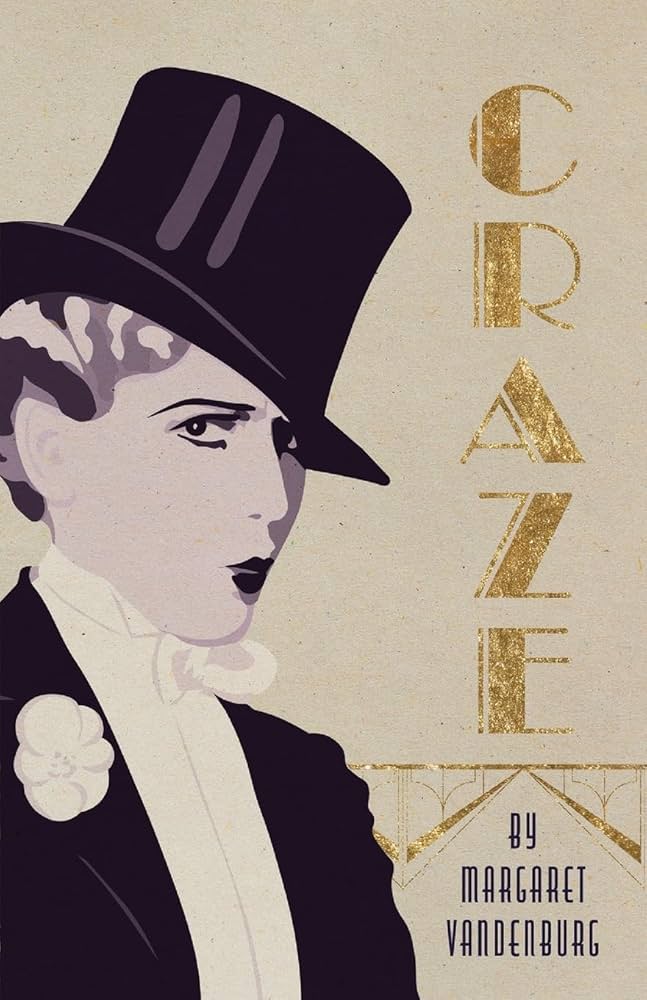

CRAZE

CRAZE

by Margaret Vandenburg

Jaded Ibis Press. 248 pages, $17.99

THE PREFACE to Margaret Vandenburg’s latest novel, Craze, is the opening paragraphs of a 1933 article in the weekly tabloid Broadway Brevities under the headline: “6,000 Crowd Huge Hall as Queer Men and Women Dance at 64th Annual Masquerade.” The article goes on: “Queer people … are increasing. Dances are their big social events. … Most of the ‘women’ in attendance at the orgies are men in disguise. The majority of the people in tuxedoes are female.”

This introductory material promises a rollicking, rowdy, colorful tour of speakeasys and balls crowded with queer people living through the Prohibition and Depression eras in New York City—a promise that the novel mostly fulfills. The “Craze” referenced in the title is, the narrator explains, the “queer craze” that coincided with the “Jazz Age,” known for speakeasys, the Harlem Renaissance, clandestine mob-owned gay bars, and huge balls where drag kings and queens rubbed shoulders with the hoi polloi and “slummers,” i.e., New York’s rich movers and shakers out sampling forbidden pleasures. “We accommodated ourselves,” Henri says, “to a world that largely left us alone.”

The narrator, Henri (short for Henrietta) Adams, is an art critic who has just arrived in New York City from Paris. A native of Bliss, Utah, with a rather dreadful, repressive family from which she always felt apart, she declares: “I was born in the wrong place, if not the wrong time, a cockatoo hatched in a sparrow’s nest.” She fled to Paris after college for freedom and a writing career at a French art magazine. Upon her return to the States, with a letter of introduction from Ernest Hemingway (whom she befriended at Gertrude Stein’s salon), she quickly lands a job writing for the rather stodgy New World Art magazine. There she makes it her purpose to introduce more modern and contemporary artists, which leads her to conduct interviews with Frank Stella, Georgia O’Keeffe, and other art world luminaries. Whether on assignment or at the magazine’s office, Henri presents the “appropriate” dress and behavior for her sex—A-line skirts, starched blouses, a string of pearls—and “passes” in the straight, white, male-dominated work world. The first person with whom Henri chats at length is a tall, thin, effeminate man sitting on their boardinghouse stoop, who introduces himself as “Crystal, the Queen of Tarts.” The two become instant friends and confidants, and Henri is welcomed into Crystal’s circle of friends. At night, the Henrietta who dresses in skirts and pearls by day becomes Henri, the self-declared “bulldagger” lesbian out prowling for “violets,” preferably younger and blond. The plot is fairly simple—girl meets girl, girl meets another girl and loses track of the first, girl eventually returns to the first girl. The latter is a severe-looking, leather-clad “dagger” who corners Henri in the hallway outside the bathroom. The bartender warns Henri that “That woman is trouble,” as befits her nickname, “the Python.” Although the Python stays on Henri’s mind, the two don’t meet again for some time. The second woman is Constance, a fabulously wealthy married woman living in a large apartment on the Upper East Side. Their affair progresses from secretive daytime romps in Constance’s apartment to forays into the queer underworld guided by Henri. Their affair lasts a couple of years but fades away. When Henri meets the Python again, whose real name is Joan, she meets a cultured, thoughtful woman who gives off the opposite impression to the one that Python gave off at the bars. The Great Depression brings about not only economic misery but also a reactionary return to the enforcement of “morals” laws and an open season on queer businesses. After a violent police raid at Frank’s Place during a drag king and queen competition, Henri reflects: “Silly us. It turned out the police raid was a harbinger of things to come, the crest of the first wave of a systematic crackdown that would sound the death knell of the Craze.” There is much to be applauded in this novel. The third chapter is a delicious rendering of one of Henri’s return visits to her family in Bliss. Her very conservative religious parents, including her passive-aggressive mother and her sympathetic younger sister Melanie, all come to vivid life. This glimpse of Henri’s home life amplifies the extent of her rebellion against it. Later, Henri muses on the labels by which various groups in the queer world were identified: “jams” for straight people; “violets” for femme lesbians; “bulldaggers” for their butch lesbians; “pansies” for effeminate gay men; “queer” for the men who eschewed the effeminacy of the pansies. She muses on the idea of naming as identity: “[W]e started to think of ourselves as a united front, not just a loose collection of parallel predilections. We were a work in progress, in a way, exploring the linguistic parameters of who we might become.” One thing I found off-putting about Craze involves that tabloid article preface. That promise of a rowdy, colorful trip through New York’s underworld isn’t quite fulfilled. There is scant description of the speakeasys as physical spaces where the characters meet and interact. The view is somehow vague, gauzy, as through a glass darkly. The characters themselves are described in cursory fashion, so it’s not even clear what they look like. But aside for this minor criticism, Craze a highly readable, sexy, entertaining look at queer life, lust, and love in a bygone era.

Hank Trout, a frequent contributor to these pages, is the former editor of A&U: America’s AIDS Magazine.