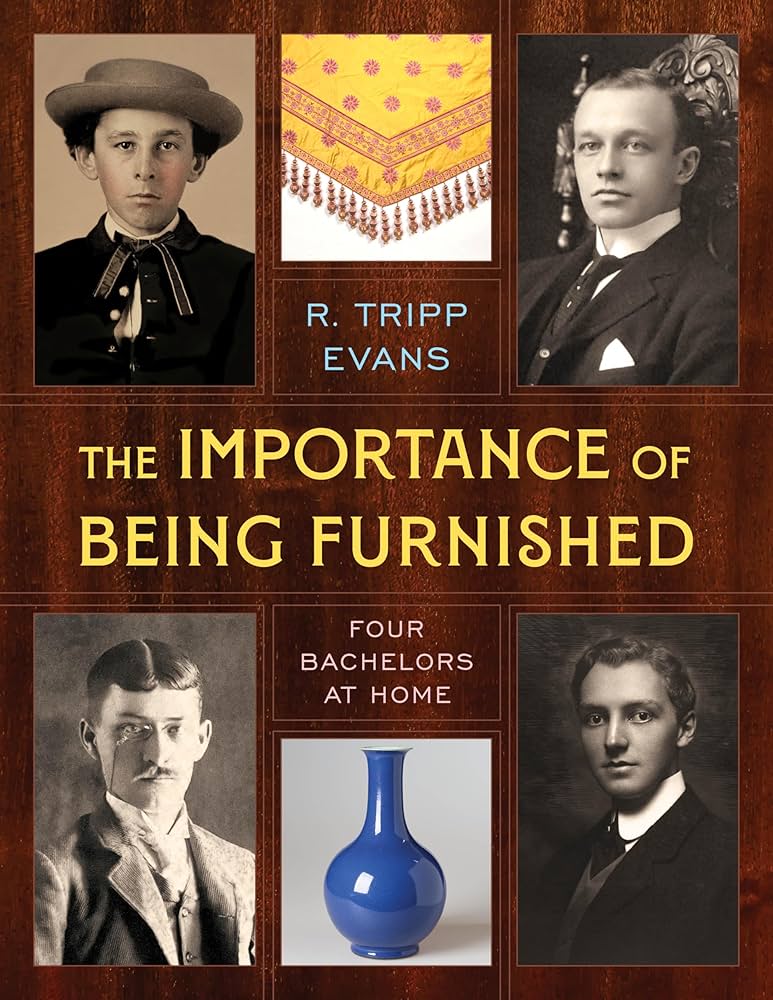

THE IMPORTANCE OF BEING FURNISHED

THE IMPORTANCE OF BEING FURNISHED

Four Bachelors at Home

by R. Tripp Evans

Rowman & Littlefield

202 pages, $45.

WITH A WINK to Oscar Wilde, R. Tripp Evans’ The Importance of Being Furnished celebrates four influential Americans—Charles Leonard Pendleton (1846–1904), Ogden Codman Jr. (1863–1951), Charles Hammond Gibson Jr. (1874–1954), and Henry Davis Sleeper (1878–1934)—whose imaginative houses, now public museums, marked a pivotal shift toward personal expression in home design.

Urban expansion and the rejection of Victorian ideals gave rise to the social phenomenon of “the bachelor.” Oscar Wilde, in keeping with the Æsthetic Movement’s ethos of “art for art’s sake,” championed interior design as a pursuit uniquely suited to “the single man of means.” While a handsome home conferred social status, it also offered opportunities for veiled signals of identity. The desire for sexual conquest was sometimes transferred to the acquisition of exquisite objects.

