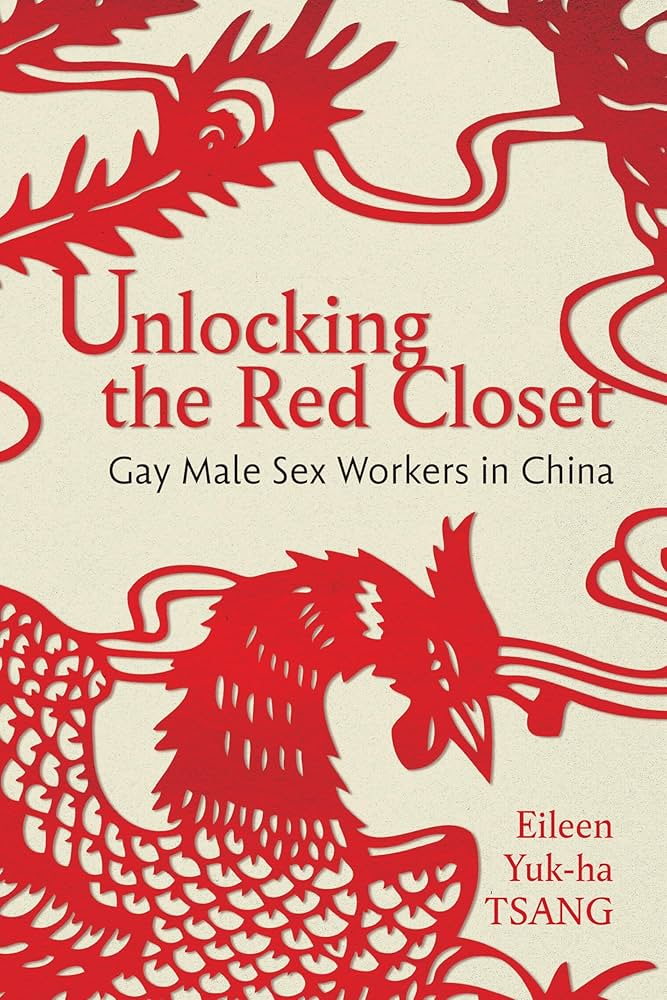

UNLOCKING THE RED CLOSET

UNLOCKING THE RED CLOSET

Gay Male Sex Workers in China

by Eileen Yuk-Ha Tsang

NYU Press. 233 pages, $30.

THERE’S NOTHING quite like coming out to your parents in a village in China. It’s painful enough most everywhere, but in rural China, you’re likely to be kicked out not only of the house, but also of the village. Fathers weep, mothers slap you, because what you are will cause your family to lose face. Saving face demands that you provide your parents with a grandchild. Not doing so is seen as a failure that goes against Confucian values. So the best you can do is move to a city and become a prostitute. But

That, at least, is the trajectory of the young men interviewed by sociologist Eileen Tsang in her new book about gay male sex workers in the city of Tianjin, located some 100 miles southeast of Beijing. In Tianjin, Tsang gets a job as a bartender at a gay nightclub she calls Pistachio to protect the real life model. Pistachio is very popular. It has rooms and suites upstairs where male sex workers can retire with their clients, floor shows that include everything from drag to Chinese opera, and even straight female customers seeking love and companionship. Everyone onstage is aware that the clock is ticking, that one can do this job for only a limited time. The sex workers go to Thailand and Japan for face lifts and nose jobs and anything else that will achieve the look their clients desire. Muscular gym bodies are in demand, as are certain skin colors (tanned if you want the butch, countrified look, creamy white if you prefer “soft masculinity”). The golden rule among sex workers is that you must never fall in love with a client—although, at the same time, the young refugees from the countryside are all looking for the sugar daddy who will fund their acquisition of all the accoutrements of a modern urban homosexual, a goal that may seem meretricious to the Western reader fed up with consumerism but that is not questioned in places like Pistachio. Ironically, it is working at Pistachio, negotiating payments, dealing with what the client wants, that ends up teaching the sex workers what they need to know when, after they grow too old to attract customers, many of them become what is called “livestreamers”—performers on one of the vast shopping networks selling facial creams, skin toners, and cosmetics online. Some of them get rich doing this—and as Mao’s successor Deng Xiao Ping famously proclaimed: “To get rich is glorious!”

To get rich is also arduous, and what’s so remarkable about the young men Tsang interviewed and in some cases befriended is how little self-pity there is in their stories. They don’t want sex work made legal because then the government would tax them. Nor do they want to tell their parents what they do. So they lie to everyone. Sometimes they do drugs. “Social death” is what Tsang calls it. “Necropolitics” (deciding which groups should live and which should die) is the word for what the government is doing through its policy of neglect. Transgender people are even more disdained; there’s not even a Chinese character for this word. Scorned by police, ignored by the government, and abused by their partners, they are forced to rely on one another. As for the gay male sex workers, most do not want to marry a village girl and wreck her life in order to please their parents; so they sometimes make an arrangement with a lesbian and give their parents the wedding, if not the grandchild, that they wanted. Unfortunately, some of them do still marry the village girl.

Unlocking the Red Closet is, like other books on this subject, a mix of sociological analysis and transcripts of the subjects’ interviews. There is mercifully little jargon, and the monologs are highly theatrical. And they are what make the book. There is a remarkable matter-of-factness to Chinese expressions that can be brutal to the point of being camp. For instance, a woman in her thirties who hasn’t married is referred to simply as a “leftover lady.” Two such women provide the best monologs in the book. One client tells Tsang, speaking of the rent boys: “I know that when they are through having sex with me, they go right into the bathroom and spit.” No matter, she goes on hiring them. “I am called the old ox who chews young grass.” As for her view of them: “These young boys are such terrible actors. I tell them to kiss me and I can tell that they are reluctant. I know those boys want to vomit in the washroom after I leave, and they only do it for the money.” She’s right. Her boy toy eventually has to sever ties with her because “I only wanted to get paid for my time. I would prefer she find another old Chinese woman to dance with and kiss. Finally, I had to delete her from WeChat and cut ties with her.”

The odd thing about the conclusion of this generous and empathetic book is that Tsang seems to be suggesting that, given the disdain in which same-sexers are held, these rural gay men who want to live a better, more honest life might be better off if they just skipped the sex worker phase and became livestreamers. Selling cosmetics to a huge following online may be the solution to the problem of gay social death in China—given the widespread belief on the part of the government and much of the general population that homosexuals cannot be part of the Chinese Dream.

Andrew Holleran is the author, most recently, of the novel The Kingdom of Sand.