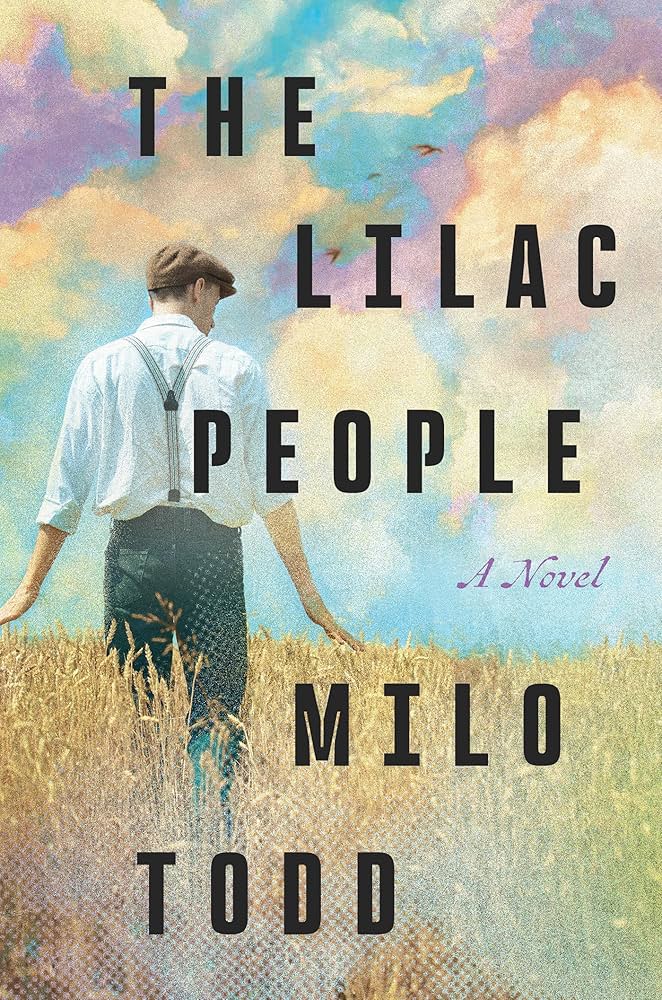

THE LILAC PEOPLE: A Novel

THE LILAC PEOPLE: A Novel

by Milo Todd

Counterpoint Press. 393 pages, $27.

DURING the liberal atmosphere of Germany’s Weimar Republic (1918–1933), Magnus Hirschfeld—physician, sexologist, and activist—established the Institut für Sexualwissenschaft (Institute for Sexual Research), which opened in Berlin on July 6, 1919. Hirschfeld and others at the Institute researched all aspects of human sexuality without moral judgment. A short-term goal was the repeal of Paragraph 175 from the German penal code, which was the statute that criminalized male homosexuality. The Institute also housed Hirschfeld’s museum of sex and a vast library of photographs and written material on sexual matters. It also offered rooms for people who stayed at the Institute as researchers or research subjects. (Among the guests were Christopher Isherwood, W. H. Auden, and André Gide.) The Institute was a valuable haven for transgender men and women who found support, medical care, surgery, and employment.

It all crashed and burned, literally, on May 6, 1933, when Hitler’s stormtroopers entered and looted the Institute and burned its books, photos, and files. The liberal Weimar Republic gave way to the Third Reich, as gay people were rounded up and taken to the detention camps along with Jews, gypsies, the disabled, and others marginal social groups.

When the Allies defeated Germany and liberated the camps, the surviving detainees were returned to some semblance of normal life—except for the LGBT folks. Instead, the Allies continued to enforce Germany’s Paragraph 175 and sent those folks to prison to serve their full term. From the camps to military prisons, from imprisonment by the Nazis to imprisonment by the Americans and British, was not liberation for LGBT Germans in any sense of the word. The American military hunted down gay and trans people every bit as viciously as the Nazis had done.

Milo Todd’s The Lilac People is set in those two moments in German history: in 1932–33, before and while the Nazis were seizing power, and in 1945, when the Allies arrived. Bertie, a middle-aged trans man, and Sophie, his middle-aged cisgender girlfriend who met at the Hirschfeld Institute, have been hiding in plain sight in a kind of marriage. Bertie had been one of Hirschfeld’s employees at the Institute; he was there when the Nazis looted the Institute and burned its contents, barely escaping capture during the raid. He and Sophie went on the run to escape persecution. After years on a secluded farm, hiding first from the Nazis and then from the Americans, Bertie, Sophie, and another trans man named Karl make their way to Amsterdam and onto a ship sailing for New York City. The trip is long and dangerous, but they manage to survive it. Once ashore, Karl asks: “So… what do we do now?” Sophie responds: “Live.”

In its presentation of the jarring contrast between life for LGBT people right before the Nazis took power and right after they lost it, The Lilac People is highly effective. In the sections dated 1932, a time of tolerance for “others” in Germany, Todd gives us a close, entertaining glimpse of queer life in Berlin. The El Dorado, a gay bar, gave refuge and carefree entertainment to a community hungry for it after the deprivations of WW1. The Hirschfeld Institute provided guidance, employment, and emotional and physical care to the city’s gays and lesbians. Although the anti-gay Paragraph 175 was still on the law books, it was seldom enforced, and gay men simply ignored it. Despite the worldwide financial crash of 1929, LGBT folks fashioned a genuine, thriving community—the lilac people.

But then the Nazis came to power, and Paragraph 175 was vigorously enforced—even though Ernst Rohm, the head of the Nazi paramilitary group that enforced the ordinance, was himself a gay man. Gay men (and those suspected of being gay) were rounded up, tortured, sent to the work camps, and eventually murdered in the death camps. Those who managed to evade capture lived under constant, maddening fear of being caught. Gay bars, theaters, cafés, and other meeting places were raided and sometimes razed to the ground. And of course there were the tens of thousands of gay men who were murdered in the death camps (though nothing approaching the millions of Jews). Even Rohm was eventually executed.

The Lilac People is a moving, carefully crafted novel with memorable characters trapped in the most inhumane circumstances. The three main characters must muster hope and determination to fight their fear of entrapment and death simply because of who they are. Todd has created a simple story of human suffering and escape that occurs in the midst of world-shattering events. It may seem odd to some readers that the Nazis and the Americans are presented as almost equally villainous in their treatment of gay and transgender people. For some, it will be quite a revelation. If so, it is an overdue acknowledgment of reality.

Hank Trout, a frequent contributor to these pages, is the former editor of A&U: America’s AIDS Magazine.