NO ISSUE on “the Heartland” would be complete without an article on Chicago, undoubtedly the beating heart—or is it the brain?—of this vast expanse. With this realization, I immediately thought of John D’Emilio as the logical person to contact for a targeted tutorial on Chicago’s LGBT history and culture. A longtime contributor to this magazine—on topics ranging from activist Frank Kameny to the fight for marriage equality and LGBT Brooklyn—D’Emilio is a professor emeritus of history and of women’s and gender studies at the University of Illinois at Chicago, where he taught for many years.

D’Emilio was inducted into the Chicago LGBT Hall of Fame in recognition of his many contributions to gay life in the city. In addition to his scholarly work, he has been an activist in both city and university affairs and recently served on the board of directors of the Gerber/Hart Library (discussed below). His scholarly work includes the recently published book Queer Legacies: Stories from Chicago’s LGBTQ Archives (Univ. of Chicago Press, 2020). His forthcoming memoir, Memories of a Gay Catholic Boyhood: Coming of Age in the Sixties, will be published next August by Duke University Press.

This interview was conducted in writing in late August based on a set of questions that I submitted to Prof. D’Emilio.

— G&LR Editor

The Gay & Lesbian Review: Broadly speaking, what was going on in Chicago, culturally and/or politically, in the pre-Stonewall era?

John D’Emilio: Evidence abounds that as early as the 1920s and ’30s, Chicago was the setting for vibrant LGBT communities. On Chicago’s South Side, for instance, where African-Americans migrating from the South settled in large numbers, the Chicago Defender reported frequently on drag performers at a number of popular clubs. The Cabin Inn, a gay bar, was described by the Defender as “Chicago’s oddest night spot.” Black female singers living and performing in Chicago, like Ma Rainey, sang songs with overtly lesbian and gay themes. In Towertown, a nearby North Side neighborhood with a bohemian flavor, a largely white gay male subculture of bars and cruising strips was well enough developed that it provided the tipping point for Alfred Kinsey’s research on male sexuality. Kinsey made half a dozen trips to Chicago in 1939, and the interviews he conducted with gay men there helped provide the inspiration for what became his historic study, Sexual Behavior in the Human Male, published in 1948.

G&LR: Did the Lavender Scare era of the 1950s have an impact on the growing openness of gay life in these earlier decades?

JD: Sadly, it did. Robert McCormick, the owner and publisher of The Chicago Tribune, was a very conservative Republican. When the Congressional investigation exposing the employment of homosexuals in the federal government began in 1950, McCormick gave it high-profile coverage. His purpose was to discredit the Democrats who controlled Congress and the White House in the 1930s and ’40s, who had vastly expanded the federal government by enacting a range of social programs. For McCormick, the revelation that “moral misfits” were employed by the federal government provided a compelling rationale for attacking what he perceived as a liberal federal bureaucracy. The Tribune published dozens of articles with headlines featuring words like “perverts,” “degenerates,” and “depravity.”

The tone set by the Lavender Scare also provided justification for police harassment, which was intense during the 1950s and ’60s. The structure of Chicago’s political machine, over which Richard Daley ruled from the mid-1950s into the 1970s, gave the police extensive freedom to raid bars, entrap men cruising in public parks and restrooms, and demand payoffs from bar owners. The city’s newspapers publicized the bar raids and mass arrests, sometimes printing the names of individuals who were arrested.

G&LR: How did Chicago respond to the Gay Liberation era after the Stonewall Riots in New York?

JD: Because of the intensity of oppression in those post-World-War-II decades, Chicago not surprisingly was one of the cities that saw the appearance of “homophile” activism in the 1950s and ’60s. While this early movement activism wasn’t as deeply rooted in Chicago as it was in New York or San Francisco, Chicago did have chapters of the Daughters of Bilitis and the Mattachine Society. Picking up on the new directions that the Black freedom struggle was taking, in 1966 Mattachine Midwest, as the group named itself, used the phrase “Gay Power” in its newsletter—to my knowledge, the first time that phrase was ever used in print. And in the summer of 1968, Chicago’s activists hosted a national conference of homophile organizations, where the slogan “Gay Is Good” was adopted by movement leaders.

