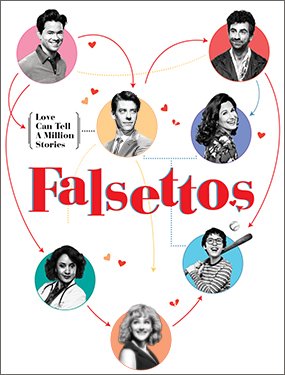

Falsettos

Falsettos

Music and Lyrics by William Finn

Lincoln Center Theater

Sept. 29, 2016–Jan. 8, 2017

WILLIAM FINN’S Falsettos, the AIDS-era musical now revived on Broadway, may be viewed by some as an odd period piece, by others as an operatic pastiche, a manipulative emotion-fest, or a stirring work of historical reconstruction. What may determine your response to the play—which shifts from 1979 to 1981 between two acts—is your willingness to believe in the musical comedy as a vehicle able to convey emotional truth rather than just cheap sentiment.

As in most operas, the dialog is entirely sung rather than spoken. The narrative traces the split of a married couple so that the husband can follow his newly realized gay orientation in the arms of a younger, less domesticated gay man. As drama, this might have been an unsparing account of that now bygone era when women emerged from the domestic prison, standard marital arrangements were reconfigured, and closeted homosexuals dropped the bourgeois disguise to find their true selves. But Finn chose to set his story at a critical time in gay history: the difference between 1979 and 1981 was a rupture in the gay world. It is through this shift from the world before AIDS to the world of AIDS that this musical—which is at once zany and tender, knowing and self-deprecating, naïve and lacerating—forces its audience to recalibrate its response.

Act One obsesses on its characters’ emotional conundrums: the marital split of Marvin and Trina; the sexual heat and bickering of Marvin and his lover Whizzer; Marvin’s strained relations with his ten-year-old son Jason; and Marvin’s psychiatrist Mendel falling in love with Trina. As a stand-alone work presented in 1981, this act was titled “March of the Falsettos.” Its quick-witted vocal repartee, with knowing asides and inside references to Big Apple urbanity and neurotic New York Jews, may once have seemed topical but now seems rather stereotypical—in a good way, if one doesn’t mind having ethnicity and religion reduced to loving caricature. In the opening number, “Four Jews in a Room Bitching,” the four male cast members sing and dance in Middle Eastern vaudevillian drag. They peel off their robes to contemporary dress; it has all been a parody, a way of getting our attention.

Finn’s lyrics can be witty, the melodies infectious, the rhyme schemes simple but emotionally sharp, as in Trina’s comical cri de coeur as the abandoned wife of a husband whose gay feelings came late, leaving her betrayed: “Men will be men…/ Let me turn on the gas./ I saw them in the den/ With Marvin grabbing Whizzer’s ass.” Trina’s song enumerates in frazzled crescendo her humiliations by a man who could not really love her. Now that her marriage has been exposed as a sham, she’s on the verge of nervous collapse: “Marvin was never mine./ He took his meetings in the boys’ latrine./ I used to cry./ He’d make a scene./ I’d rather die than dry clean/ Marvin’s wedding gown./ I’m breaking down./ I’m breaking down.” This may read flat on the page, but in the powerhouse performance of Broadway and TV veteran Stephanie J. Block, Trina takes on the vivid life of a woman at her wits’ end, her world thrown off its axis. She sings this snappy series of grievances with ever more manic, and comic, desperation, twisting her body into a pretzel, tearing at her apron, literally fit to be tied.

Ten-year old Jordan is one of those all-too-knowing nerdy kids whose emotional life hasn’t caught up with his intellectual powers. Failed by his “homo” father, who has left the family nest, Jordan’s withholding his love is the punishment that most pains Marvin. Marvin, played by Christian Borle (Broadway’s Something Rotten!; TV’s “Smash”), is the narcissist who wants it all—a “tight knit family” that can include his wife, lover, and child. Jordan’s acting out requires a psychiatrist, agree Trina and Marvin, but a simpler, more lasting solution occurs when Trina falls for Mendel and a new tight-knit family emerges as she and Mendel marry. Meanwhile, Marvin and Whizzer’s relationship ends on the rocks.

First presented Off-Broadway in 1990 as Falsettoland, Act Two shifts to 1981 and finds Jordan resisting his Jewish rite of passage, the bar mitzvah. Planning the celebration brings Marvin and Trina together in something close to cooperation. Suddenly, Whizzer re-enters Marvin’s life. There is also Dr. Charlotte and Cordelia—the wise and loving “lesbians next door.” This act hinges at first on whether Jordan will thwart his parents, thumbing his thirteen-year-old nose at religious tradition, or whether Marvin, Trina, and Mendel will prevail. The latter provides Jordan with his professional reassurance that “Everyone Hates His Parents.”

None of this feels like a plot element for deepening drama, and the bar mitzvah’s import in Jewish lore—as opposed to signifying middle-class social indulgence—is never given a hearing. But just as one fears that Act Two may simply continue satirizing the dysfunctional contemporary family, Finn offers a maturing Marvin in the gorgeous ballad, “What More Can I Say?” Borle sings this tender lullaby marvelously well, while Whizzer (Andrew Rannells) sleeps naked beside him. Almost more whispered than sung, the song helps shift things into fresh territory as Dr. Charlotte alerts her friends that “Something Bad Is Happening.” While the “something” is never named, the audience knows it to be AIDS. How it will impact these characters is best left unrevealed. Rest assured, there is loss. But grave illness also propels the bar mitzvah boy to a generous act of maturity.

The ending might even have satisfied the gimlet-eyed Oscar Wilde, who famously said: “One must have a heart of stone to read the death of Little Nell without laughing.” The trouble with the sentimentalist, as Wilde saw it, is that he “desires to have the luxury of an emotion without paying for it.” By 1990, Finn’s audience had paid for it. With restraint, the single death in Falsettos occurs off-stage, but it stands for so many others in that dreadful era of Ronnie and Nancy, and ever since. It earns our tears.

Allen Ellenzweig is the author of a forthcoming book on photographer George Platt Lynes.