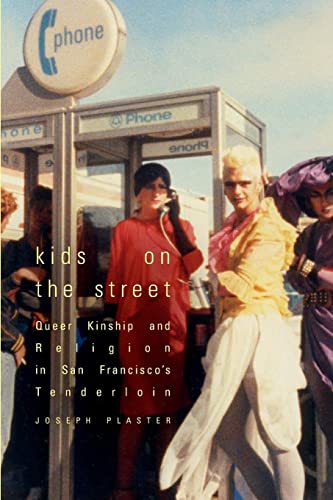

KIDS ON THE STREET

KIDS ON THE STREET

Queer Kinship and Religion in San Francisco’s Tenderloin

by Joseph Plaster

Duke Univ. Press. 368 pages, $28.95

JOSEPH PLASTER’S Kids on the Street is an in-depth sociological study of “throwaway kids”: abandoned and runaway queer youths marginalized by their sexuality and/or gender identity, who forged informal networks of mutual support to navigate and survive on the streets and alleys and in flophouses in the vice-ridden districts of America’s major cities. Although the book focuses primarily on San Francisco’s Tenderloin district and the adjacent Polk Street area from the 1950s to the present, Plaster also discusses the history of other cities’ Tenderloin counterparts. Combining secondary research in various archives with his own participation in on-the-street support efforts and his tape-recorded interviews with dozens of street kids and others, Plaster presents an alternative queer history that’s largely disregarded in the prevailing account of LGBT history as a long but steady march from subjection to equality.

“Tenderloin districts” can be thought of as “red-light districts,” sharply delineated and easily recognized “zones of abandonment where the degradation and immorality associated with the poor, sexual and gender deviants, and racialized populations could be contained and cordoned off from respectable white families and homes.” Marked by dilapidated SROs (single-resident-only rooms in hotels), peepshows, porn theaters, dive bars, seedy pool halls, cheap diners, all-night coffee shops, and other “dirty, dangerous, and duplicitous” enterprises, Tenderloin districts are “the dumping ground … [for]the people and problems [that]our society … decided to ignore: the older person, the homosexual [and transgender], the alcoholic, the dope user, the Black, the immigrant, the uneducated, the dislocated alienated youth … [and other]dangerous blights on downtowns, in need of arrest, punishment, or reform.” The street kids are generally unhoused, alcohol- and/or drug-addicted, and either the perpetrators or the victims (or both) of the district’s violence and criminality. Think of the Times Square area of New York City before Mayor Giuliani’s crackdown and the “Disneyfication” of the area.

Historically, these cities’ laws against homosexuality, cross-dressing, and vagrancy presented the opportunity for unscrupulous crooked cops to extort the owners of gay bars and “shak[e]down the homos, hustlers, hookers, and dealers.” The queer street kids who live and operate in these districts have mostly fled unbearable home environments. They are often teenagers (or even younger) who rebelled against physical violence and sexual abuse at the hands of fathers or uncles. (Plaster interviewed one young man who recounted the horrifying experience of being sexualized by his father and then passed around among his uncles from the time that he was only three years old until he escaped to San Francisco.) Generally uneducated and unemployable, they have exchanged one hellish environment for another, where day-to-day survival is their primary concern.

In San Francisco in the late 1950s and ‘60s, as white flight to the suburbs depleted the city’s population of white blue-collar workers and gentrification efforts to “clean up” and “beautify” the Tenderloin closed the once flourishing bars, pool halls, and theaters, the queer street kids and other Tenderloin denizens moved to the nearby Polk Street area. There they found low-income housing options, cheap diners, and coffee shops. As many straight bars welcomed the change and became gay bars, Polk Street became the center of LGBT life before the Castro Street area developed in the 1970s. The first Gay Pride march traversed Polk Street in 1970, as did the first Gay Shame march years later.

The thriving gay scene lured the hustlers who had operated almost exclusively in the Tenderloin. Nearly all of the men and transgender women that Plaster interviewed had hustled on the “Polkstrasse,” the ten-block area from Sacramento Street at the northern end to Civic Center at the southern. Indeed, the gay businesses along Polk Street (at one point some twenty-plus bars, porn theaters, and SROs) thrived because of the street hustling. Several bars (such as the Q.T. and the Rendezvous) operated as places where hustlers hung out searching for customers. The Motherlode and Divas were known for their transgender clientele and johns who sought them out. Often, the bartenders and bouncers of these places served as procurers for the hustlers or as unofficial employment agents, finding work for them in the bars and diners along the streets. This reciprocal arrangement benefitted both the hustlers and the bars. The johns seeking companionship for the night spent a lot of money buying drinks in the bars and in the street’s cheap hotels, and the hustlers made more money in the bars than cruising the streets.

Life for these young people was extremely difficult, full of violence at the hands of johns, thievery by other hustlers, and the deterioration of their health and looks from living on the streets. However, many of them found or formed “street families,” fellow streetworkers who hung out together, pooling their money to secure housing for a night or a meal at the diners, warning each other away from johns who got violent or didn’t pay, taking sick friends to the free clinics, and otherwise caring for one another in ways their families had never done. Plaster refers to this as the “moral economy,” based upon reciprocity and fairness—the street kids all “had each other’s backs.” Many individuals and groups offered services such as free needle exchange and communal dinners provided by religious groups. Clergymen such as River Sims and Raymond Broshears organized “street churches” complete with Catholic-inspired rituals; they “ordained” some of the street kids to offer aid to other street kids. Other reformers, social workers, sociologists, LGBT organizers, and Protestant ministers also intervened in the lives of the street kids. Organizations such as Glide Methodist Church and Vanguard (a mutual aid group founded in 1966) provided resources to street kids as well.

The AIDS epidemic of the 1980s and ’90s decimated Polk Street denizens. Queer businesses suffered a decline in patronage. The market for hustlers also diminished as many succumbed to AIDS and johns grew wary of contracting HIV. Many hustlers who once prowled Polk Street turned to the burgeoning internet as a means of advertising their wares. In the early 2000s, as the tech boom drew more affluent people to San Francisco, rents and the price of everything else skyrocketed. Gentrification of the Polk Street area forced many businesses to close and displaced the hustlers, transgender women, and other queer folks.

These days, Polk Street is nearly devoid of queer culture. There remains only one gay bar, The Cinch, at the northern end of the district. The once-queer spaces have been replaced by straight bars, nightclubs, high-ticket restaurants, upscale condominiums, and expensive boutiques. Only fading memories remain of Polk Street in its heyday. The ghosts of my friends at the long-gone Polk Gulch Saloon still haunt me whenever I walk by.

Kids on the Street is an admirable, thoroughly researched, and carefully documented history of the once vibrant queer culture of the Tenderloin and Polk Street. Featuring scores of interviews with one-time Polk Street denizens, it is also a lament for the displacement of the multiracial, multigender culture of San Francisco’s first post-Stonewall queer district. Drawing attention to that once-thriving, often overlooked culture, the book is a valuable contribution to queer history.

Hank Trout has served as editor at a number of publications, most recently as senior editor for A&U: America’s AIDS Magazine.