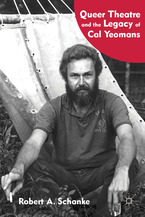

Queer Theatre and the Legacy of Cal Yeomans

Queer Theatre and the Legacy of Cal Yeomans

by Robert Schanke

Palgrave/MacMillan

239 pages, $85.

NOT MANY PEOPLE, I suspect, have heard of the playwright Cal Yeomans, but then not many had heard of Samuel Steward before last year, when Secret Historian, Justin Spring’s biography, was published and nominated for the National Book Award. The similarities between the two are striking. Both Yeomans and Steward were writers whose lives were full of the difficulties of homosexuals of their generation; both lived on the margins of artistic success; both were obsessed with sex; and both left behind a treasure trove of papers.

Both men, to continue, grew up in a small town and moved to a big city—Chicago in Steward’s case, New York in Yeomans’s—and both failed to achieve their dreams. Steward ended up writing porn and Yeomans wrote mostly unproduced gay plays. They did belong to different generations. Steward was born in Ohio in 1909, Yeomans in 1938 in a small town on the central Florida coast, from which, once he’d gone to college, he kept running as far as he could—first to Atlanta, where he found work as an actor, director, fashion model, and ultimately as the man in charge of the windows at a department store called Rich’s, and then as a member of LaMaMa, the experimental theatre company on New York’s Lower East Side.

In New York, Yeomans encountered not only the theatrical avant-garde but also the world of S/M, which led to a relationship that destabilized his already shaky personality (Yeomans was apparently bipolar), which culminated in a nervous breakdown that sent him back to Florida and his mother, and the small town whose conservative values he had fled. But it was there that he began writing the plays that are his claim to fame—particularly Richmond Jim (the initiation of a young man into S/M), and Sunsets (lost souls in a men’s room on a Florida beach). These were first produced by a gay theatre group in San Francisco called Theatre Rhinoceros, which is what drew him to that city, along with a friendship with the playwright Robert Chesley (Jerker, Night Sweats)—a welcome bond, since Cal’s earlier attempt to befriend the writer James Purdy in Brooklyn had been a disaster. Then, learning that his mother was ill, he returned to Florida. After her death and an attempt to revive his theatrical career that went nowhere, he took up photography before returning to New York in order to get medical care for HIV, and then moved part time to Amsterdam because euthanasia was available there. However, he ended up dying of a heart attack in New York while being prepared for an operation for a congenital heart problem.

Those are the facts, which, however interesting, still leave us with the question raised by this new book, Robert Schanke’s Queer Theatre and the Legacy of Cal Yeomans: why are we reading about this man? Two reasons: the voluminous papers and photographs Yeomans left to the University of Florida provide the material that makes a biography possible; and the fact that sometimes gay history is most vividly brought to life in the stories of minor artists. Yeomans’s life is the saga of a man who grew up in a small town and came out at a time when many gay people were flocking to the cities to be free, where they collided with certain difficulties, not least of them the relationship between sex and the rest of life.

Sex was as crucial to Yeomans as it was to Steward—“one of the great mysteries & motivators of life,” he wrote to a friend offended by the frankness of one of his plays, “filled with humor & splendor & pathos.” At the same time, he knew an opportunity when he saw one. “So many gay theatres opening,” he wrote to a fellow playwright, “that I do advise you to go gay quick if you want to get put on. I stay busy submitting all my old homersexual gay plays that used to be sneered at by various cunts like the WPA. … So thus we begin the 80’s which is the first decade in recorded history when it is anywhere near o.k. to suck dick. Praise God Almighty, free at last! … Wonder if Ellen’s ready?” Ellen was Ellen Stewart, the founder of LaMaMa, a woman with whom Cal had what could be called a complicated relationship, which might be summed up with the words she whispered in his ear even before the applause had died down after Cal had read what he called his Daddy Poems at his failed comeback in New York: “Some beautiful images, but the subject matter: No.”

Yeomans was a writer, however, who saw no difference between his art and his life, a man who, though fully aware of the embarrassment he caused others—and himself—by writing what he did, seems to have been compelled to say things that were forbidden. The Florida town in which he grew up—where his childhood seems to have been a blend of Eudora Welty and William Faulkner—demanded he be Christian and straight. Now he wanted to portray his gay life as it was. Ellen Stewart was not the only person who found this distasteful: the actress Dana Ivey, whom Cal had known since their days in Atlanta, found Cal’s plays equally off-putting. Even the gay theatre community was reluctant to put them on.

It’s no surprise that Yeomans, who directed Harvey Fierstein in a play that was his first assignment at LaMaMa, did not think much of Torch Song Trilogy when it came along. It was, he wrote to the playwright Robert Patrick, “nothing but a quagmire of sentimentality, an Okefenokee Swamp of the trite and sappy. Oh well … they would lock us ALL up if I was telling it like it is.” Angels in America he walked out on at first intermission, later writing to a friend: “stereotypical Aunt Jemima patronization of the suffering of a people. Not since Torch Song Trilogy has any play pandered to the hetero power structure with such fatuity and sure knowledge of what it takes to please a society eager to expiate their real human rights abuses with tokens of liberal acceptance and apology—but with no real effort to accept and understand our culture as it really is.” Or, as he put it in a letter to Dana Ivey: “Tripe. One more rip-off scam night in the theatre. Hokum. Malarkey. Bat crap. Another coffin nail for a dying art.” One wonders why he got so worked up; it’s tempting to think Schanke is right when he appends: “Such harsh reaction to the acclaimed play perhaps revealed Cal’s jealousy and resentment that his plays had never been as successful.” It may also have been because they fell short of what he was after in his own work.

