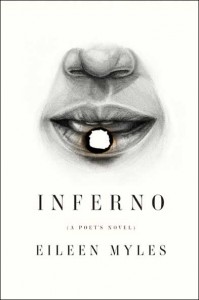

Inferno (A Poet’s Novel)

Inferno (A Poet’s Novel)

by Eileen Myles

OR Books. 244 pages, $16.

HERE IS A BOOK that interweaves fiction, social commentary, history, and satire. Eileen Myles’ Inferno offers different attractions to different readers: some will read it for its story about how to become a poet; some will be enthralled by its imaginative history of New York in the 1970’s; some will focus on the sex; and some will pick it up solely for the author’s name on the cover. None will be disappointed.

The book can be seen in part as the stylized ramblings of a narrator coming into adulthood in New York in the 70’s. The novel opens with the narrator commenting that “My English professor’s ass was so beautiful.” Throughout the book, she relates various escapades involving work, sex, and survival. Readers might conclude from this description that Inferno is a “coming of age” or “coming out” story, but the book addresses many other topics while hitting some of the high points in its author’s distinguished career. Some of this material may be related to the fact that parts of the book were written as a grant application to the fictional Ferdinand Foundation. Myles also uses the occasion to poke fun at the system of arts funding, and includes digressions in the application that relate only tangentially to her memoir. Anyone looking to learn about her full body of work by reading Inferno will be disappointed.

The book also traces Myles’ development as a poet, examining her relationship to poetry groups in New York, especially the St. Mark’s Poetry Project. In addition, poets like Hart Crane, Robert Creeley, Alice Notley, and others figure prominently as influences in the development of her own thinking and writing. These teachers and heroes she presents with all of their quirks and flaws rather as paragons. In fact, one of her poems, “On the Death of Robert Lowell,” includes the thought that “The guy was a loon,” among other provocations. Myles takes great interest in noticing how iconic figures can be dismantled, going so far as to do some dismantling of her own.

While Inferno might be considered a feminist or lesbian book, Myles resists this kind of labeling. Remembering several lesbian poetry magazines of the 70’s, she remarks that “clearly it was a trickle and it might dry up. You didn’t want to get caught there.” Later she writes: “The feminists seemed so serious, even when it was about sex. They taught in college and seemed rich. They just weren’t hip.” It is ironic then, that many of today’s feminists study and revere Myles as a feminist icon. And while she may have a complicated relationship to feminism, she seems much more comfortable with the label “lesbian” or “queer,” and takes great pleasure in discussing her relationships with other women, recounting not only passionate love scenes but also domestic life with her various partners.

The breathtaking scope of Inferno makes for difficult, even unwieldy, reading at times. There are moments when Myles’ attention changes from page to page, and it can be difficult to keep track of the large, ever changing cast of characters. Yet the sheer ambition of the book will keep the reader’s attention. With moments of extraordinary imagination and insight, Inferno is not only an important contribution to Myles’ body of work but also to lesbian literature and to the growing memoir genre.