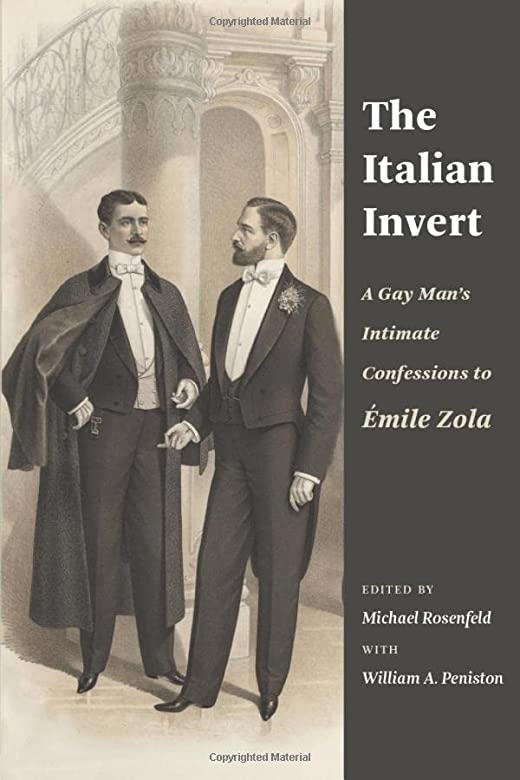

THE ITALIAN INVERT

THE ITALIAN INVERT

A Gay Man’s Intimate Confessions to Émile Zola

Edited by Michael Rosenfeld with William A. Peniston

Columbia U. Press. 272 pages, $30.

SOME TIME around 1888, a 23-year-old Italian aristocrat wrote an anonymous, undated letter to the French writer Émile Zola, in which he confessed to “the plight of a soul who seems to be pursued by a horrible fatality.” The Italian—who described himself as “a pretty, cute, perfumed, irreproachably elegant, frivolous, and secretly debauched being”—was a homosexual, and he wanted to give Zola, an author he greatly admired, material the French master might use in one of his novels.

To that end, the Italian recounted his experiences as an adolescent, when he first realized that he felt an irresistible attraction to men. He told Zola about his early passions: a love of literature, the pomp of Catholicism, and “dresses with trains.” He was particularly keen on the heroes of the Trojan War, especially Paris, “imagining myself as Andromache in order to be able to hold him in my arms.” As for his sexual awakening, by thirteen he had learned about masturbation from the family’s groom; another servant let him stroke his “virile member.”

During the Italian’s military service, when the contrast between his pretty face and his hussar’s uniform lent him the “charms of a transvestite,” he enjoyed his first consummated homosexual experience with a barracks mate. When the friend was killed in a drunken quarrel, the Italian vowed “not to revert to the horrible error of my senses.”

The next morning, the Italian wrote a second letter to Zola, giving him even more details of his “filthy tale.” He told Zola of an affair with a 53-year-old friend of his family, who tried to fuck him, though the physical pain “made me withdraw from the violent act.” Other adventures followed, all of which left the Italian with the “ardent desire to die in the flower of my youth and beauty.” A third letter soon followed in which the Italian provided Zola with still more details of his personality and passions.

The next morning, the Italian wrote a second letter to Zola, giving him even more details of his “filthy tale.” He told Zola of an affair with a 53-year-old friend of his family, who tried to fuck him, though the physical pain “made me withdraw from the violent act.” Other adventures followed, all of which left the Italian with the “ardent desire to die in the flower of my youth and beauty.” A third letter soon followed in which the Italian provided Zola with still more details of his personality and passions.

It’s fascinating to follow the Italian man’s struggles to come up with language with which to describe himself and his homosexual experiences. Words like debauchery, moral ugliness, perverse, corrupt, sick, and monstrous pepper these three letters. At the same time, he could not deny the beauty that he sometimes felt in his homosexual love affairs, a beauty which, he declared, surpassed everything else. “For me all vices, all crimes are excused by it.” He came to realize that “as long as you are alive, you can have pleasure.”

Initially, Zola didn’t know what to do with this confession, but the letters touched him with their sincerity and “eloquence of truth.” And while he felt that “public order” must be upheld by morality and justice, nevertheless he saw no reason to condemn this unfortunate man. Eventually, he handed over the Italian’s letters to a young medical doctor in his acquaintance, Georges Saint-Paul. The doctor, eager to challenge himself with a new research project, turned his attention to the study of “sexual perversion.” By 1895, he had written a book, Defects and Poisons: Sexual Perversion and Perversity, published under the pseudonym Dr. Laupts, to which Zola courageously supplied a preface. The book included the Italian’s letters, censored in part, and Saint-Paul’s analysis of this person with “tainted instincts.”

As heroic and forward-looking as Saint-Paul was in publishing the Italian’s confession, his opinions were still mired in the prejudices and ignorance of the day. He thought the Italian a “strange, revolting, and truly pitiful person,” and interpreted his behavior as a clear indication that he desired to be a woman. He counseled the French educational establishment to create a system of diversions—physical and intellectual—so that the “secret vices” of many young men would not be given a chance to blossom.

The appearance of Defects and Poisons prompted gay men in France and elsewhere to write to “Dr. Laupts.” Many told him that they were not ashamed of themselves and in fact advocated for changes in society, not personal “cures.” Meanwhile, the Italian kept hoping to find a character in one of Zola’s subsequent novels based on himself. As the years went on, he resigned himself to the fact that he should not expect Zola to do “what Balzac himself didn’t dare do.”

The story might have ended there but for the Italian’s stupendous chance discovery of Saint-Paul’s book in a shop window one day in 1896. He wrote to “Dr. Laupts,” thanking him for the discretion the doctor had shown in his use of the letters and offering more stories about the “treacherous affliction that torments me.” He provided detailed accounts of his sex life since those original letters, and speculated on the causes of his sexual orientation. By the end of this long “sequel”—it runs to 38 printed pages—the Italian came to accept who he was: “a strange being, neither man nor woman, or, rather, both man and woman at the same time.”

Fourteen years later, when Saint-Paul brought out a second edition of the book, his thinking about homosexuality had changed to the extent that he now accepted that there were “born homosexuals,” though he was quick to say that homosexuality was “a rarity” in France. A third edition was published in 1930. In it, Saint-Paul acknowledged that the thinking on same-sex love had changed a lot since the 1910 edition, and he was now more cautious about unequivocal statements and interpretations regarding the still new field of homosexual studies.

Might the Italian’s tale, only now fully revealed after its earlier expurgated versions, be considered “the foundational autobiography of gender fluidity”? Psychiatrist Vernon Rosario poses this question in his excellent foreword to The Italian Invert. Whatever the case, Rosario says we can still “unequivocally admire” the Italian for coping with the hostility he encountered and, in the end, for enthusiastically embracing his sexual uniqueness.

The Italian Invert is an important addition to the field of queer studies. The Italian’s story—full of despair, confusion, narcissism, sexual yearning, snobbery, and ultimate self-acceptance—is as compelling as it is candid. Moreover, as editor Michael Rosenfeld points out, Zola’s collaboration with Saint-Paul was an extraordinary example of “goodwill and courage,” even though both men struggled to understand the complete reality of homosexuality. The ménage à trois of Zola, Saint-Paul, and the Italian, as strange as it was, has left us with a document that provides both the casual reader and the scholar with fascinating material.

Philip Gambone, a regular contributor to these pages, is the author of As Far As I Can Tell: Finding My Father in World War II (2020).