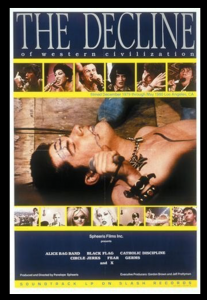

THIS SEPTEMBER marks what would have been the sixtieth birthday of punk musician and Germs front man Darby Crash. As a musician, Darby was active for only a short time, leaving few artifacts beyond an album and a few memorable performances in Penelope Spheeris’ film The Decline of Western Civilization, about the underground music scene in Los Angeles. Darby died in 1980 at the age of 22.

It is sort of impossible even to picture what he might be like at sixty years old, so determined did he seem to embody the “live fast and die young” punk ethos. Maybe he would have gone on to a longer career of continual musical invention like Madonna, Michael Jackson, Joan Jett, and Prince—all born in the same year (1958)—but I doubt it. Darby enacted the script of his own five-year plan, one ending with his intentional death and pursuit of immortality.

I first learned about him through a song called “Homosexual” by the Angry Samoans. Appearing on a 1982 classic punk record, the song is not meant as a positive gay anthem. For me, however, discovering the song years later, there was—and remains—something so subversive and boldly free about the way they keep shouting “homosexual!” In the song, there was one name just dropped in without explanation, a wink to others in the know: that of Darby Crash.

Obviously, for them this was meant to be a pejorative association. For me it was a signpost. As I learned more, I would come to be preoccupied with both the music (aggressive and hard driving) and Darby the performer. Darby embodied the carnivalesque spirit of a world turned upside down. His performativity can be read as an æsthetic strategy as much as the exercise of a tragic and tormented life. The drugs and the drinking himself to oblivion, the resulting physicality on stage, his fighting and passing out, the sex with men and the terror of being found out, the poetic lyrics and often unintelligible delivery of them, the persona constructed through an intentional bricolage (an assemblage of David Bowie and Iggy Pop, among others)—all became interwoven in his unique queer grotesquerie.

In Modern Art and the Grotesque (2009), Frances Connelly remarks that the mode of expression known as the grotesque, “whether subversive, comic, abject, wondrous, or caricatural, is at once a profoundly destructive and creative force.” The idiosyncrasies of Darby’s life and art illustrate the ongoing pursuit of just such a force. With Darby, it is hard to see where one begins and the other ends; indeed, Darby’s has always been a circular performativity. In life and in memory, he remains fluid: comic and disgusting, an original and a copy, a pioneer and a cliché, a fixed memory and a future invention, an unknown and a cult hero.

He was preoccupied with the theatricality of the circle, and the blue circle on black background became both the band’s logo and the cover of their only official album. I’m sure he would appreciate the wide turn his circle has made, from the gay signifier in a homophobic song to a cultural commodity. The past ten years have seen increased attention to Darby, including scholarship (Jose Esteban Muñoz, among others), a 2008 feature film, a related band reunion (with actor Shane West standing in for Darby on stage), and a Shepard Fairey mural in the Silver Lake neighborhood of L.A.

It seems to me that much of the scaffolding of this popularity is based on Darby’s sexuality: Darby the queer kid reclaimed. While in life he was terrified of being outed, our contemporary reading of Darby allows us to connect his particularity to a wider narrative of ongoing queer culture, past and present. In the process we reframe him outside of the closet, with his gayness front and center. I am glad that we are able to know Darby as gay and hope that other gay kids who are discovering alternative music will find him to be an interesting point of consideration, their own possible signpost.

In this way Darby achieves some of the immortality for which his five-year plan was designed. He had an eye on this during his short life, instituting the tradition of the Germs burn: the scar left by a cigarette put out on the bone of the left wrist. The idea was that this deforming sign could be recognized years later, handed down, as it were, from person to person, like a sacred initiation rite. Darby’s intentional death by heroin overdose was another example of a grotesque pageant designed for immortality and was both overshadowed and heightened by its macabre and unplanned alignment with the murder of John Lennon on the opposite coast.

It is probably his element of grotesquerie that has been most gentrified. Darby as a mural on the wall in a hot neighborhood gestures to his transgressive art, life, and sexuality without all the complications of his narcissistic personality, destructive behavior, or the queer oppression he experienced and feared. No longer does he stand in opposition to the conventional concept of beauty; in many ways he represents it. Indeed, Darby Crash at sixty is in good shape: a young, good-looking, white, queer, skate punk, right at home in any number of 2018’s cultural spheres. Dislodged from the messiness of his own context, Darby is a welcome addition to our own.

Philip Moore is a doctoral candidate at Gratz College in Melrose Park, PA.