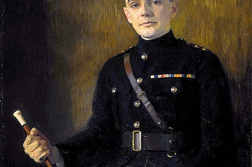

RADCLYFFE HALL’S The Well of Loneliness is the canonical lesbian novel that many people think they know; in some sense, it has become a part of queer folk culture. As the tragic story of a female “invert,” in the language of the time, the novel itself has been dramatically persecuted. Attacked in several courtrooms in 1928–29 for daring to suggest that gender “inversion” and sexual “perversion” should be tolerated, it has been attacked since 1970 by Second Wave feminist critics for its essentialist and patriarchal world-view.

And yet, like the martyred writer Oscar Wilde and his œuvre, Radclyffe Hall and The Well of Loneliness have had too much influence on GLBT culture for us simply to dismiss them as relics of the past. Hall’s central character, Stephen Gordon, has moved generations of young readers who have secretly feared (and hoped) that they too were fundamentally different from everyone else they knew and that they were doomed to be rejected and misunderstood by the shallow philistines around them. The judges who feared the influence of this book on the impressionable young were probably onto something, since a reader’s identification with Stephen tends to obscure the textual evidence that her social isolation is not simply a result of human prejudice.

The brief but significant appearance of the “pagan” lesbian character Valerie Seymour serves to show that Stephen is not doomed merely because she loves women but also because her masculine, genetically-determined nature—combined with her traditional Christian value system (which is endorsed by the narrator)—leaves her no room for the ethical fulfillment of her emotional needs. According to God’s laws as Stephen understands them, wholesome joy in the lives of her “people” (“inverts”) can only be an illusion.

Stephen’s life story, like that of a legendary saint or hero, seems to be largely predetermined by forces beyond her control. The story begins, appropriately enough, with the courtship of her Irish mother by her English father, who recognizes his true mate when he meets the fair Anna, who is “all chastity,” on a visit to Ireland. Sir Philip Gordon brings his bride to his ancestral home, which the narrator sees as a structural expression of her personality: “It is indeed like certain lovely women who … belong to a bygone generation—women who in youth were passionate but seemly; difficult to win but when won, all-fulfilling. They are passing away, but their homesteads remain, and such an homestead is Morton.” Sir Philip and Lady Anna seem complementary in every way, and eventually they complete their union by having a child. The unborn baby, whom both parents presume to be a son, is named Stephen. When the baby is born female on Christmas Eve, her father insists on keeping the name he has chosen, that of the first Christian saint.

Stephen’s mother is instinctively repelled by the infant at her breast, who harbors something unrecognizable in a daughter. Lady Anna tries to be a good mother, but she must continually wrestle with her anger at something amiss, especially when she notices the growing child’s resemblance to her father. The “lady of Morton,” who reminds the village peasants of the Virgin Mary, can’t understand her own child, who appears to be both cursed and blessed beyond ordinary parental expectations:

[H]er mother had looked at her curiously, gravely, puzzled by this creature who seemed all contradictions—at one moment so hard, at another so gentle … even Anna had been stirred, as her child had been stirred, by the breath of the meadowsweet under the hedges; for in this they were one, the mother and daughter, having each in her veins the warm Celtic blood that takes note of such things.

Later, Stephen herself can no more ignore the “Celtic blood” that makes her emotionally receptive to the natural world than she could choose to become feminine. An excellent rider, she is given her own horse, and the animal and owner form a kind of feudal bond based on their shared “wildness”: “[H]is eyes were as soft as an Irish morning, and his courage was as bright as an Irish sunrise, and his heart was as young as the wild heart of Ireland, but devoted and loyal and eager for service, and his name was sweet on the tongue as you spoke it—being Raftery, after the poet. Stephen loved Raftery and Raftery loved Stephen.” This identification with Irish youth and poetry suggests both unstoppable creativity and persecution on various levels.

