The Lost Autobiography of Samuel Steward

The Lost Autobiography of Samuel Steward

Edited by Jeremy Mulderig

U. of Chicago Press. 274 pages, $30.

IN 2011, Justin Spring’s award-winning biography, Secret Historian (reviewed in the November-December 2010 issue of this magazine), brought to light the curious history of Samuel Steward. Steward was a former Loyola and DePaul University professor turned professional tattoo artist—a life change that was unusual enough. But it was his history as a sexual renegade, and his long-time collaboration with Alfred Kinsey on the famous Kinsey Report, that constitute his legitimate claim to fame—and the fact that he wrote a great deal of gay literature under the name of Phil Andros. Oh, and then there’s the fact that he had sex 4,647 times with over 800 different men, including Rudolph Valentino, Rock Hudson (in an elevator in Marshall Field’s department store), Lord Alfred Douglas (Oscar Wilde’s young lover, who lived until 1945), and Thornton Wilder. He also maintained friendships with Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas, André Gide, and a host of other luminaries.

Born in Ohio in 1909 and living long enough to touch upon every decade of the last century, Steward seems to have been unapologetic—even defiant—about his sexuality right from the start, professing to have had sex with every member of his high school basketball team, four members of the football team, and three on the track squad. Nor, he claims, was he ever taunted for this—partly, he reasons, because the men he seduced enjoyed access to sex too much to complain, and also because of the relative lack of sophistication of people in small towns: “By and large, homosexuality and fellatio were considered so unbelievable and impossible that although one might be teased for being a sissy, no one could believe that any person actually engaged in the ‘abominable sin.’ This kind of thinking protected us all during the 1920s and ‘30s, and we lived happily under its shadow and cover.”

Steward was a meticulous record keeper who began right from the start to keep a file detailing every sexual encounter he ever had.

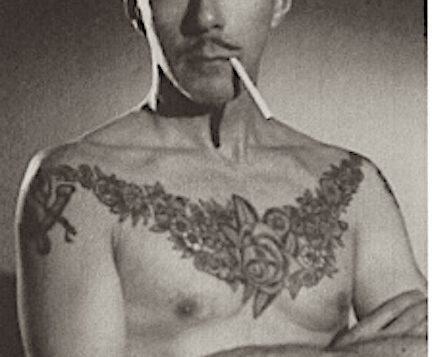

After the shock at the number and variety of his sexual partners wears off, what stands out is Steward’s sheer unwillingness to let anyone else dictate how he was going to live his life. Even as a young doctoral candidate, he very daringly touched upon Whitman’s “Calamus” poems (the ones with overt homosexual content) in his thesis, and also argued that Cardinal Newman was probably gay. This created no small buzz in the English Department, of course, but despite this controversy he was awarded his doctorate and was eventually able to teach at both Loyola and DePaul Universities in Chicago, where he would remain for twenty years. Even while teaching, however, he was continually exploring Chicago’s gay milieu, so his book offers a wealth of information about Chicago’s gay past, from the fact that gay men cruised at Oak Street beach and tangled at Foster Avenue, to the fact that in 1950s-era Chicago—before there were gay bars—the opportunity for sex “was largely a matter of apartment living and apartment encounters.” Even his eventual decision to leave teaching was an act of thumbing his nose at society. As he was going out the door, he had his chest tattooed with a winged phallus and whip, thereby literally branding himself, à la Hester Prynne in The Scarlet Letter, with an emblem of sexual defiance.

Friends and family were aghast at his career choice, of course, but he wore his tattoos—and viewed his tattooing—not only as a badge of honor, but also as an assertion of sexual freedom. It was also risky. If anyone had caught sight of his tattoos—not to mention the erotic and very explicit illustrations on the walls of his home, or his extensive private collection of gay erotica—he might have been immediately arrested and thrown into jail. This possibility did not, however, deter him from his chosen course. In fact, it may have been what spurred him on. Poet and writer Glenway Wescott recounted a conversation in which he asked Steward, “Aren’t you running a frightful risk?” Steward’s answer: “Of course I wouldn’t dare do it, except that my dream all my life has been to be in prison, and to be fucked morning, noon and night by everyone, and beaten.”