So, Chicago was ready to be ignited by the Stonewall Uprising, and before the end of 1969, gay liberation groups were forming in the city. In June 1970, Chicago was one of only three cities that commemorated Stonewall with a public demonstration, which attracted of several hundred people. Soon it was producing newspapers like Lavender Woman and Gay Crusader. Chicago had one of the earliest trans activist organizations, the Transvestite Legal Committee, formed after Chicago police killed a Black transwoman. Chicago opened its first community center in 1971. And Chicago was often the city where activists from around the country met to plan national campaigns, such as the effort to be included in the 1972 Democratic National Convention’s platform and the annual lesbian writers’ conferences that began in 1974.

G&LR: Who were some key figures in the history of Chicago activism?

JD: There have been so many, more than I could possibly discuss. But let me identify a few. There was Valerie Taylor, one of my favorite figures in LGBT history. In the 1950s and early 1960s, she took the lesbian pulp genre and made it a vehicle for publishing a series of lesbian novels that presented women-loving-women in a humane and positive way. In the 1960s, she was active in Mattachine Midwest, and she was the keynote speaker at the first of the national lesbian writers’ conferences held in Chicago.

Then there are Bill Kelley and Vernita Gray, both of whom appeared on the scene in the 1960s and became fixtures of Chicago’s LGBT activism for the next several decades. Kelley, who joined Mattachine Midwest in the 1950s, became a lawyer and a key player in the various coalitions that formed over the years in the effort to win passage of a sexual orientation non-discrimination bill. Gray learned about Stonewall and gay liberation when she attended the Woodstock Festival in the summer of 1969. When she returned to Chicago, she helped form gay and lesbian liberation groups on the South Side, and over the years she was a deeply loved, inspiring public speaker who brought her Black and lesbian identities into the heart of Chicago’s queer activism.

