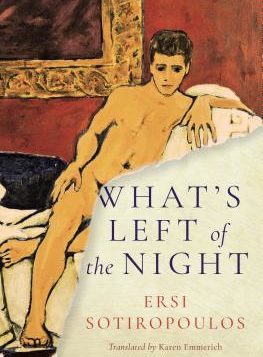

What’s Left of The Night

What’s Left of The Night

by Ersi Sotiropoulos

Translated by Karen Emmerich

New Vessel Press. 257 pages, $16.95

THIS IMAGINATIVE NOVEL tells the story of the early years of the poet C. P. Cavafy when he was simply Constantine. Set during three days in Paris in 1897 while Cavafy is traveling with his older brother, it shows him slowly discovering his voice and subject matter while exploring the city and remembering its history.

Much of the action takes place in Constantine’s mind as he wanders Paris alone and with his brother John or with a fellow Alexandrian, Nikos Mardaras, secretary to the French poet Jean Moreas.

The novel is filled with literary references. In his first conversation with the brothers, Mardaras mentions Marcel Proust, whose “name was unfamiliar to” Constantine, and also that of Anatole France. Constantine analyzes Baudelaire’s poem “The Albatross,” seeing the bird as a symbol for “the poet’s position in contemporary society,” but also wondering: “didn’t everyone long for the infinite?” Walking through the city, he mentally works on one of his poems, repeating lines from what will become “The City.”

The relationship between Constantine and his brother John is shown to be rather complex. John is also a poet, and the two make suggestions about each other’s work. Constantine reproaches himself for a quip he made about there not being “room for two poets in one family,” and later mentions a gift John has bought for a servant in front of Mardaras, making John visibly uncomfortable. John has his revenge in a letter that quotes John Donne’s “No man is an island,” leading the nervous Constantine to fear the worst.

Some elements of the novel are perplexing. Early on, Constantine encounters a mysterious young peasant boy with bruises on his legs. The boy makes brief appearances throughout. Another character mentions his magical facility with pigeons. Toward the end, Constantine sees the boy in a cage, “hands tied behind his back, a kerchief over his eyes.” Men roughly shove Constantine around, menacingly making him repeat “eggs don’t have skin.” It is hard to understand what the boy might represent, or the meaning behind this bizarre episode.

The last chapter is also unusual. Throughout the book, Mardaras has dropped hints about “the Ark,” a secretive club on the city’s outskirts that is “a den of pleasure.” Constantine finally accompanies Mardaras to the Ark, and his experience is almost hallucinatory as he watches two women, “the queen and goddess of hysteria,” reacting to the effects of a magnet and a ringing sound. This is also where he encounters the boy again. Later, a guest takes him elsewhere to secretly observe two men engaging in a strange, unhygienic fetish. It is a final night that Constantine will never forget.

Karen Emmerich does a wonderful job translating the original Greek, with an English that flows easily, while keeping the feel of poetry. A well-researched, sympathetic novel, it should inspire readers to discover or rediscover Cavafy’s poetry.

Charles Green is a writer based in Annapolis, Maryland.