PROVING HERSELF equally adept at fiction and nonfiction, Sarah Schulman has been a prolific writer of novels, plays, and books of political history. Her most recent book is an expansive history of the crucial years of ACT UP (the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power), which is now regarded as one of the most important organizations in the annals of American activism.

At just over 700 pages, Let the Record Show: A Political History of ACT UP New York, 1987–1993 (Farrar, Straus and Giroux) grew out of the 188 interviews that Schulman and Jim Hubbard conducted for the ACT UP Oral History Project, which is available on-line as a public resource for researchers. Based on additional interviews and firsthand research, Schulman has produced an exhaustive chronicle of ACT UP’s origins and its rapid mobilization of human resources to achieve a level of visibility and success that have made the group legendary.

Schulman spoke to me by phone from her New York apartment in early May. — MH

Matthew Hays: There have been a number of histories of ACT UP, including Jim Hubbard’s 2006 documentary United in Anger: A History of ACT UP, which you and Jim produced. What prompted you to write the new book at this time?

Sarah Schulman: I really didn’t want to write it. I wanted someone else to do it. When Jim and I first started the ACT UP Oral History Project in 2001, it was because the Internet revolution had happened, and ACT UP had sort of been lost in that, because none of our files were digitized at the time. So we just disappeared. We created all of this data, and the idea was that other people would interpret it. Over fourteen million people have visited the site. But people were missing a lot of what was there, and we were hoping that someone would write a book. We sent some people tapes of interviews and urged them to do it, but no one did. Then, when the misrepresentations about ACT UP started, it felt like a state of emergency, so I felt I had to do it. It took about three years.

MH: What were some of the misrepresentations you felt you needed to change?

SS: Well, according to Andrew Sullivan in The New York Times, the trajectory of AIDS was over in 1996. And then there’s this idea that change is made by historic individuals, which is false. In the U.S., change has been made by coalitions. This very divisive and inaccurate story that was being carved out was so detrimental to contemporary movements, because movements really need to understand that radical democracy and broad coalitions are what allow for paradigm shifts.

MH: I think many people still think of ACT UP as mostly comprised of white gay men.

SS: Well, it largely was white gay men. What I’m trying to point out is that it was predominantly white and male, but not exclusively. And that’s a very significant difference. Because when women and people of color participate, they have a huge influence, particularly, at that time. What I’m trying to counter is this idea of ACT UP as a discrete movement, when in fact all political movements are influenced by previous movements. Women and people of color came to ACT UP with a lot of previous movement experience that white gay men simply didn’t have. And they brought a lot of theory and practice and radical analysis to the movement—things like patient-centered politics and nonviolent civil disobedience. So it’s important to understand who these people were and what their contribution was. Also, Latino participation was quite significant.

This does not take away from other people’s contributions. The reason the movement was successful is because so many things were happening at once. If you just isolate one element and not show the dynamism of the complex movement behind it, you’ll never understand how it was able to function. That’s why I wanted that to be clear.

