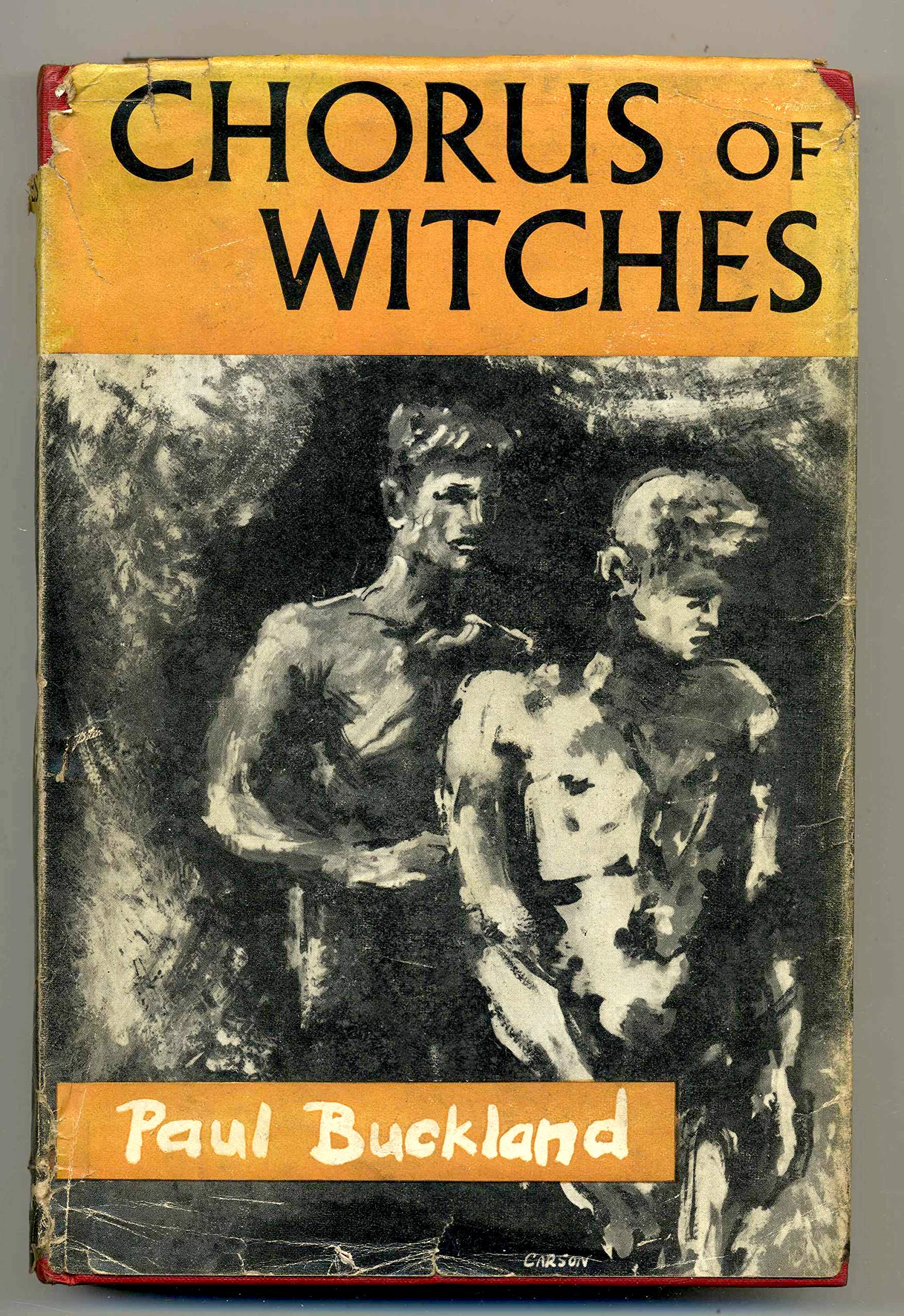

IN ITS ONGOING, heroic effort to bring older gay titles back into print, Valancourt Books sometimes publishes acknowledged classics, like James Purdy’s Narrow Rooms, one of my top choices for the Great Gay Novel, or lesser-known works by significant writers, like The Fall of Valor (which I reviewed in the May-June 2017 issue of these pages), by Charles Jackson, the author of The Lost Weekend. And sometimes, fortunately, it publishes oddities like the 1959 British novel Chorus of Witches, by the otherwise unknown and probably pseudonymous Paul Buckland. By no means great, it is completely enjoyable to read and provides a glimpse into aspects of gay British life over sixty years ago.

