Florine Stettheimer: Painting Poetry

The Jewish Museum, New York City

May 5–September 24, 2017

MAKE NO MISTAKE: in the first major U.S. exhibition in over twenty years devoted to this artist, we are treated to just how radical Florine Stettheimer’s paintings were. Her best work splits open the frenetic, exhilarating world she lived in with her frank, beautiful, and bewitching paintings, which are among the most eloquent and powerful social critiques of her time. Connoisseurs of camp will relish her originality.

In the past, Stettheimer has often been characterized, in the words of one interpreter, as a “lightweight feminine artist with a whimsical bent.” Stephen Brown, one of the organizers of this thought-provoking exhibit at the Jewish Museum in Manhattan, asserts that “This view is belied by her powerful thinking of portraiture and her astute adaptation of European vanguard ideas, most notably Symbolism, to uniquely American imagery.” However, when Brown positions Stettheimer as the “last” Symbolist, he does her a disservice, if only because assigning end points to artistic movements is an exercise in futility. More to the point, Stettheimer’s art has nothing to do with Symbolism; rather, her work is a devastating critique of modern life informed by a camp sensibility. Brown is uncomfortable with the open-endedness of Stettheimer’s urbane art, which resists categorization. I understand the drive that art historians have had to manufacture order, but these categories often reveal more about the interpreter than about a given artist’s work.

Stettheimer and her sisters were in Paris in 1910, attending the premier of the Ballets Russes’ production of L’après-midi d’un faune, featuring Vaslav Nijinsky’s notorious performance as the faun. Taking a contrarian point of view, Stettheimer saw the sexually explicit representations of the Russian dancer, which critics of the day called “lecherous” and “bestial,” as something beautiful and marvelous. She found his play-acting as engaging, as did her lesbian cousin Natalie Barney, whose Friday afternoon salon at 20 rue Jacob the Stettheimers certainly visited while abroad.

Florine Stettheimer was born in 1871 into a wealthy Jewish family in Rochester, New York. She was artistically gifted from an early age and studied at the Art Students League in New York City and then in Europe, where she was inspired by the Ballets Russes. She returned to New York in 1914. Her work must be seen in the context of the social and intellectual environment of early 20th- century Modernism and New York’s avant-garde. Her paintings trace the mass culture of her times from the Gilded Age to the Jazz Age, linking the cosmopolitan sensibilities of Europe and Manhattan. When Stettheimer made her New York debut in 1916 with a solo show at the prestigious Knoedler Gallery, it was a bust, garnering lukewarm reviews and no sales.

Ever resourceful, Florine, her two sisters, and their mother determined to showcase Florine’s talents by creating an elite salon that would, and did, attract many of the leading lights of the artistic vanguard: Charles Demuth, Marsden Hartley, Carl Van Vechten, and Virgil Thomson (all gay); Cecil Beaton, Georgia O’Keeffe, and Baron Adolph de Meyer and his wife Olga, a lesbian who was the god-daughter of Edward VII; writer Natalie Barney and artist Romaine Brooks, both lesbians; and Alfred Stieglitz, Marcel Duchamp, Gaston Lachaise, Marie Sterner, and Leo Stein (heterosexuals).

A thoroughly modern heterosexual woman and feminist, among her earliest and most scandalous pieces was Florine’s nude self-portrait with red hair (1915). In an astonishing rebuke to European painting, she challenged art historical tradition, spoofing Manet’s Olympia by painting her own aging body in a defiant demonstration of feminist autonomy: as the subject of her own gaze. In Family Portrait II (1933), she shows herself in her signature black pantsuit, which her definitive biographer, Barbara Bloemink, called “her artist’s uniform” to express her independence. In her utopian dystopias, none of the women depicted depend on men for their survival. Instead, she portrays women as the midwives of creativity.

Her larger paintings are orchestral in scope and bristle with biting commentary, revealing a wholly cosmopolitan attitude toward gender and sexuality that is thoroughly modern. Take, for example, the transgendered rendering of Nijinsky in Music (1920). His adornments include a prominent Adam’s apple, hairy underarms, and feminine dress with tantalizing cleavage, neatly nipped in the waist à la Scarlett O’Hara.

Stettheimer’s portrayals (all in 1923) of photographer Baron Adolph de Meyer, artist Louis Bouché, and Marcel Duchamp—and his female persona, Rrose Sélavy—are decidedly camp and fey. Taking a leaf from cousin Natalie’s gatherings, Florine’s open studio offered a natural mixture of friends with different sexual preferences that continued throughout Stettheimer’s life, until her death in 1944.

Florine didn’t storm the cathedrals of art; she painted them. Her landscapes are populated with family, friends, bohemians, and those who defy categorization. Her presence is vividly alive in her puns and jokes as she insightfully depicts her cast of characters with tongue-in-cheek affection. Her salon was remarkable among New York salons for its openness. It provided an environment where gays and bisexuals felt comfortable being themselves and mixing freely with her friends. Over the course of her lifetime, she met actors, dancers, artists, photographers, society types, and writers. Florine didn’t suffer fools gladly and could be particularly satirical and mocking when it came to social pretentions, and she enjoyed showing the ridiculous side of human desires.

Stettheimer was devoted to her art, loved to work, and put a lot of energy into getting it seen. She had outsized intelligence and a keen awareness of culture and politics. Her running commentary on the mass culture of her times takes a hilarious turn in Spring Sale at Bendel’s (1921), where she renders upper-class women far from the glittering pages of the society columns. Instead, she shows them trying on the latest fashions and fighting each other off as they snatch bargains out of each other’s claws. Everything is about spending and one-upmanship—not much has changed.

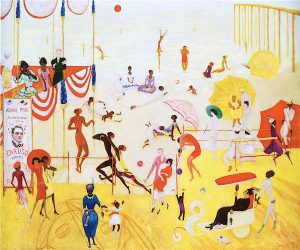

As a Jew, a woman, and an artist, Stettheimer’s progressive politics shone in Asbury Park South (1920). The painting is deceptive, with its brilliant yellow tones and trouble-free sense of movement as the black and white beachgoers intermingle on the New Jersey beach, and Florine is seen walking under a bright green parasol enjoying the festivities. This was at a time when Asbury Park was a segregated beach. Stettheimer has defiantly integrated the restricted area, desegregating it with members of her free-thinking inner circle, including Duchamp and writer Carl Van Vechten.

According to Barbara Bloemink, the sketches, drawings, and sculptures displayed in the exhibit demonstrate that Florine’s greatest passion was the theater and Ballets Russes rather than painting. This claim is defensible when one considers her theatrical collaboration with Gertrude Stein and Virgil Thomson on Four Saints in Three Acts (1934), one of the most audacious avant-garde experiments of the decade. Not to be missed in the show is a video clip of this production.

Stettheimer is remarkable as a woman and artist because, although a privileged white intellectual, she knew that she had both the freedom and responsibility to represent what she saw as the truth. Making art far from the safety and comfort of her family and home, she chose to engage with the most vexing social and political issues of her day: racism, sexism, class, and gender.

The Jewish Museum’s exhibit includes over fifty of Stettheimer’s smart, sexy, funny, campy commentaries on the foibles of human behavior to great advantage, and it proves what a radical artist she was. Her work never massages anyone’s ego, and it cuts through human bullshit with a piercing honesty that reveals her unsentimental view of art and life, creating a morally conscious art that’s as contemporary as anything being created today.

Cassandra Langer is a freelance writer based in New York City.