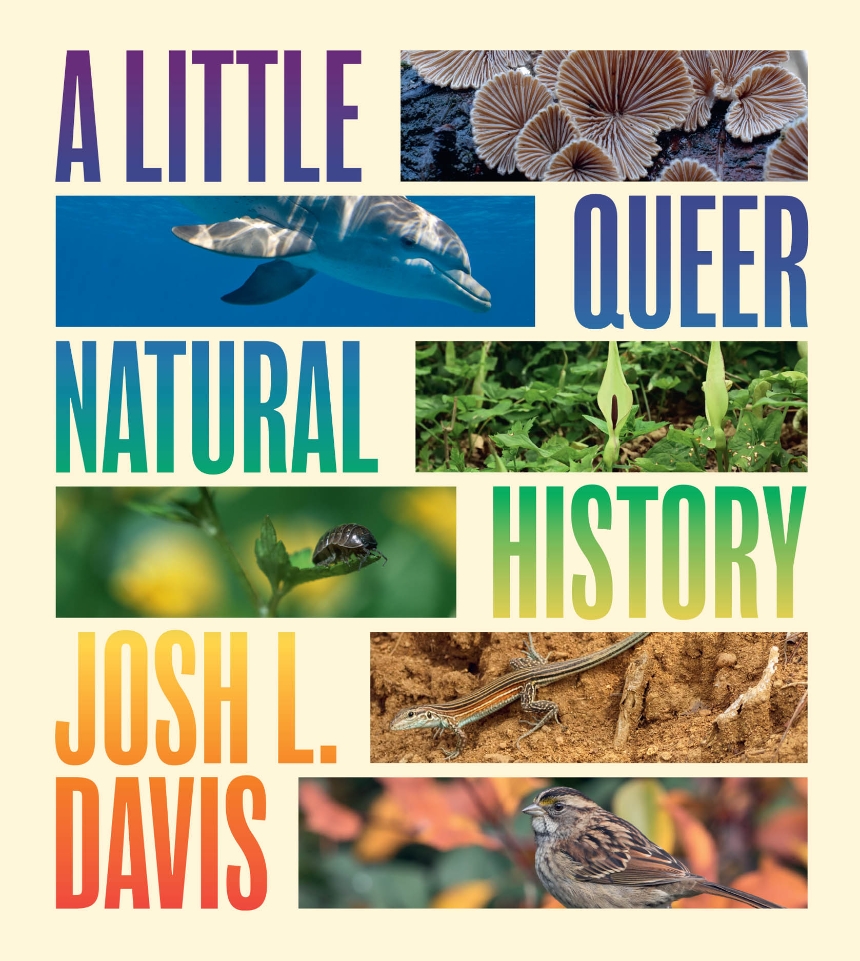

A LITTLE QUEER NATURAL HISTORY

A LITTLE QUEER NATURAL HISTORY

by Josh L. Davis

University of Chicago Press

128 pages, $16.

IT HAS ALWAYS ASTONISHED ME, given the number of people attracted to their own sex in this world and the pain that being homosexual has caused a significant number of them, that so little has been done to find the “cause” of their divergence from the norm. Why, I used to wonder, did the parents of a friend of mine from Worcester, Massachusetts, produce four homosexuals out of five children—one of them the first openly gay judge in that state? Was it something about the mother, whether she drank alcohol during pregnancy, or the level of the father’s testosterone during conception, or the legendary “gay gene”? What determined the outcome of this exchange of DNA? It was ordinary curiosity, I suppose, to wonder about such things, except that I had a personal stake in finding out. It rankled me when homophobes claimed that I had simply “chosen” to be gay—presumably because homosexuals were sybarites who just wanted to have fun, to be free of the burdens of parenthood, to live for pleasure.

