Just One of the Boys: Female-to-Male Cross-Dressing

Just One of the Boys: Female-to-Male Cross-Dressing

on the American Variety Stage

by Gillian M. Rodger

U. of Illinois Press. 242 pages, $28.

MELISSA MCCARTHY’S Saturday Night Live impression of Sean Spicer (the Trump administration’s first press secretary) was sidesplittingly funny not only because of her incomparable physical comedy, but also thanks to male impersonation as a phenomenon. Kate McKinnon’s equally hilarious SNL impression of Jeff Sessions exploits cross-gender casting to lampoon the effeminate creepiness of the Attorney General. Male-to-female cross dressing has a long tradition in comedy, but its inverse is a welcome addition to the SNL comic armamentarium, particularly during the current hyper-macho Trump administration.

The history of males performing female parts has been well documented, perhaps most famously in Elizabethan theater of Shakespeare’s time. Similarly, in Japanese theater the disrepute of female actresses led to the enduring tradition of the onnagata, which has also been well documented. Since the 1990s, drag kings have attracted much cultural and critical attention as part of a broader efflorescence of queer and trans culture. Much less scholarly attention has been paid to the history of female-to-male performance aside from some icons like Sarah Bernhardt and Marlene Dietrich. Consequently, Gillian Rodger’s Just One of the Boys is a welcome and fascinating addition to the history of cross-dressed performance and 19th-century Anglo-American theater more generally.

Rodger is a professor of musicology and ethnomusicology at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee who specializes in American variety and vaudeville theater. Thanks to meticulous research from dozens of archives, newspapers, and the trade press, Rodger brings to life the careers and lives of scores of English and American women actresses and dancers who performed briefly or for extended periods dressed as men from the 1860s until the turn of the 20th century.

The author is up-front about the fact that she had hoped to document a genealogy for contemporary drag kings rooted in 19th-century American theater. However, female cross-dressing turns out to be a far more discontinuous phenomenon, with drag kings reporting inspiration from 20th-century drag queens and tuxedoed icons like Dietrich or singer Gladys Bentley. But documenting lesbians among the many female cross-dressers of an earlier era proved challenging to Rodger, as it has to many historians of women-loving women in the past. It appears that only one actress publicly acknowledged her marriage to a woman, which in itself was daring for the 19th century. While this may not be a history of lesbian actresses or drag kings, it is a fascinating analysis of gender performance.

Breech or trouser roles (women playing male parts) were common in late 17th-century English theater. Rodger points out that before the English Civil War, some women tackled male roles (like Hamlet) in order to expand their repertoire beyond that of pretty, respectable women or great classic female roles like Lady Macbeth. Eighteenth-century operas increasingly included trouser roles for high vocal parts if castrati were not available. Rodger mainly explores a more challenging historical subject than these high culture performances, since popular theater was less scripted and less documented in reviews than the opera or dramatic theater.

Woven into this history of cross-dressing performance is an equally complex history of popular theater, including music hall, variety shows, burlesque, minstrelsy, and vaudeville. Many vaudeville performers of the early 20th century transitioned from stage and radio to television, including the Marx Brothers, Burns and Allen, and Jack Benny. Mid-century television variety shows were a staple of American culture (for example, Ed Sullivan, Dinah Shore, Lawrence Welk, Frank Sinatra, and later Carol Burnett, Judy Garland, and Sonny & Cher). Spanish-language Sábado Gigante was popular for half a century, and I grew up watching Sábado Sensational in Venezuela, which is still running, even if the country isn’t. Consequently, SNL, with its live mix of musical acts, stand-up comedy, and sketch comedy, has a venerable history.

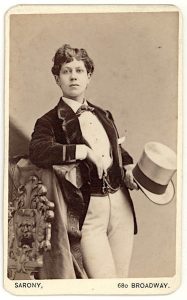

Of course, there were no videos to document variety stage productions, and while popular lyrics and music may have been published, many variety acts involved improvised humor and banter with the audience. Press clippings and publicity materials give us just snippets of the actual performed material, and we have to trust the reviewer’s accuracy or the theater agent’s puffery. Rodger includes several dozen publicity photos of 19th-century actresses, but these provide a very stiff impression given the long exposure times of early photography.

The first male impersonators began appearing on the American variety stage after the Civil War. Some, like Annie Hindle, had emigrated from England after experience in dramatic theater. (Later English performers had experience in the British music hall circuit.) Hindle’s act consisted of quick costume changes while singing in her low alto voice, alternating with comic monologues suited to her male characters from all walks of life. “The Great Hindle,” as she billed herself, was one of the most successful of variety performers. She had a brief and apparently abusive marriage to an English music hall performer. Her published poems suggest that her primary romantic attachments were to women.