Eventually, Steward met Kinsey, who was immediately impressed not only by Steward’s sense of liberation about sex but also by his immaculate record keeping. Over time, Kinsey filmed him in several S/M sessions, and the two of them spent over 700 hours discussing such things as the link between tattooing and sex (both involve an active and a passive partner, as well as insertion). Steward’s life as a tattoo artist eventually came to fascinate Kinsey as much as his sex life, even though the unshockable Kinsey disapproved at first of his choice of occupation. The moment he left academia, Steward reveled in his sudden, unfettered access to all the glorious young navy bodies (via Chicago’s close proximity to the Great Lakes Naval Base). He could now freely touch and decorate these men—something he’d never been able to do as a teacher, when all he could do was gaze out at all the bright, young, unavailable male students. Steward writes that many of them opened up in unexpected ways during the sudden intimacy of the tattooing session, and he had sex with a number of them in the back of his shop on Chicago’s skid row (which was located in those days on State Street south of Van Buren).

After fifteen years of this, legal complications arose when the law in Illinois changed at some point, requiring that anyone receiving a tattoo be at least 21. This suddenly dried up Steward’s supply of eager young eighteen-year-olds, forcing Steward to relocate, first to Milwaukee, and then to the far more liberated San Francisco of the late 1960s. However, the reality was that Steward was now aging. Anyone else at this point might have begun to think about retirement, but there was yet a third career in store for Steward, that of a writer of pornographic tales: “To bring pleasure to lonely old men in hotel rooms at night.” Thus was born the literary persona of “Phil Andros” (“love of men” in Greek), who would go on to create a series of hustler stories such as $tud and Below the Belt, graced with covers by Tom of Finland.

All of this material, and more, has already been covered in Spring’s excellent biography—so thoroughly, in fact, that one might wonder at this point: is there really much value to reading the autobiography itself? Spring’s book drew on a great variety of Steward’s unpublished work, as well as notations in his “Stud file.” In the new book, editor Jeremy Mulderig has set himself the task of reconstructing Steward’s autobiography from a vastly truncated earlier work (Chapters from an Autobiography) and from his unpublished, 110,000-word, shapeless manuscript, which is housed in the Beinecke Library at Yale. The result is a reconstructed and expanded version of 85,000 words that has never been published in this form before. It is a thoroughly engaging work in its own right, though there are curious omissions. For example, notes about Steward’s encounters with both Rudolph Valentino and Rock Hudson are frustratingly missing.

Steward is an engaging and erudite writer (his doctoral background is evident), and he offers tantalizing glimpses into such writers as Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas, with whom he carried on a friendship that spanned decades. It also provides fascinating insights into well-known but sadly closeted individuals such as Thornton Wilder, of whom Steward writes: ”Thornton went about sex almost as if he were looking the other way, doing something else, and nothing happened that could be prosecuted anywhere, unless frottage could be called a crime. There was never even any kissing. … He could never forthrightly discuss anything sexual; for him the act itself was quite literally unspeakable.”

Mulderig claims in his introduction that The Lost Autobiography is one of the great queer diaries of the 20th century (one wonders how many of these there actually are; still, the claim does not seem wildly off base). Here is a witness to some of that century’s great personalities, living defiantly through the strictures imposed by society during those times, and asserting at every turn that he had as much right to be happy as anyone else. (He refers at one point to his “happily wasted life.”) Mulderig continues: “It would be inaccurate to say that [Steward] filled his life with ‘meaningless’ sex. Rather, every sexual act had meaning for him because it distanced himself further from the narrowly religious upbringing he had rejected and affirmed the sexuality that was so central to his sense of self.”

Still, one catches glimpses of a fundamental loneliness that even the happily shaped contours of the autobiography cannot hide. Steward’s relentless pursuit of sex seems almost a guarantee of ultimate isolation and, at the end of the autobiography, he has only his dog to comfort him. As Steward writes (in a passage that Mulderig uses as the epigraph for the entire volume): “I did in a sense have an old artichoke heart, and the various pen names I used in the things I wrote, my Sparrow name as a tattoo artist and later the Andros name as a writer, were like separate leaves that are capable of being stripped away. But what was at the center?” Late in the autobiography, Steward continues in this vein: “Had I the capacity for love, or was I inclined to be a solitary with such a poverty of spirit that I could never enlarge myself to take in another?”

Steward seems intent in the Autobiography on the fact that he was happy; and while both Spring and Mulderig are good at pointing out discrepancies between Steward’s somewhat rosy account and other, differing indications elsewhere, can we really doubt his claim? Regardless of what one ultimately decides, his autobiography is one of the most remarkably daring and unusual accounts by an unapologetically renegade gay man of the 20th century.

Dale Boyer is the author of The Dandelion Cloud and Thornton Stories. A new work, Justin and the Magic Stone, is forthcoming.