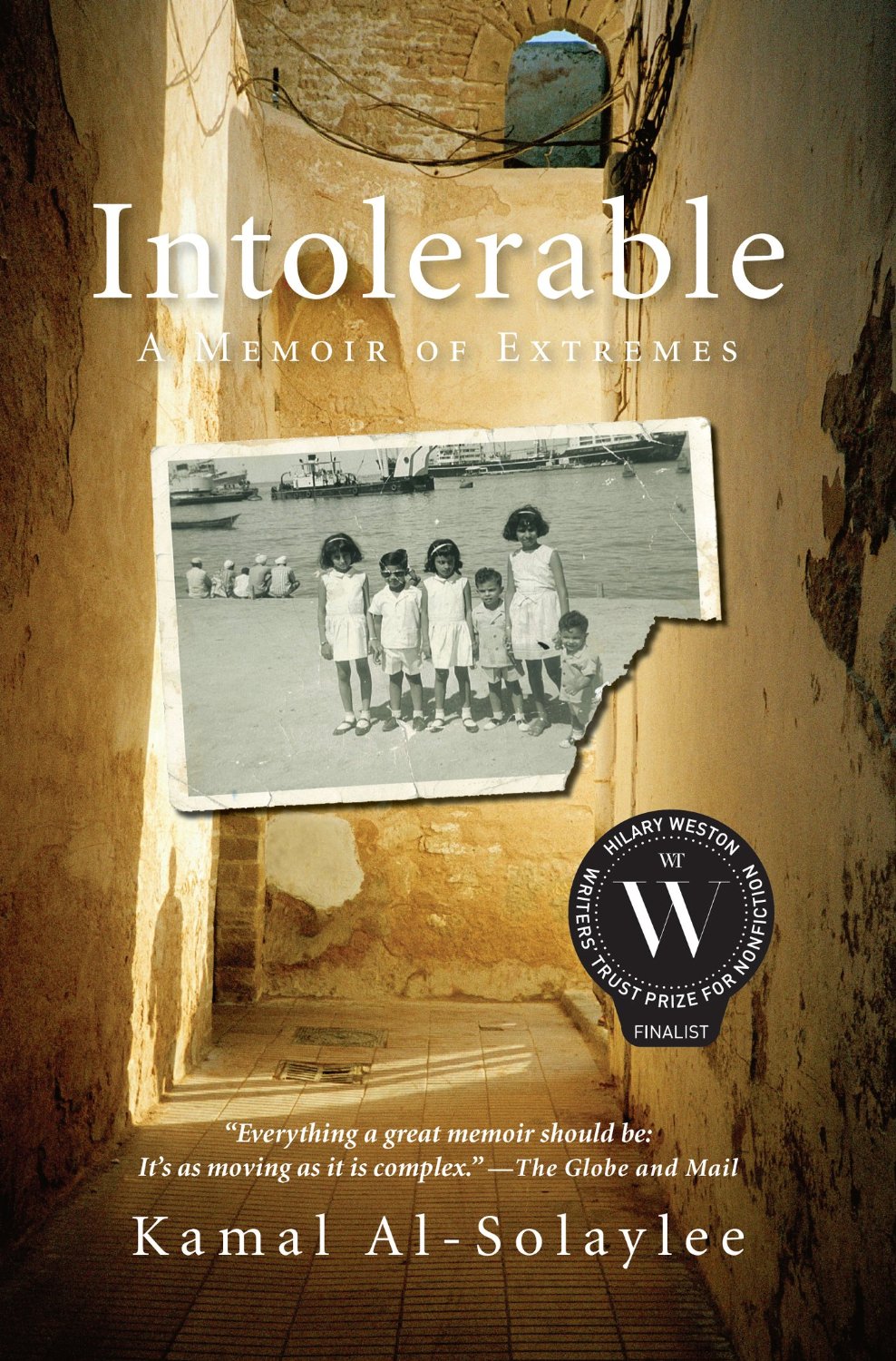

Intolerable: A Memoir of Extremes

Intolerable: A Memoir of Extremes

by Kamal Al-Solaylee

Harper Perennial. 204 pages, $15.99

WHILE family memoirs are often drenched in anguish, Kamal Al-Solaylee’s Intolerable takes the genre to a new level. The Toronto-based journalist and university professor reaches back to his parents’ history, from Yemen in the ’60s through Beirut, Cairo, and back to Yemen up to the Arab Spring, in agonizing, heart-wrenching detail. Along the way, he illuminates the complex struggles and historical moments that have shaped the region, all through his own very personal vantage point.