What was he after? Of his own work’s reaching the stage he eventually despaired; his chief outlet became his journal, now at the University of Florida. Yeoman’s journal shows, the way Steward’s did, that a minor artist, an obscure life, sometimes reflects the issues gay people face even more starkly than the famous can. The discomfort Yeomans always seemed to feel in his own skin—the guilt, the sense of worthlessness—may be one that many gay people carry, but rarely has it been expressed as vividly as it was in his journal. Like many of us, Yeomans found it difficult to combine love and sex in the same person for very long; nor did it take him long, after coming out, to see the predatory aspects of what is called making love: “He may rob me, he may kill me, but until then I drink of his young virility & sap his manhood. I steal all I can as I have none myself. I suck it from him & violate his body in total hatred.” But after using someone else as “our toy, our object of amusement,” he thinks: “I longed, somewhere in my deepest being, for a bit of a touch, of a gentle hand, a kiss.”

Yet he never gave up his belief in sex, which meant that AIDS was both a physical and ideological blow that not only made his plays, which had finally begun to gain notice, suddenly undesirable (gay theaters were not looking for anything celebrating sex in 1985), but led, when he himself was diagnosed, to even more self-loathing. “Look at this body” is an entry that appears after a bout of shingles, skin cancers, pneumonia, and a detached retina. “Look at it! I have to live in this 1/2 dead, mangled corpse. This mutilated, scarred, putrid carcass.” HIV was the ultimate insult. “There is no place or function for me on this earth,” he confided to his journal. “My birth seems a mistake. My death will be a relief.” Finally: “I was born at the wrong place at the wrong time in the wrong body to the wrong family.”

The sense of having disappointed everyone plagued Yeomans long before the plague itself, however, which is one reason his biography is so moving. “One of the great sadnesses of my life,” he wrote to Robert Chesley’s mother after Chesley died of AIDS, “is that I was unable to share my little successes in the theatre with my mother. … She could never bring herself to talk about any aspect of sexuality let alone the homosexuality that is rampant in my plays and in my life. Therefore, in a life that has been noteworthy mostly for its failures, I never could say, ‘Look! I did this in gay theatre. Now that’s something, isn’t it?’” Schanke’s biography would be riveting if it were only the story of a relationship between mother and son.

And yet, though Queer Theatre and the Legacy of Cal Yeomans contains so many issues all gay people face that it amounts to a representative life, I doubt that Schanke’s biography will get the attention that Justin Spring’s did. For one thing, Secret Historian was published at an accessible price, while Yeomans’ (at $85) is apparently directed at theatre collections of university libraries. But it’s an absorbing gay history—psychological, social, sexual, and cultural—expertly informed by Schanke’s knowledge of the theatre.

I say this, however, hoping I can be objective—because there is, for this reviewer, one other difference between this book and Secret Historian: I knew its subject. We met in 1983 in a gay bar in Gainesville, Florida, and remained friends for almost twenty years. I couldn’t believe I’d found someone so similar to myself—a gay writer whose life was divided between Florida and New York, where, I learned, we had been living only a few blocks apart. There are things about Cal I did not find in his biography—how could any biographer get everything? But these are far outnumbered by the revelations. I did not know that growing up Cal slept in the same bed as his mother and his father, who would get up and walk around to make love to his mother while Cal lay there, or that Cal’s father chewed tobacco as he drove the family car, spitting it out so that it splattered his wife and son sitting in the back seat. Nor did I know just what Cal meant when he would say, “I left Manhattan on a stretcher.” He meant his nervous breakdown, which Schanke describes with pitiless specificity.

As for the sound of the subject’s voice, the charm, the gestures, the fear a lot of us had of Cal’s “lethal” tongue, his love of life, his unpredictability, what can one say? The printed word abstracts. Biographies are like mummies: in exchange for permanence, the vital fluids are removed. Fortunately, Cal’s gift was verbal, which means the journals and letters Schanke uses capture him well—like the diary May Sarton kept in her old age that Cal so admired. Then there is the fact that Cal seems to have gone through the mill of gay life as few people did.

Schanke (whose previous subjects include Mercedes de Acosta and Eva Le Gallienne) has used Cal’s plays, journals, and letters, plus the interviews he conducted with Cal’s friends, and put them together in unobtrusive, readable prose—and got it right. This book is not just about gay theatre and gay liberation, but also about gay childhood in the small-town South and gay adulthood in cities at a time when liberation turned to horror. It’s an amazing story. There is something heroic, if not tragic, in it, which I did not see at the time, perhaps because in life Cal was nothing if not a lot of fun. “Cooked Down to Nothing” was the title, he used to joke, that he wanted for his autobiography; but Schanke’s book is the opposite. Short of having known Cal Yeomans, this is the closest one can come.

Andrew Holleran’s latest book is Chronicle of a Plague, Revisited: AIDS and Its Aftermath.