Homosexuals replied with a question of their own: Do you really think anyone would choose a life as difficult as this? If only we could find the “cause” of homosexuality, I thought, we could prove that it wasn’t a choice. That’s why I perked up in 1991 when a British scientist named Simon LeVay noticed that the hypothalamus glands of a group of male homosexuals he’d studied were smaller than those of women and heterosexual men. But this excitement did not last. The problem was that there was no way to know if the smaller glands were a result or a cause of same-sex attraction. The findings were attacked on all sides, and the attempt to explain why some of us are drawn to our own sex was replaced by the El Dorado of the “gay gene,” which inspired Jonathan Tolins to write a play called The Twilight of the Golds, in which a couple is informed by doctors that the child they’re about to have will be homosexual. So do they want to abort? In other words, homosexuality as a birth defect.

Enter the lesbian seagulls.

The lesbian seagulls were discovered in 1972 nesting off the coast of California on one of the Channel Islands. They were not the first instance of homosexuality in birds to be noticed, but they created a sensation, as Joshua Davis explains in his fascinating new book, A Little Queer Natural History. This happened because they were noticed just when the Gay Liberation movement was on the rise. In fact, same-sex relations in the animal kingdom had been noticed early in the 19th century, when a German schoolteacher named August Kelch came upon two male common cockchafers (aka doodlebugs) copulating in the woods; though that was explained, as so much same-sex copulation would be by heterosexual scientists, as simply an exercise in dominance. But in 1864, a Russian diplomat and entomologist named Carl Osten-Sacken observed two more doodlebugs having sex and noted that the larger one was the passive partner, not the smaller, so it wasn’t about power. Then what was it? In 1896, the French entomologist Henri Gadeau de Kerville argued that male-to-male copulation in beetles came in two forms: one based on necessity, the other on preference.

Then, in 1923, ornithologist John Peacock Ritchie was rambling around a loch west of Glasgow when he came upon two black swans nesting. After stopping to take a photograph, he chased the birds off to see what was in the nest. The nest was empty. A week later he checked again and there were still no eggs. “At first, he suspected that railway workers nearby had stolen the swans’ eggs,” Davis writes, “but on a third visit to the pair the nest remained bare. After several more visits in the following weeks, and a re-examination of the photograph he had taken, he noticed two large black knobs at the base of the swans’ bills, which revealed that the two birds were both male. The picture that Ritchie took is now thought to be the first confirmed photograph of queer animals.”

Finally, in 1956, a Canadian zoologist named Anne Innis Dagg “made history. At the age of 23, she became the first person we know of to study wild animals in Africa scientifically.” After studying 125 mammalian species, she concluded that “adult homosexual behavior is widespread among male and female mammals.” In some populations of giraffes, over 94 percent of observed behavior was homosexual. Not only did male giraffes literally neck, but they licked the genitals of their partners, mounted them and ejaculated. Skeptical scientists argued that the giraffes’ dalliance was about dominance, not sex (though surely sex is often about dominance, at least among humans).

A Little Queer Natural History is made up of short chapters laced with tales of scientific discovery like these; but, along with some spectacular photographs, it mostly consists of descriptions of the reproductive strategies of various living species, from the European eel to the African yew tree to penguins, apes, sheep, mushrooms, barklice, and flowering plants like the Chinese shell ginger. By the time we reach the latter, we are so far from human reproduction that one finds oneself wondering: “Just what is sex, anyway?” That’s because the creatures discussed—moss mites and cane toads, lizards and killifish, ash trees and fungi—are as foreign to us as creatures from another planet. While the book begins by drawing parallels between human and animal homosexuality, it ends with forms of reproduction that cannot be compared to anything we do. That homosexuality occurs in other mammals is the least of it; we are living in a universe of insane complexity. The organisms chosen illustrate, among other things, parthenogenesis (virgin birth), androgenesis (male chromosomes only), environment-dependent sex determination, temporal sex, intersex, changeable sex, asexuality, bisexuality, bacteria-dependent and temperature-dependent sex determination—which puts us a long way from the view dating back to St. Thomas Aquinas (the source of so many teachings of the Catholic Church) that homosexuality is neither reasonable nor natural.