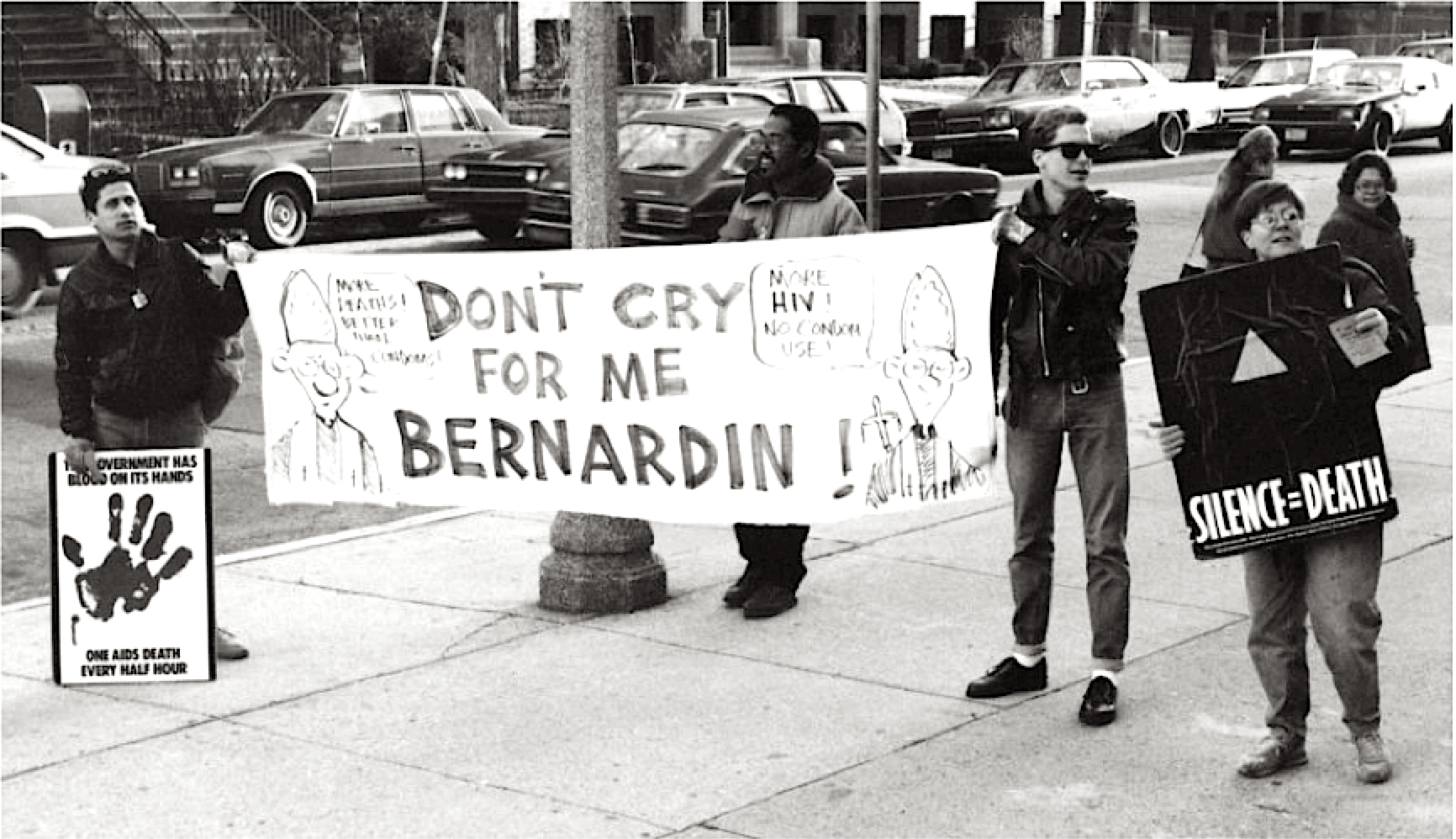

Finally, I’ll mention Danny Sotomayor. An activist in Chicago’s ACT UP group in the late 1980s, he was also an artist who used his skills to create a series of uncompromising political cartoons that lacerated political figures like Presidents Reagan and [George H. W.] Bush and Republican Senator Jesse Helms for their homophobia and their failure to address the toll of the AIDS crisis. His cartoons reached a very wide audience, as they were carried by LGBT newspapers in many cities.

G&LR: How did Chicago come to have such a large and well-organized gay ghetto that a neighborhood could be named “Boystown”?

JD: I would say that the naming of Boystown says less about its uniqueness as an urban gay male ghetto and more about the workings of Chicago’s political machine. As with many other cities, the places associated with LGBT life in Chicago shifted over time. The first gay bar did not open in the North Side Lakeview neighborhood until 1975. Because of urban redevelopment, bars were shutting down in other parts of the city, and more and more opened in Lakeview during the late ’70s and into the ’80s. When the second Richard Daley was elected mayor in 1989, he saw the cultivation of gays as one of his goals. He supported the creation of a city-sponsored Gay and Lesbian Hall of Fame, promised support for an LGBT community center in Lakeview and, in 1998, endorsed the naming of the Halsted Street strip and surrounding area as “Boystown.” An annual street festival on Halsted Street brought masses of folks to the neighborhood for several days in the summer. While “Boystown” speaks to the inclusion of gays in the mainstream liberal political, cultural, and social discourse of the 1990s, it has also had exclusionary effects, as the neighborhood was mostly associated with white middle class gay men.

G&LR: How and when was the famous Gerber/Hart Library and Archives founded, and what role has it played in LGBT life?

JD: Gerber/Hart was the outcome of two different projects. Around 1980, a group of community members came together to form a free lending library. At that time, buying an LGBT book in a bookstore or borrowing one from a public library branch was a form of coming out, and a majority of LGBT people were not prepared to do that yet. The lending library was a way of making available to anyone in the community the vibrant literature, both fiction and nonfiction, that had exploded into print in the 1970s. Meanwhile, Gregory Sprague, a graduate student at the University of Chicago who was working on a dissertation on gay history, had formed a Chicago LGBT history project with a few others. In 1981, these two initiatives came together to form the Gerber/Hart Library and Archives.