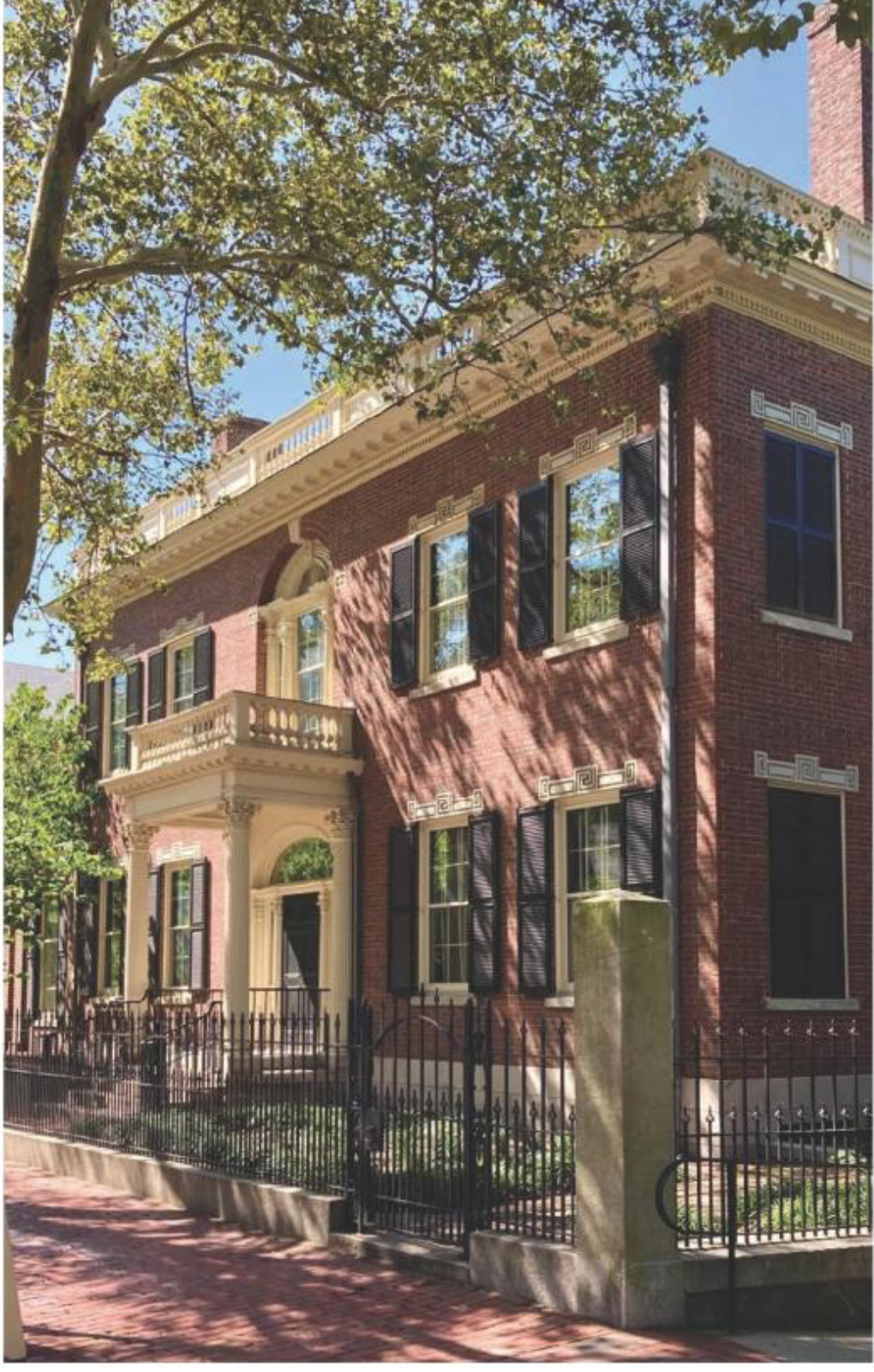

The reclusive Pendleton’s commitment to collecting overrode any concern for practicality. His rented Georgian-style home, described as “a shrine to beauty, not to hospitality,” was crowded with a “staggering” collection of tea services and other fine examples of American and European furnishings. He was particularly obsessed with Chippendale furniture. Evans’ drooling description of the style—“muscular carving … widespread legs … the phallic form of its sturdy cabriole supports”—makes clear how objects could be sexualized. An avid gambler, Pendleton regarded his furnishings as assets, selling them as needed to fuel his habit. He died in debt, bequeathing his collection to the Rhode Island School of Design Museum. The circa 1799 house that bears his name is a reproduction of a house he didn’t even own.

In 1897, Codman collaborated with Edith Wharton on the seminal design tome The Decoration of Houses, which has never been out of print. His love for “the vanished world of his childhood” impelled him to take possession of his circa 1740 childhood home in Lincoln, Massachusetts. Even during a long European exile, he vastly expanded the house, endowing its interiors with a French-inspired elegance that allowed “any degree of illusion as long as it pleased the eye.” In letters, Codman was open about his attraction to men, explaining to his mother that he’d skipped a beach trip because “the Boys are not very attractive.”

Once effectively banned from his family’s 1859 Boston rowhouse, Gibson, upon inheriting it, reimagined it as a shrine, first to his beloved mother (who had enlisted Codman’s decorating help and with whom Gibson had a “disordered” relationship), and later to his own youth. (Architect Arthur Little called him “the juiciest looking boy I ever saw.”) Destitute in old age, Gibson recast the house’s tattered furniture and moth-eaten carpets not as things worn down by time but as a stage-like set for its eccentric poet-in-residence (himself), almost as an act of performance art. He secured the home’s preservation in part by creating a detailed and elaborate registry of its many furnishings, sometimes fabricating backstories about their provenance and inflating their value, fooling few but convincing enough to prevent their sale, preserving them as a fascinating time capsule.

Sleeper’s 1907 Arts and Crafts home, known as Beauport, in Gloucester, Massachusetts, stands as a monument to his unrequited feelings for the boy next door. Infatuated with Harvard professor A. Piatt Andrew, Sleeper acquired a harbor-front property nearby. Alas, Sleeper was not Andrew’s type. This did not stop Sleeper from writing several times a week and smothering Andrew with gratitude for any look that came his way. Realizing that “the novelty of his home … held Andrew’s attention,” he never stopped working on it. The kooky additions by the inexperienced architect Sleeper commissioned turned Beauport into an enchanting, larger-than-life cottage whose maze of themed rooms still retains its magical charm today.

Evans, a professor of art history at Wheaton College, brings deep expertise to his subject. While his writing is sometimes overblown—“But what becomes of the profound joys and wicked disappointments, the thrill of ambition and the rage of loss, the triumphant pride and haunting shame that once roiled inside their walls?”—his passion is admirable. The book’s many photographs convey more historical information than atmosphere, supporting its role as a reference guide for serious study.

Michael Quinn writes about books in a monthly column for the Brooklyn newspaper The Red Hook Star-Revue and on his website, mastermichaelquinn.com.