an avatar of a supernatural being. The stories were a potent brew of sex and death and vindication that might appeal to any schoolboy with a flair for the dramatic, and this fascination with nenja/chigo sexual relationships was at its height during Noguchi’s adolescence. He almost certainly saw in Stoddard an older mentor who could guide him as a fledgling writer—and sex would be an expected part of the package.

In 1900, the two men finally met, and from his very first night at The Bungalow, Noguchi and Stoddard shared a bed (while Kenneth O’Connor slept on the divan downstairs). The two read together each evening in a single large armchair, their bodies entwined. Noguchi would always express his deep love for the man he called first “Charley” and then “Dad.” After his return to Japan, he repeatedly urged Stoddard to join him, promising to take care of the aging novelist in his declining years. Deep affection remained long after there was any prospect of Stoddard’s helping to boost Noguchi’s writing career.

There are two more strands that need to be added to this story. While staying briefly in New York City, Noguchi hired Léonie Gilmour as an editorial assistant to help him with a novel he was writing. In The American Diary of a Japanese Girl (1902), Noguchi took on the persona of a perceptive ingénue visiting the U.S. for the first time, filtering his personal observations through the voice of the female narrator. Sometime during the months they worked together on The Diary, the author and the editor began a sexual relationship, but when Gilmour later wrote to tell him she thought she might be pregnant with his child, Noguchi only scoffed at the announcement. He was uninterested in an entanglement, as he was by then engaged to a journalist for the Washington Post named Ethel Armes. For months the engagement to Armes was on again, off again. One of their problems was that Ethel’s sexuality was as unsettled as Noguchi’s. She cared deeply for Yone, but he was not quite the virile figure she craved. To her intimate friend Alice Wiggin she explained her dilemma: “Oh he is not big as I dream nor strong nor bravehearted nor practical nor—how could I say—protecting—if one could use that word—I feel so much that it is I who would have to be the husband—that is it—when I want to be the little one—and the wife.” It would be so much easier if two women could marry. “Really Alice if you were a man it would be ideal and I know I wouldn’t get into such a mess as I do with all of them. You’d manage me. (That’s what I want!).” In her letters she often addressed Alice as “my man.” Ethel broke off the engagement with Yone for good when she learned of Léonie’s pregnancy.

In 1904, Yone Noguchi decided to return to Japan. As his ship sailed out of the Golden Gate, he left behind a trail of entanglements. Léonie Gilmour was seven months pregnant and living in Los Angeles. Their son, Isamu, would grow up to be a world-renowned sculptor, his fame far outstripping that of his father. Ethel Armes had returned to her family in Birmingham, Alabama. She never married but published several books of local history. Charles Warren Stoddard retired to an actual bungalow in Monterey, California, where he died in 1909, within sight of the Pacific but with no Kid by his side.

In Japan, Noguchi was hailed as a major poet and a scholar of English literature, but in his absence the country had become extremely conservative. During the Russo-Japanese War (1904–05) militarism had seized control of Japanese society, and the schoolboy fantasy of nanshoku had morphed into the reality of violent gay youth gangs. As Furukawa Makoto writes in his exploration of the period: “The fashion for nanshoku led to the formation of groups of delinquent students, centered on homosexual relationships. These groups, with names like White Hakama Group and Blue Dragon Justice Group, would chase after bishōnen [beautiful boys], threaten them, assault them, and then enroll them as new members—all this in broad daylight, in public squares and streets.” The government began to crack down on homosexual activity of all kinds, applying a previously little-used sodomy statute from 1873. It is perhaps not surprising, then, that Yone Noguchi chose to marry his housekeeper and father three children with her. In all of his many published works in the years ahead, in both English and Japanese, Noguchi presented himself as strictly heterosexual.

It is difficult to dismiss a poet whose work drew praise from both Ezra Pound and William Butler Yeats, yet, after reading some of his early published efforts, it is equally difficult to disagree with Dore Ashton’s assessment that Noguchi’s initial literary success came about simply because he was “a beautiful Japanese boy who wrote quaint English.” Being that boy opened doors and gave him access to the tools he needed to make the most of his natural talent. If he had remained in Japan, if he had never transformed himself into an exotic object of desire, he might not have become such an accomplished poet. At a distance, his sexuality is too complex to label, but both men and women found him attractive, and the fluidity of his sexuality was part of the attraction. That first night on Market Street, when he discovered no one could understand his English, when a complete stranger struck him and spat in his face, Noguchi felt isolated and vulnerable. Soon enough, he learned that his good looks could be used as a shield—and even a sword—and he wielded them with the practiced skill of a samurai. The beautiful Nippon butterfly could also sting.

References

Austin, Roger, Genteel Pagan: The Double Life of Charles Warren Stoddard. Univ. of Massachusetts Press, 1991.

Marx, Edward, Yone Noguchi: The Stream of Fate. Botchan Books, 2019.

Sueyoshi, Amy. Queer Compulsions: Race, Nation, and Sexuality in the Affairs of Yone Noguchi. Univ. of Hawaii Press, 2012.

William Benemann is the author of Unruly Desires: American Sailors and Homosexualities in the Age of Sail, and Men in Eden: William Drummond Stewart and Same-Sex Desire in the Rocky Mountain Fur Trade.