My 1980s and Other Essays

My 1980s and Other Essays

by Wayne Koestenbaum

Farrar, Straus and Giroux

336 pages, $16.

WE ARE LIVING in the golden age of outtakes. Edited-out bloopers are for many as interesting as a finished work, maybe even more interesting. No contemporary writer better captures this fascination with the misgivings or second thoughts that occur in the creative process than Wayne Koestenbaum, as evidenced by this new collection of essays, most of which were written in the last ten years. “Too many of these sentences begin with the first person singular pronoun,” he writes a few paragraphs into the title essay. “Later I may jazz up the syntax, falsify it.” This verbal equivalent of cracking up on camera serves a number of purposes. It lets the reader know that Koestenbaum knows that he’s performing on the page. The self-deprecating humor deflects criticism. And it reinforces a point this writer has made many times: the act of writing, as much as the content, supplies the meaning. This book is the work of a serious and vastly well-read intellectual. But due to the outtake poetics, the essays are never ponderous and always fun to read.

The essays are grouped by subject matter—personal history, writers, iconic movie stars, artists—but autobiographical elements appear in so many that the collection is surprisingly unified. Koestenbaum has a postmodern concept of autobiography. There is no narrative, no connection between events, no outcome. In the essay “My 1980s,” he simply presents facts from a decade of his life: people he met, books he read, music he heard. “Does any of this information matter?” he asks, without providing an answer. The significance lies in the emotional impact the essay has on the reader, who begins to recall his own past, realizing that all of our lives are a series of disconnected moments, some of which inexplicably linger in memory long after they are over. As a writer, Koestenbaum has an uncanny ability to engage his readers in this way.

Other autobiographical essays—“Heidegger’s Mistress,” “Anna Moffo’s Funeral”—with their short, numbered paragraphs that jump from fact to fact, resemble lists. Into the mix of philosophers, composers, and opera singers who appear in these essays, Koestenbaum interjects his persona, a skinny young man with no hair on his chest, suffering from “sissy shame” as he tries to score with men and become a writer. He berates himself, he maintains, to make the reader feel superior—and, as a result, pay more attention to life’s nuances, ironies, and pleasures.

The book also contains tributes to major influences on Koestenbaum: Susan Sontag, Roland Barthes, Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick. To help readers understand these complex thinkers, he uses a rhetorical strategy that balances the often abstract content of their work with the casual, slightly irreverent components of his life. Sontag “ate the world.” Barthes had a “cruiser’s mentality.” Neither Barthes nor Walter Benjamin “had a gym body.” Listening to Sedgwick give a talk, Koestenbaum “felt stoned on the cannabis of her smartness.” Queer theorists taught Koestenbaum to resist repressive doctrine and embrace alternatives. His method of thanking them in these essays teaches us the same lesson.

For Koestenbaum, intellectual engagement with a writer always becomes a personal engagement, as is demonstrated in the essays on the gay poets Hart Crane, Frank O’Hara, John Ashbery, and James Schuyler. “Frank O’Hara’s Excitement” is a vivid exploration of the poet’s famous verbal and personal energy. The essay’s excited prose mimics O’Hara’s excited poetry. The long essay on Schuyler is a moving attempt to make this “minor” poet better known. Koestenbaum, an English professor and poet, brilliantly elucidates how line breaks are at the heart of Schuyler’s poetics, to which he’s drawn because the poet was gay, ignored by critics, and receptive to failure.

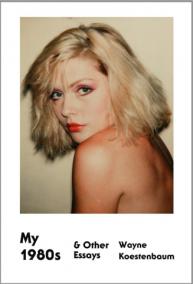

Receptivity to failure is the survival strategy of the legendary ladies that appear so frequently in Koestenbaum’s writings. Elsewhere he has written about Judy Garland and Liza Minnelli. Here we have essays on Lana Turner, whose life became as melodramatic as her movies; Brigitte Bardot, a “washout” and a star at the same time; Susan Hayward, whose gas chamber execution at the end of I Want to Live epitomized the confinement and exploitation of female stardom; and Debbie Harry, who survives her fame and beauty as she shops in the supermarket. Koestenbaum admires the way these women take revenge—often through public failure or personal distance from the circumstances of their celebrity—on the systems that exploit them. This is a theme that resonates with gay readers.

Receptivity to failure is the survival strategy of the legendary ladies that appear so frequently in Koestenbaum’s writings. Elsewhere he has written about Judy Garland and Liza Minnelli. Here we have essays on Lana Turner, whose life became as melodramatic as her movies; Brigitte Bardot, a “washout” and a star at the same time; Susan Hayward, whose gas chamber execution at the end of I Want to Live epitomized the confinement and exploitation of female stardom; and Debbie Harry, who survives her fame and beauty as she shops in the supermarket. Koestenbaum admires the way these women take revenge—often through public failure or personal distance from the circumstances of their celebrity—on the systems that exploit them. This is a theme that resonates with gay readers.

Koestenbaum, whose interests seem limitless, includes ten essays on contemporary artists, many occasioned by gallery shows in New York. Fortunately, readers who live elsewhere have the Internet, where the videos of Ryan Trecartin, the photographs of Paul Mpagi Sepuya, Cindy Sherman and Diane Arbus, and the paintings of Glenn Ligon and Forrest Bess can be viewed. Koestenbaum pulls us into and takes us out of his writing in many ways. His love of words (“oneiric,” “gamelan,” “catatonia” appear in the space of a few pages) sends us to the dictionary. His careful attention to the nuances of his experiences invites us to be more aware of our own moments in life. And his misgivings about his abilities—despite his enormous gifts as a writer and thinker—put us at ease as we enjoy the many pleasures of these essays.

Daniel Burr is an assistant dean at the University of Cincinnati College of Medicine, where he also teaches in the medical humanities program.