The devotion of Raftery, the good animal servant, is matched by the devotion of the human servants of Morton vis-à-vis their master and mistress. Stephen also shows an instinct for service and self-sacrifice to those she loves, which is presented as both feudal and Christian. As a seven-year-old, Stephen develops a crush on the housemaid, Collins, who complains of pain in the knees. Stephen tells her “gravely”: “I do wish I’d got it—I wish I’d got your housemaid’s knee, Collins, ‘cause that way I could bear it instead of you. I’d like to be awfully hurt for you, Collins, the way that Jesus was hurt for sinners. Suppose I pray hard, don’t you think I might catch it?” The child is bitterly disappointed when God ignores her request for an affliction that would unite her with her beloved.

The God to whom Stephen prays is notably nondenominational, perhaps a response to being raised by an English father and an Irish mother. The “God of creation” that Stephen later seeks in a church in France, land of her exile, seems to transcend specific details of doctrine and ritual. As a Catholic convert, the author tends to place her hero in a universe for which the traditional, hierarchical doctrines of “the Church universal” serve as a reliable guide. Much of the narrative recounts Stephen’s struggles to understand God’s inscrutable will. As a young adult, she is betrayed by each of her earthly parents as she feels she has been betrayed from birth by her heavenly Father. Stephen feels abandoned by the loving father who modeled gentlemanly honor in her life, as well as by the mother who drives her into exile for surrendering to erotic temptation.

Stephen’s father reads and rereads a “slim volume” by a German author, Karl Heinrich Ulrichs, which supposedly “explains Stephen’s nature.” Sir Philip does not want to tell his wife or daughter what he has learned until it’s too late. Sir Philip is killed while pruning a beloved old cedar tree because it is overburdened with snow, as if to punish him for “the sin of his anxious and pitiful heart.” Like Stephen’s friend and spiritual brother Martin (who wants to return to the untamed forest in British Columbia), Sir Philip cares about trees as part of God’s creation.

Deprived of her father’s protection and watched anxiously by her lesbian tutor Puddle, who dares not reveal what she knows, Stephen falls passionately in love with another outsider in the village, Angela Crossby. Like her father before her, Stephen tells her beloved: “all this beauty and peace is for you, because now you’re a part of Morton.” Trapped in a sordid marriage into which she sold herself, Angela encourages Stephen to court her. Like Delilah, however, she is wily and incapable of loyalty. Pressed to make a commitment, Angela taunts her lover: “Could you marry me, Stephen?” Tormented by her inability to offer her own and God’s protection in an honorable marriage to the woman she loves, Stephen buys her an expensive ring set with a “pure” pearl, in a kind of parody of her parents’ engagement.

Angela predictably exposes her lover to the scorn of her enemies after Stephen finds her in flagrante with a bullying male who is Stephen’s oldest rival—an unworthy man who appeals to an unworthy woman. Stephen describes herself as “God’s mistake” in an anguished love letter to Angela, who hands it to her husband to protect herself from the consequences of her infidelity. Angela’s husband completes the betrayal by forwarding the letter to Stephen’s mother, who refuses to continue living under the same roof with her. Stephen chooses to leave Morton, taking the loyal Puddle with her, and enters the purgatory of a world in which she feels homeless.

Although she has inherited wealth, Stephen wants to distinguish herself in a respectable profession to justify her existence to a hostile world. She becomes a novelist with the intention of eventually writing the story of her life: a novel such as The Well of Loneliness.

Stephen is approached by Brockett, a male novelist whom she finds decadent and unmanly (probably based on the playwright Noel Coward), who serves as a Beatrice to her Dante: a guide to the hidden world of fellow “inverts” in Paris. Brockett introduces her to Valerie Seymour, a noted hostess of the Paris demimonde. Stephen initially resents Valerie’s interest in her because she assumes it is as “morbid” as Brockett’s: “she was seeing before her all the outward stigmata of the abnormal—verily the wounds of One nailed to a cross—that was why Valerie sat there approving.” Sensing Stephen’s resentment, Valerie charms her by talking to her “gravely about her work, about books in general; about life in general.”