A Little Queer Natural History is made up of short chapters laced with tales of scientific discovery like these; but, along with some spectacular photographs, it mostly consists of descriptions of the reproductive strategies of various living species, from the European eel to the African yew tree to penguins, apes, sheep, mushrooms, barklice, and flowering plants like the Chinese shell ginger. By the time we reach the latter, we are so far from human reproduction that one finds oneself wondering: “Just what is sex, anyway?” That’s because the creatures discussed—moss mites and cane toads, lizards and killifish, ash trees and fungi—are as foreign to us as creatures from another planet. While the book begins by drawing parallels between human and animal homosexuality, it ends with forms of reproduction that cannot be compared to anything we do. That homosexuality occurs in other mammals is the least of it; we are living in a universe of insane complexity. The organisms chosen illustrate, among other things, parthenogenesis (virgin birth), androgenesis (male chromosomes only), environment-dependent sex determination, temporal sex, intersex, changeable sex, asexuality, bisexuality, bacteria-dependent and temperature-dependent sex determination—which puts us a long way from the view dating back to St. Thomas Aquinas (the source of so many teachings of the Catholic Church) that homosexuality is neither reasonable nor natural.

What is natural is astounding. Consider, for instance, the spotted hyena, a species that would seem to be a poster child for how not to procreate: the female has a clitoris so long and thick it resembles an erect penis, but being able to penetrate the male with it surely cannot make up for the painful fact that she gives birth through the same appendage. Consider the common pill woodlouse, which hosts a bacterium that insists for some reason on eliminating all male chromosomes, so that only females survive to mate with one another. Or the mangrove killfish, self-fertilizing hermaphrodites that reproduce by themselves, or the Chinese shell ginger, which changes sex according to the time of day, or the common cockchafer, which looks like a cockroach with white fuzzy hair on its back and shoulders—a not inaccurate description, no doubt, of what older gay men look like to younger ones. The latter forced l9th-century European entomologists to admit that two males were indeed having sex with one another. Or consider the male giraffes that live in same-sex colonies, or the forty percent of male Guianan cock-of-the-rocks (a bird so spectacular it must be gay), who engage in homosexual behavior. Then there are the apes (the chimpanzees and bonobos), the domestic sheep, or the Western gulls, the European eels, the Green sea turtles (whose sex is determined by the temperature of the sea), the microscopic moss mites, which reproduce asexually, or the most abundant of all organisms on earth, the fungi.

By the time we have met all the many species that Davis introduces, we understand that nature includes numerous methods of reproduction that are, to put it mildly, impossible to anthropomorphize. Indeed, somewhere between the Chinese shell ginger and the last chapter‘s barklice, the mind has so glazed over that one finds oneself reading sentences three or four times to understand what they’re saying. This book, while entertaining and brief, is not quite written for the lay reader. Although the entries are brief and the English clear—and the photographs are a joy—one feels a bit thick when reading passages like the following.

By the time we have met all the many species that Davis introduces, we understand that nature includes numerous methods of reproduction that are, to put it mildly, impossible to anthropomorphize. Indeed, somewhere between the Chinese shell ginger and the last chapter‘s barklice, the mind has so glazed over that one finds oneself reading sentences three or four times to understand what they’re saying. This book, while entertaining and brief, is not quite written for the lay reader. Although the entries are brief and the English clear—and the photographs are a joy—one feels a bit thick when reading passages like the following.

Sexual reproduction and mating comparability in fungi is largely controlled by the genes found at a point (known as a locus) on the genome known as the “mating type,” abbreviated to “MT.” These genes can produce different variations of a protein, meaning individual mating types are needed for successful sexual reproduction. Roughly speaking, this can be thought of in similar terms to the genes on the X and Y chromosomes in mammals, and so mating types are, to a certain extent, analogous to sex.

One feels like Katharine Hepburn listening to Cary Grant in Bringing Up Baby. The general reader may even come to the conclusion that what he or she really needs to do is read Darwin, for it is evolution itself that one may not understand—a concept most of us think we get the gist of but whose details remain sketchy. Then, too, there is simply the drama of the scientific method. How did biologists determine, in the case of barklice, that it’s the female that penetrates the male by inserting a tube into the male’s little package of sperm and nutrients, which the male allows the female to suck out after he ejaculates?