Then, in 1886, under the name Charles Hindle, she married her dresser, Annie Ryan, leading to a press scandal and the charge that she had hoodwinked the public about being a male “impersonator.” However, the scandal seems to have been forgotten in a few weeks. Even when a critic mentioned it a year later, it was incidental to his positive review. He describes Hindle as “the only living woman who has a living wife. By every one it was agreed that her appearance was the hit of the olio [a song and dance routine after a dramatic act].” In her publicity shot from the 1880s, she strikes a decidedly butch pose. As Roger points out, male impersonation was also a practical financial adaptation for older actresses who could no longer pull off youthful roles in dramatic or burlesque theater.

Ella Wesner was a Philadelphian who, like many male impersonators, had an early career as a dancer. She diversified her performances as she grew older to include blackface minstrelsy. Her male impersonation act, with song and quick costume changes, was billed as “à la Hindle” and was successful from the East Coast to Texas. Wesner never married. Hindle and Wesner specialized in the song and banter role of the “swell,” who was a wealthy man of leisure. One critic described the swell as “an idler with a snap, a butterfly with some virility.” For the popular, largely male audience, this dandy was simultaneously a figure of humor and of emulation, with his fashionable clothes and wealth that could attract beauties. Although the medical literature of the 1870s had begun describing “sexual inversion” and the popular press was critical of foreign performers with “unnatural passions,” Hindle’s and Wesner’s personal lives were overlooked even as their stage act was wildly popular for its transvestism and its parody of gender-bending masculinity. Perhaps it was similar to the amused cognitive dissonance of the middle-class matrons who were fans of Liberace’s campy performance while still believing he was straight.

Hindle’s success led to a number of imitators in the 1870s, as the new railway system permitted the expansion of variety theater further west, and despite an economic depression linked to speculation on the railroad companies. Variety show managers adapted by trying to expand audiences beyond working-class men, creating respectable programs that would appeal to women and families. Burlesque spectacles, meanwhile, could continue to draw in working men. Class satire seems to have given way in the 1870s to escapist entertainment, with a small number of younger male impersonators with a more feminine appeal.

At the dawn of the 20th century, live popular theater turned further toward respectable, middle-class family fare with the arrival of vaudeville. This development challenged the appeal of male impersonation and brought with it several political developments. The renewed public visibility of women suffragists coincided with concerns about the “New Women,” who demanded equal civil rights and chose career over motherhood and traditional feminine roles.

Vesta Tilley, who transitioned from English music hall to American vaudeville, was one of the most popular and highly-paid male impersonators at this time. Critics praised her refinement and “slender, graceful body” while singing in a soprano voice as a man. She even exploited her high-fashion character to market men’s socks and waistcoats. Yet she explicitly disowned gender bending off stage. In a 1904 article titled “The Mannish Woman” in the Pittsburgh Gazette Home Journal, Tilley wrote: “While my business is that of impersonating male characters, I heartily detest anything mannish in a woman’s private life. … By saying that I object to the mannish woman I mean it in the broadest sense and would have it understood that I refer not only to your Dr. Mary Walker, who wears male attire exclusively, but she who affects the mannish style aping in a degree the various characteristics of the sterner sex. Of the two types I hardly know which is the most objectionable.”

Mary Walker, for her part, was an abolitionist, prohibitionist, and women’s suffragist who served as a surgeon during the Civil War. She is the only woman to have been awarded the U.S. Medal of Honor. Walker lobbied for women’s dress reform and was buried in a black suit. Such gender bending heroics were not to Vesta Tilley’s taste—or simply did not sell vaudeville tickets. The bawdy, butch performance of an Annie Hindle gave way to a reassuringly female male impersonation. By the 1920s, Roger concludes, the whole phenomenon seems to have vanished from American vaudeville, save for exotic, foreign acts. However, even Marlene Dietrich’s iconic appearance in a tailcoat in the film Morocco (1930) was less a performance of male impersonation than a burlesque tease elevated to a singular display of feminine sexuality. An era of male impersonation that poked fun at the dandy for the amusement of working-class men had come to an end, along with a genre of popular live entertainment.

Vernon Rosario is a child psychiatrist with the Los Angeles County Department of Mental Health and an associate clinical professor of psychiatry at UCLA.