Al-Solaylee begins with loving portraits of his Yemeni parents. His mother was a poor, illiterate woman, and his father a proud Yemeni who was also an avid Anglophile with a UK passport. His father managed to make a reasonable living flipping real estate until the colonial powers were overthrown and nationalist socialism moved in. With his properties seized by the state, the senior Al-Solaylee had little choice but to move to greener pastures. And so began the journey of the family with eleven children: first moving to Beirut but fleeing the war in Lebanon to go to Cairo (where they couldn’t quite fit in), only to return to Yemen as a last resort at a time when ethnic, religious, and economic friction became too much to bear.

Al-Solaylee tells his family’s story in a no-nonsense writing style, a perfect counterpoint to the intricate twists and turns in each chapter. He lucidly illustrates the evolution of the region—or devolution, as he sees it—through the eyes of someone who felt forced to remove himself from it entirely. There are touching memories, in particular, of times with his sisters in Cairo, when they would go shopping and splurge on colorful clothing and records by Western pop artists. At this time, when Al-Solaylee was in his early teens, his sisters had actual choices in their lives: they were outspoken and enjoyed dressing well and wearing a bit of make-up.

But any independence by the female members of the family was short-lived. He recalls Egyptian President Anwar Sadat’s historic 1977 visit to Israel, as the family huddled around the television to watch it live, suggesting “the only comparable history-making event in North America would be the moon landing in 1969.” But while some in the West saw the Egypt-Israel peace accord as hopeful, many Egyptians viewed Sadat as a sellout who strengthened the Muslim Brotherhood, the group that would ultimately assassinate him.

As the entire Egyptian middle class began to get squeezed, the Al-Solaylee patriarch made the painful decision to return to Yemen. His eldest brother had become increasingly swept up in Muslim extremism, often berating his sisters for wearing make-up and refusing to wear veils, telling them they looked like whores. Things would only get worse in Yemen.

If all of these conflicting questions of identity weren’t enough, Kamal Al-Solaylee also had to contend with the fact that he’s gay. In one scene, his father looks at his son anxiously as they watch a Barbra Streisand movie together, with the young Kamal looking at the American Jewish singer in complete adoration. The gay thing, on top of everything else, meant that Kamal understandably felt that he had no other option for survival but to flee to Britain to pursue a university education. Expecting histrionics from his mother upon telling her his plan, this self-described mama’s boy recalls her saying one word to him: “ihrab,” which means escape.

Al-Solaylee ultimately manages to make a good life for himself in Toronto—a city he loves so much that he dedicates the entire book to it—but he is bogged down by staggering guilt and depression about the family he left behind, in particular his sisters. They bluntly describe their existence in Yemen as hell, stuck in a civil war and encumbered by religious repression that results in what Al-Solaylee refers to as “gender apartheid.”

Intolerable features a number of family photos throughout, as his father insisted on documenting as much of their childhood as possible. In his last visit to Yemen, Al-Solaylee describes his horrifying realization that his siblings no longer took photos, as it became clear there was nothing about their lives they wanted to record. Worse, they never looked at old photos, as remembering a happier past was too painful.

Intolerable crosses so many lines of identity as to make a reader’s head spin: class, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, nationality, religion, and degrees of religious observance. This beautiful book about a family’s tortured relationship to history—and a region’s fraught relationship to modernity—is everything a great memoir should be: poignant, complex and haunting. It resonates all the more powerfully right now, given that the entire region is in such a dire state of turmoil. But beyond the current events, this is a timeless book, one of the best I’ve read in the past decade.

________________________________________________________

Matthew Hays is the author of The View from Here: Conversations with Gay and Lesbian Filmmakers.