I STARTED reading Davis’ book thinking it might bring a sort of comfort or reassurance that we’re not alone in the universe, or even shed light on the reason some of us are homosexual. However, as Davis writes: “This book is not a justification for queer behaviors—animal or otherwise—because these behaviors require no justification.” It’s more a cabinet of curiosities, or a l9th-century-style traveling fair in which the bearded lady is used to entice the yokels into the tent. It shows us some of the incredible, mind-boggling sexual strategies in the known universe—queer in the original sense of the word—a long way from skirts and jockstraps. The moss mite, which reproduces asexually (which seems to the lay person a lot like cloning), has been doing so for 400 million years. But it sheds no light on the cause of homosexuality. It doesn’t explain why the parents of my friend from Worcester produced four homosexual children, or why I think my favorite aunt (on my father’s side) and my favorite uncle (on my mother’s side) were gay. Having perused this extraordinary collection of creatures that do not reproduce along the lines that humans do, I know no more about why I instinctively bonded with my aunt and uncle growing up.

In the final scene of Fellini’s La Dolce Vita, everyone leaves the house party and walks out onto the beach, and the young queen, dressed as an angel, informs Marcello Mastroianni that by the year 2000 everyone will be gay. That, obviously, has not happened—so why is homosexuality still seen by some as a threat to humanity? Two things, I suspect: people still think, like St. Thomas Aquinas, that homosexuality is neither natural nor reasonable, and, on a more visceral level, most people are repelled by sex that they themselves do not engage in or desire. A Little Queer Natural History shows two things: a) that we are not the only animals to have homosexual sex; and b) that our version of sex is hardly the only one in nature. The book begins with creatures that probably will encourage an anthropomorphic fondness in the reader and ends with organisms with which we cannot possibly identify. We’re like giraffes, gulls, bonobos, penguins, swans, other large apes, and sheep, but we do not resemble the Chinese shell ginger or the bluegill surf fish, the splitgill mushroom or, heaven help us, the Dungowan bush tomato.

Sociobiologists have explained us as uncles and aunts who can help the younger generation, and thus further the interests of the heterosexual pair that founded the family, or even theorized that homosexual behavior among the larger apes reduces their tendency to fight and kill each other, but we still don’t know why three or more percent of homo sapiens, or eight percent of rams, or most giraffes and domestic sheep exhibit same-sex desire. It may comfort us to know that male bonobos and giraffes have lots of sex—a certain mammalian loneliness was surely one reason for my desire to know about these matters—but there is a limitation to all this research. As Davis points out, we cannot ask the Bluebill sunfish or the common pill woodlouse how they feel about the sex they have, or whether domestic sheep consider themselves gay, or if there is pleasure or comfort in their orgasm.

All of these questions are made more fraught by the current culture wars over trans rights, public bathrooms, and puberty blockers. Is the trans movement a harbinger of some sexual evolution that we cannot foresee? A thousand years from now, will we have sex like Jane Fonda and John Phillip Law in the movie Barbarella, by simply touching fingertips? Are we still evolving in the matter of sex? Why does a man in 2025 have sex in essentially the same way as did a man 2,000 or more years ago? To religious conservatives, homosexuality is a dead end, a sign of decadence. Might it, and might the trans phenomenon, be something else? Sex research always seems to be finding new things, and, as Davis points out, scientific findings often have a political dimension.

One finishes this book no nearer to an “explanation” for homosexuality, but one feels comforted and somewhat awestruck to know that we are not alone. As Cole Porter so wisely pointed out: “Electric eels, I might add, do it,/ Though it shocks them, I know./ Why ask if shad do it?/ Waiter, bring me shad roe!”

Andrew Holleran’s latest novel is The Kingdom of Sand. His other novels include Grief and The Beauty of Men.