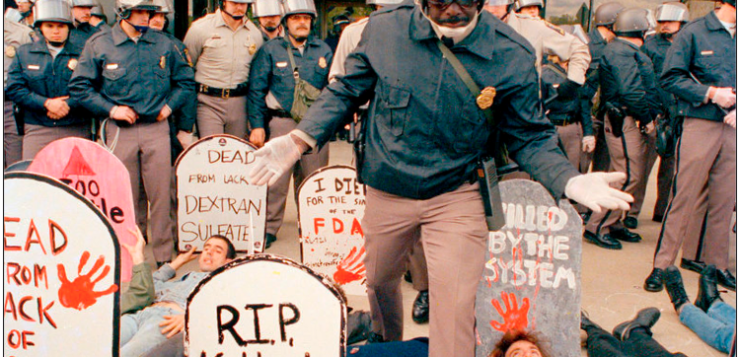

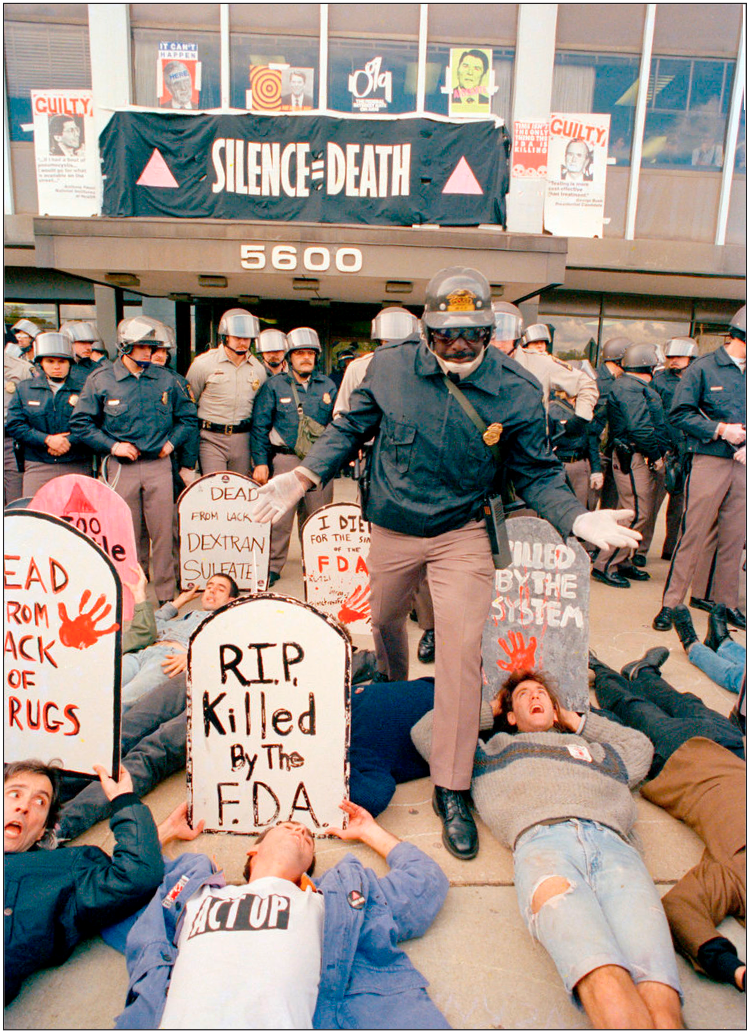

MH: You write about ACT UP’s headline-grabbing protests. Which one of them do you remember as the most outrageous?

SS: Probably the Day of Desperation at the start of the first Gulf War, which was the occupation of Grand Central Station. Thousands of us filled the entire hall. The slogan was “Fight AIDS, Not Arabs.” It was so gratifying years later when Jim Hubbard and I brought his film United in Anger to Palestine, Abu Dhabi, and Lebanon, and Arab audiences were able to hear that chant.

MH: ACT UP’s influences have been so varied and profound, but what do you see as its most important legacy?

SS: ACT UP’s greatest achievement in terms of direct lives saved was the four-year campaign to change the government’s official definition of AIDS to include symptoms that only HIV-positive women experienced. Without that change, women died of AIDS but never received an official diagnosis. That meant that they could not get benefits like home care or disability, but even more importantly, they could not qualify for experimental drug trials and compassionate access. Once women were allowed into trials, drugs could then be tested on women, which impacted their development, dosages, etc., toward the most effective medication for women with HIV. Today, every woman in the world who takes an anti-HIV medication has benefitted from that campaign.

MH: Some LGBT people seemed to regard the fight for same-sex marriage as some kind of final frontier, like our struggle for rights is all settled. What is your view of the current LGBT movement?

SS: As I say in the book, the reason that there was a discrete Gay Liberation Movement in the first place is because we were excluded by other progressive movements. Although queer people were in the leadership of every movement for progressive change, we had to be closeted or risk expulsion. Today, things have change dramatically. The leadership of all progressive movements in 2021— Black Lives Matter, the Dream Defenders, Palestine Solidarity, etc.—have openly queer and trans people in leadership positions. The LGBT movement had finally been allowed to integrate with integrity into the whole coalition for change.

MH: I had always felt that lesbian separatism ended as a result of the AIDS crisis. But you actually call out gay male separatism as something that existed at that time.