For most of its forty-year history, Gerber/Hart has been a completely volunteer-run organization. While the lending library still exists, over time the focus of Gerber/Hart has shifted, and it functions much more as an archive, museum, and cultural center. Its collections have played a key part in the writing of a number of recent books: Katie Batza’s Before AIDS, on the history of gay healthcare activism in the 1970s; Timothy Stewart-Winter’s Queer Clout, which traces the growth of activism in Chicago from the 1950s to the 1990s; and Rebecca Makkai’s The Great Believers, a compelling bestselling novel about the AIDS epidemic that she sets in Chicago. My own recent book, Queer Legacies, draws entirely on the collections in Gerber/Hart’s archives to create, through a series of separate stories, a collective portrait of LGBT social life, culture, and activism from the 1950s into the 21st century.

For most of its forty-year history, Gerber/Hart has been a completely volunteer-run organization. While the lending library still exists, over time the focus of Gerber/Hart has shifted, and it functions much more as an archive, museum, and cultural center. Its collections have played a key part in the writing of a number of recent books: Katie Batza’s Before AIDS, on the history of gay healthcare activism in the 1970s; Timothy Stewart-Winter’s Queer Clout, which traces the growth of activism in Chicago from the 1950s to the 1990s; and Rebecca Makkai’s The Great Believers, a compelling bestselling novel about the AIDS epidemic that she sets in Chicago. My own recent book, Queer Legacies, draws entirely on the collections in Gerber/Hart’s archives to create, through a series of separate stories, a collective portrait of LGBT social life, culture, and activism from the 1950s into the 21st century.

In recent years, Gerber/Hart has been mounting wonderful exhibits that display our history across a range of topics, generations, and constituencies. Prodded by the pandemic, it has expanded its website content significantly in the last two years so that much material is now available for viewing whether you’re in Chicago or not.

G&LR: You’ve done a good bit of research at Gerber/Hart, and your recent book, Queer Legacies, was based entirely on research there. Do you reach any general conclusions about gay life in the city based on this work? Are there any unique features to Chicago’s history, or contributions to the national story?

JD: Interestingly, in the writing of U.S. history, Chicago often serves as the representative, or paradigmatic, city. Studies of such varied topics as immigration, union organizing, urban reform, and the Great Migration will use Chicago as their case study. In terms of LGBT history, that has not been the case. New York, San Francisco, and Los Angeles have each been seen as more illustrative of the broad sweep of our history. And yet, Chicago’s queer past is so rich and so varied, as well as extending far back in time, that it could easily serve as an exemplar for outlining the broad sweep of the LGBT past. So, rather than single Chicago out for its uniqueness, I would hold it forth as potentially the best model for understanding how LGBT identities, communities, and movement activism have developed and evolved over the past several generations.

Discussion1 Comment

The Mattachine Society was a gay rights organization, not an LGBTQAI+++ organization. All gay rights organizations were for same-sex rights. There were transvestite organizations throughout history, but it was a niche group lurking around drag shows. Gay bars were a place female impersonators could go out in public in drag.

What are transgender rights? They are not same-sex rights. The 1993 March on Washington was the LGB movement we were fighting for. Lesbians and gay men united to fight AIDS even though AIDS only affected gay men at the time with zero political or social representation. If lesbians didn’t stand up for gay men, no one would.

Bisexual was added to the gay rights movement because they were facing the same threats to their lives as gay people. Accusations of gay activities or a gay relationship meant you lost your job, your career, your family, your children. Gay people lost their children on grounds of “moral terpetude”.

Gay people never fought for transgender rights. We fought for medical care for AIDS patients and same-sex rights. We never fought to change sex or any fantasy of “gender choice” or sex change mythology. The LGB movement was hijacked by the billionaires invested in the exploration of transhumanism. This has nothing to do with same-sex rights, same-sex relationships or the gay movement.

Gay people are homosexual. They love their own sex and gender. Men who say they are transgender or transsexuals are straight men who are attracted to women, excite themselves wearing women’s clothes and wearing the costume of woman in public. A woman is an adult human female. All lesbians are born women who love women. No lesbian is attracted to a man in a woman’s costume. No gay man is attracted to a man in a woman’s costume.

It’s time for the LGB movement to stand up to these lies for the sake of gay history and the gay movement.

I have no hatred toward female impersonators. I’m simply stating the position of lesbians which seems to always be ignored in the transgender and gay male conversations.