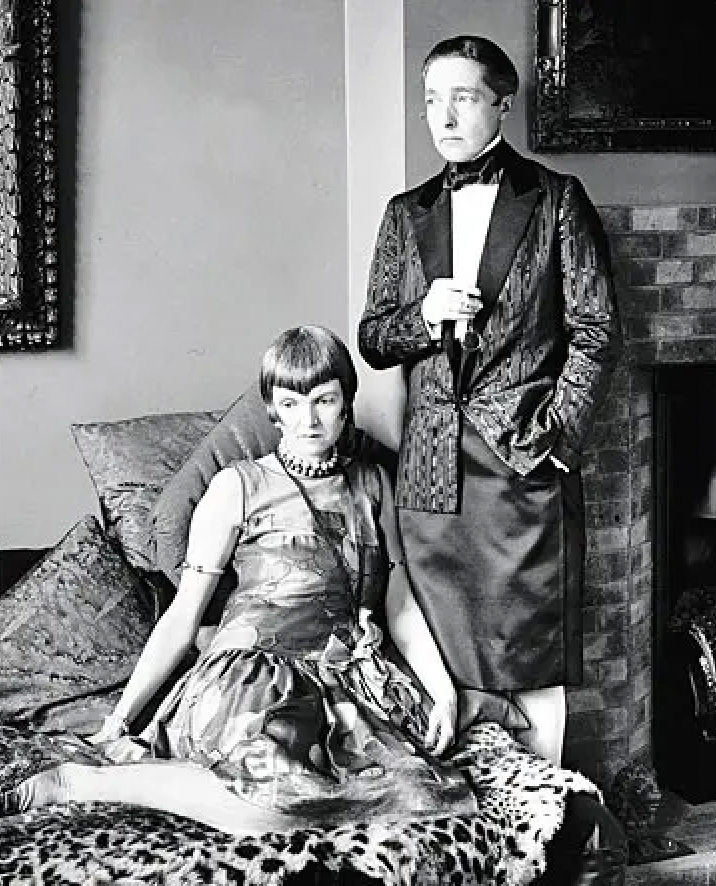

By all accounts, Valerie Seymour is based on an actual person, the bilingual American heiress and writer Natalie Barney, whose Friday salons were legendary in early 20th-century Paris. Partly because the character is drawn from life, she seems out of place among the novel’s otherwise stock characters. Valerie is described from Stephen’s viewpoint as giving an impression of feminine grace, yet she shows a degree of iconoclastic independence that is incompatible with femininity as Stephen understands it.

By Stephen’s conservative standards, Valerie’s home and her life are chaotic: “The first thing that struck Stephen about Valerie’s flat was its large and rather splendid disorder.” Stephen comes to learn that Valerie’s large circle of friends is also “disordered” in the sense of being diverse and not highly respectable; several of her other lesbian friends are dissolute by Stephen’s standards, yet their alcoholism and maudlin despair don’t seem to affect Valerie, who does not indulge in either alcohol or self-pity.

Stephen is at pains to understand Valerie’s apparently effortless success at surviving on her own terms. She attempts to explain this phenomenon to herself:

Stephen began to understand better the charm that many had found in this woman; a charm that lay less in physical attraction than in a great courtesy and understanding, a will to please, a great impulse toward beauty in all its forms. … And as they talked on it dawned upon Stephen that here was no mere libertine in love’s garden, but rather a creature born out of her epoch, a pagan chained to an age that was Christian. … And she thought that she discerned in those luminous eyes, the pale yet ardent light of the fanatic.

Valerie’s “fanaticism” revolves around her determination to create, as far as possible, an alternative culture for herself and her friends. She is pagan in that she resembles a Lesbian in the ancient sense, a follower of the poet Sappho on the island of Lesbos, where Natalie Barney seriously proposed to establish an all-female colony as early as 1901. Valerie appears to be both behind and ahead of her time, a forerunner of the lesbian-separatists of the 1970s and a devotee of the pagan goddesses of old.