Chorus of Witches (a stupid, meaningless title) is set against the background of a traveling female impersonator show, the Merrie Belles, something like the Jewel Box Revue in the U.S., where the “girls” perform vaudeville-style acts and, at the finale, remove their wigs to the delight of the mostly heterosexual audience. Colin, a beautiful twenty-year-old man, joined the troupe to escape from a boring job. In drag, he performs as the target in a knife-throwing act with the butch Scotsman Jock, who’s tormented by unrequited love for Colin. Completing the triangle is Alan, who knew Colin as a boy when he was a soldier during the war and who now, quietly but unequivocally gay, is attracted to the grown-up Colin.

If what I’ve just described sounds like a plot, Chorus of Witches is not in the least plot-driven. The first avowal of love doesn’t come until page 93, and the sense of rivalry appears only on page 138. Instead, the background is very much at the forefront, with the scenes relating to the show tending to overshadow the love story. In a way, the novel feels like two books—one about the female impersonators and their show, and one about the romantic triangle—books that are incompletely merged, with Colin as the link between them. Both books hold real historical interest, while the tension between them is illuminating in its own right.

I can’t vouch for the accuracy of the theater scenes, but the details feel authentic, as when the man who hires Colin recites the rules: “No stage costumes or accessories may be worn other than at the theatre. You will supply your own make-up. … And with every costume a jock strap must be worn.” The chorus members are well differentiated, if a bit stereotypically, with some bitchy, some weepy, all envious of the stars of the show, and all bound by sisterly camaraderie. Josie explains why she joined the chorus: “Let’s face it, when the American ‘invasion’ came—all those big shows from the States, Oklahoma! and Annie [Get Your Gun] and the rest of them—it was no good pretending I could look a hundred percent he-man. Theda Bara, dressed up like a cowboy!”

The other book, dealing with the love triangle, is almost a romance novel in that it gives a picture of gay life, not as it actually was at the time, but as it could be imagined by a gay man in 1959. For example, there’s no institutional homophobia, just a few remarks that are easily rebuffed. Discretion is a must, but there’s no real danger. There’s also no sex. Everyone, including Colin, attests to having “managed to escape the temptation of promiscuity.” As in a Hallmark movie, love is the only thinkable outcome.

Alan is the focus of the romance novel. We get an extensive back story on him: married and divorced early, he had a male lover, a fellow soldier who died in the war. He’s ready for another. There is one requirement, revealed in his description of how men in pubs recognize each other: “[It’s] expressed in the knowing smile of a sailor, the conscious physical pride of a soldier in kilts … in other smiles, too, less endearing—from the bitter old ‘queens’ who watched and waited.”

A pattern that I’ve noticed in many of the early gay novels is the need of the protagonists to define themselves against effeminate men: the soldiers and sailors against the queens. There’s often a scene involving flaming queens from whom the protagonist and his intended can withdraw. We’re not like them, they reassure themselves, and we’re not interested in other men like that. In this novel, the Merrie Belles perform this function. Both Alan and Jock tell Colin repeatedly that he’s not like the queens in the show. And he’s not—he isn’t merged into a drag identity the way the others are—but their insistence reveals a certain crisis of masculinity. They’re horrified that their beloved might be like those others. In the end, masculinity is rewarded with love, the queens are off to look for another show, and Colin has made his choice between the two worlds.

What intrigues me is that the two parts of the book are at war with each other. The romance half rejects the queeniness that’s the entire point of the theater half, which is also the more interesting part of the book and in fact the main reason for reading it sixty years later. The tension between the halves re-enacts a basic split in the gay male psyche, where masculinity polices effeminacy, which nevertheless keeps slipping off the leash. This tension, to my mind, is not resolved or even acknowledged.

I doubt that Buckland, whoever he was, intended this paradox. He probably had some experience with a drag show and wanted to write about it, and to provide structure he added a romance plot that, like all romances, expresses a wish fulfillment. The result, with all its self-contradiction, is still worth reading, and I’m glad that Valancourt has seen fit to make Chorus of Witches available again.

Michael Schwartz is an associate editor of this magazine.