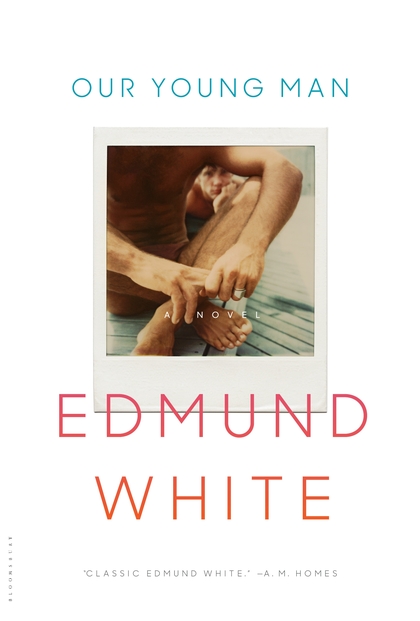

Our Young Man

Our Young Man

by Edmund White

Bloomsbury. 296 pages, $26.

THE IMMENSE APPEAL of Edmund White’s novels, at least for certain readers, is that the fictional world he creates is one in which being gay is the norm. The straight characters are often at sea, not understanding the language and customs surrounding them. The gay characters tend to live in a world of youth, beauty, talent, wit, taste, money—and a lot of sex. White’s second novel, Nocturnes for the King of Naples (1978), evoked gay longing and melancholy through the evocative prose of its youthful narrator. A Boy’s Own Story (1982) bypassed the usual coming-out angst and ended with the young protagonist triumphant in the discovery of his sexuality. Inevitably, AIDS turned this golden world tragic in The Farewell Symphony (1997) and The Married Man (2000), but its inhabitants never entirely lost their gay luster.

White returns to the “palace days” of the 1970s and early 1980s in his latest novel, Our Young Man. Now that the right to marry may have assured the assimilation of gay life into mainstream America, can we view White as more than the chronicler of a disappearing gay milieu? Yes. His often funny and ultimately touching new novel belongs to a classic tradition in American literature, best exemplified by Henry James, in which the sophisticated social structures of Europe encounter the naïve egalitarianism of the U.S., usually with unhappy consequences for the characters involved.

White’s many years of residence in Paris make the international theme in this novel convincing and at times hilarious. “New Yorkers were used to Spanish,” says the narrator, who is not a character but clearly belongs to the world of the novel. “French, however, startled New Yorkers. It was a serious grown-up language, and New Yorkers suspected Parisians considered themselves their equals if not  their superiors.” The novel is the story of Guy, a man of perfect beauty, born in a dreary industrial city in France and discovered on his first trip to Paris by a modeling agent. Guy plays the ingénue, but from the beginning he is knowing and calculating. He’s also charming and, by everyone’s admission, a “nice guy,” unable to deliberately hurt or betray others. With the help of an agent, Pierre-Georges, Guy rises to the top of the Parisian modeling world. By the late ’70s he has landed in New York City, where he’s photographed by Richard Avedon and listed by Forbes as the “world’s fourteenth most successful male model.” And he becomes the darling of the Fire Island Pines. Guy’s earnest efforts to understand his new surroundings are funny and endearing. American slang often baffles him, and he thinks the scents American men wear smell like bubble gum.

their superiors.” The novel is the story of Guy, a man of perfect beauty, born in a dreary industrial city in France and discovered on his first trip to Paris by a modeling agent. Guy plays the ingénue, but from the beginning he is knowing and calculating. He’s also charming and, by everyone’s admission, a “nice guy,” unable to deliberately hurt or betray others. With the help of an agent, Pierre-Georges, Guy rises to the top of the Parisian modeling world. By the late ’70s he has landed in New York City, where he’s photographed by Richard Avedon and listed by Forbes as the “world’s fourteenth most successful male model.” And he becomes the darling of the Fire Island Pines. Guy’s earnest efforts to understand his new surroundings are funny and endearing. American slang often baffles him, and he thinks the scents American men wear smell like bubble gum.

White is a genius at mixing the “show” and “tell” elements of fiction. The narrator moves the story along with brisk paragraphs of exposition. At just the right moment, White interjects a bit of dialogue or a brief scene that makes these extravagant characters real. White’s only equal at this spinning of a magical narrative web may be F. Scott Fitzgerald. At one point, the narrator describes a man in a sauna as having “expensive sapphire eyes and the ruins of good looks,” a line Fitzgerald could have written. Fitzgerald’s novels have a moral center, a voice that records both the brilliant promise and the sad defeat of his characters. In Our Young Man, White’s moral center is presented so subtly that it may escape readers until the final pages. Guy is pursued by many men. He accepts lavish gifts from those who are wealthy and falls in love with those who are beautiful. When fate removes one lover from Guy’s life, he moves on to another, which makes up the plot of the novel.

His beauty undiminished decade after decade, Guy leads a charmed life. But he seems to have no self, to be nothing but a projection of the fantasies he embodies on the runway or in his lovers’ imaginations. As misfortune befalls the people around him, Guy appears selfish when he casually moves on to new experiences. Fred, a wealthy older lover who leaves him a house on Fire Island, dies of AIDS. Andres, a Colombian doctoral student in art history at Rutgers, replaces Fred, but in a misguided attempt to help Guy financially he winds up in prison for forging Salvador Dalí prints. With Andres gone, one day at his gym the lonely Guy notices identical twin brothers from Minnesota, young, blond, and beautiful. One of them, Kevin, is gay and soon moves in with Guy. Kevin, almost half Guy’s age, has no idea how old this famous model really is. Their relationship sets the stage for Guy’s transformation from puer aeternus to a man who recognizes the inevitability of aging and the responsibilities of love.

Most of the characters in the novel are presented as fully formed: they do not change and they do not surprise. Soon after they meet, Pierre-Georges, who becomes Guy’s delightfully bitchy confidant, calls the young man a “black hole in space.” “You’re beautiful and everybody projects onto you what they’re looking for, which is easy to do since you don’t stand for anything definite.” Minus a measure of hard-earned self-knowledge, this describes Guy as he appears at the end of the novel. Kevin is the one character who does develop, changing from a naïve, seemingly shallow Midwestern boy to a young man who knows what he wants to do with his life, which is to become a career diplomat in South America. Like all Americans, Kevin believes he can achieve any goal through hard work. Under Guy’s expert tutelage, Kevin also becomes a sexually confident gay man.

As Kevin’s fortunes rise, Guy’s decline. Guy is defined—and limited—by his beauty, which inevitably begins to fade. When Andres returns from prison, Guy knows what he must do. As Henry James’ novel The Ambassadors draws to a close, Madame de Vionnet, a beautiful, worldly Parisian woman, accepts the loss of her lover Chad Newsome, the young American she has introduced to the ways of the world. He leaves her to return to his predestined place, his family business in Massachusetts. The New World and the Old are ultimately irreconcilable, even if their inhabitants have a lot to learn from each other. Edmund White switches up the characters, but his enterprise in this novel is similar to that of James. Like his 19th-century countrywoman, Guy is a realist. He frees Kevin to live, at least for a time, in his world of unlimited possibilities. His American prospects diminished, Guy returns to Europe with a family of sorts, the disgraced Andres and a straight stoner nephew who’s left in his care. The surprisingly satisfying resolution of Our Young Man is White’s way of showing readers, especially those for whom being gay is the norm, how to accept who they are, and where they belong, with grace.

Daniel Burr is a frequent contributor to this magazine.