On Valerie’s recommendation, Stephen buys an old house with a neglected garden that shows the “disorderly” charm of Valerie herself: “A marble fountain long since choked with weeds, stood in the center of what had been a lawn. In the farthest corner of the garden some hand had erected a semi-circular temple.” This is almost certainly a reference to the actual “Temple of Friendship” that still stands in the garden of the 17th-century house in Paris where Natalie Barney lived for many years.*

Earlier in the novel, the outbreak of war caused Stephen to feel morally compelled to serve her country. Rejected for combat, she’s forced to settle for being an ambulance driver in an all-female unit, where she meets Mary, a young, feminine orphan with whom she falls protectively in love. As her name suggests, Mary is pure-hearted and brave enough to accept a hard fate. Her passionate nature is said to arise from her own “Celtic blood” (which in this case is Welsh). Mary asks Stephen: “Can’t you understand that all that I am belongs to you?” Despite her misgivings, Stephen accepts the gift of Mary’s virginity. Her “bride” has no such reservations: “Mary, because she was perfect woman, would rest without thought, without exultation, without question; finding no need to question since for her there was now only one thing—Stephen.” Although Mary is the mate for whom Stephen has longed, her acceptance of responsibility for Mary’s “unthinking” feminine nature eventually prompts Stephen to make the ultimate sacrifice of driving Mary into the arms of her old friend Martin, an honorable and “natural” man who can be trusted to take care of her.

Stephen, in her role as feudal protector, is devastated when Lady Anna refuses to invite Mary to Morton or to acknowledge her role in Stephen’s life. Stephen is forced to watch helplessly as Mary is ostracized by supposedly “normal” people because of her loyalty to Stephen. Even Mary’s desire to be indispensable to Stephen as a housekeeper and secretary is thwarted by the fact that the household is run by paid staff. Mary languishes in isolation while Stephen is hard at work writing a novel. Recognizing her lover’s need for other human companionship, Stephen descends with her into the night world that Valerie inhabits, where the two women meet other outcasts who resemble damned souls. Stephen unburdens herself to Valerie, whom Mary begins to resent as a rival. Valerie points out the contradictions in Stephen’s personality:

You’re rather a terrible combination: you’ve the nerves of the abnormal … you’re appallingly over-sensitive, Stephen—well, and then … you’ve all the respectable country instincts of the man who cultivates children and acres … one side of your mind is so aggressively tidy … supposing you could bring the two sides of your nature into some sort of friendly amalgamation and compel them to serve you and through you your work—well then I really don’t see what’s to stop you.

To her consternation, Valerie proves most useful to Stephen as a means of driving Mary away. Valerie responds with concern to Stephen’s request: “If you want to pretend that you’re my lover, well, my dear … I wish it were true… All the same… Aren’t you being absurdly self-sacrificing?’” Stephen explains grimly that her strategy is necessary. It succeeds.

Alone in her Calvary, Stephen has a vision of her “children,” the “inverts” of the future who pray for salvation through her, their spokesperson: “They would turn first to God, and then to the world, and then to her. They would cry out accusing: ‘We have asked for bread; will you give us a stone? You, God, in Whom we, the outcast, believe; you, world, into which we are pitilessly born; you, Stephen, who have drained our cup to the dregs—we have asked for bread; will you give us a stone?’”

The novel concludes, in biblical epic style, with Stephen’s anguished prayer: “‘God,’ she gasped, ‘we believe; we have told You we believe… We have not denied You, then rise up and defend us. Acknowledge us, oh God, before the whole world. Give us also the right to our existence!’” But this melodramatic cry is misleading. While claiming to want acceptance, Stephen seems unable to hear Valerie’s admonishment: “even the world’s not as black as it’s painted.” As a woman-loving “pagan,” Valerie would fit in with a modern lesbian-feminist crowd, while Stephen’s martyrdom looks downright medieval.

Author’s Note: A longer version of this article appears in OutSpoken: Perspectives on Queer Identities, co-edited by Dr. Wes Pearce and Jean Hillabold (University of Regina Press, 2013).

Jean Roberta is a widely published writer and scholar based in Regina, Saskatchewan.