SS: Well, lesbian separatism is a very specific ideology that was connected to a kind of back-to-the-land movement in the 1970s and ’80s. Women were trying to get away from men controlling them. It has its own history. The term has been overused in ways that are not accurate.

But gay male separatism was really an economically constructed phenomenon. Gay men were a highly oppressed community at this time, and it’s hard for younger people to understand that, because things have changed a lot. At the time of AIDS, not only was gay sex illegal, but there was no antidiscrimination protection, even in New York City, so you could be kicked out of an apartment or told to leave a restaurant for being gay. I think a lot of gay men resented that they could not access the full rights and privileges of men. They tried different strategies to deal with that. Some were in the closet, some were quite misogynist.

But one of the things that ACT UP changed was that, although women didn’t have money, they had an incredible history of resistance and radical thinking. I talk about the idea of “no business as usual.” In order to be in ACT UP, you had to oppose The New York Times, science, the police, the art world—any institution that could help you professionally. There had to be a kind of recognition that certain kinds of ambition didn’t make any sense, and that these institutions needed to be opposed. And that internal revolution allowed men to see what women could bring to the movement. And they brought a lot to the movement. I think it transformed a lot of relationships.

MH: I’ve noticed that some of my students seem to have a nostalgia about the period you write about. “You were all galvanized and fighting mad,” they’ll tell me. What do you say to young people when they romanticize this time?

SS: The purpose of this book, and of our film United in Anger, is to encourage and help people today build activist movements that are effective. We see you and your desire and need for change. ACT UP is one example proving that change is possible no matter who you are. But you need focus, commitment, and flexibility.

MH: You end the book on a very personal note, as you go to a healthcare facility to have blood drawn, and find a connection with the nurse, who is finding a vein in your arm to stick a needle into. That passage, about shared memory, is intensely moving.

SS: There are a lot of women out there in their sixties who are veterans of the AIDS crisis in lots of different ways. That one of turned out to be a patient, me, and the other turned out to be a nurse, and we were sitting there talking about this experience we’ve shared. This is what I called the enduring relationship of AIDS, that those of us who went through the worst years—we bonded in a certain way. And I feel that with ACT UP. People who really disagree with each other politically then and now are still very bonded.

I know some people were worried about this book, but now that the book is out, they see that it’s very fair, and that I do give everybody credit for the work that they did. But I want all that credit to be spread around. I do show what people with the most access did, and what they accomplished. I talked to 140 people for the book so that readers could get an idea what a movement really looks like.

MH: Much of the book was very emotional to read. Sometimes that can be cathartic, but what about the emotional toll of writing such a book?

SS: Hard to say. From my beginnings as a reporter in the early 1980s—covering the closing of the bathhouses, pediatric AIDS, women with AIDS, and homeless people with AIDS—I have never stopped reporting on and creating work about the crisis and its consequences. So it is not like I had to suddenly stop life and look back. This work has consistently informed me about the moral imperative of hearing what people have to say about their own experiences at every level of society.

MH: You manage to make the book both intensely personal and political, but in the end you’re most interested in the organizing aspect, correct?

SS: There have been books about a number of different aspects of ACT UP, but this one is about the politics: what did they do, and how did they do it, and how can people today get something out of that information? What is direct action and how do you organize it? What is radical democracy? Today there’s so much emphasis on punitive conformity, and that does not work in political movements. The best movements are big-tent movements, with very simple principles of unity. ACT UP’s only principle of unity was direct action to end the AIDS epidemic. If you had an idea and I didn’t think it was good, I wouldn’t do it; I’d go work on my own idea. And that’s a healthy movement.

MH: So, some people were worried about what was in this book—what were they concerned about?

SS: Yes, and it was so sexist: “She’s gonna bitch slap us!” But now that the word is out, people can see that it’s fair. I think it’s a book that can reunite ACT UP. Because a lot of the stories about ACT UP have been very divisive. We’re all getting older, and people are dying, and we want to feel good about each other. We did something wonderful together. And we know that movements can be successful. We have that knowledge. That’s very important.

Matthew Hays, a regular contributor to this magazine, was a member of ACT UP NY in 1988 and currently teaches film studies and journalism at Condordia University in Montreal.