WE TEND TO FORGET that Andy Warhol was a writer, sort of. During his lifetime, he published several books, notably a: A Novel (1968), The Philosophy of Andy Warhol (From A to B & Back Again) (1975), and, posthumously, The Andy Warhol Diaries (1989). The Diaries’ 807 pages were edited by his assistant Pat Hackett, who had taken down the text as Warhol dictated it by phone every morning beginning at 9:00. The daily account begins in November 1976 and concludes in February 1987, only a week before his death. Hackett had collaborated with Warhol on an earlier book, Popism: The Warhol Sixties (1980), a retrospective tour of the Pop Art movement, which propelled Warhol into his greater fame. Hackett had a better grasp of grammar and spelling, which was largely ignored in the earlier books, and she was a more accurate typist than Warhol. In her introduction to the diaries, she says she did little editing, with the aim of keeping intact Warhol’s speech patterns and tone, his “voice.”

That’s a convenient segue to the biopic series The Andy Warhol Diaries, directed by documentary filmmaker Andrew Rossi for Netflix. The series is a montage of video clips shot at key moments in Warhol’s life, with voiceover text drawn directly from the diaries. The monologue is done in Warhol’s voice or, more accurately, an “impression” (in the comedian’s sense) of it. Actor Bill Irwin read the text, which AI then remastered to sound like Warhol’s voice. This is the perfect touch for an artist much of whose work deals with copies, what French cultural theorist Baudrillard terms “simulacra.” In an interview conducted for a retrospective of his work mounted in Stockholm in 1968, Warhol said: “Machines have less [sic]problems. I’d like to be a machine, wouldn’t you?” He also said: “I do have feelings, but I wish I didn’t.” A robot replicating and standing in for him would be the fulfillment of that wish. Rossi’s film covers the awkward moment in 1981 when Warhol actually did have his face copied in latex so that it could be placed on a talking robot. The idea was to feature the replica in a stage work titled Andy Warhol: A No Man Show, designed to tour globally while “the real Andy” stayed home. Performances would include a Q&A segment during which the simulacrum would answer questions from a captive audience. The fact that the show never really got off the ground hardly matters. In an art scene dominated by Conceptualism, all that’s finally required is a description of the project, not its material production. That said, with the advent of AI avatars, it will now be possible for Warhol’s project to be realized onscreen.

It’s easy to understand why Warhol wanted to escape his feelings, born as he was into difficult circumstances.

His mother Julia Warhola was an immigrant from Ruthenia, an East European province without any markedly individual character, tossed around like a football among several larger powers over the centuries. (The region is currently part of Ukraine.) Julia married, immigrated, and settled down with her husband in a dismally poor section of Pittsburgh. Here she brought up three sons, her resolute devotion on one hand familial, and on the other, religious. She attended the local church, which practiced a form of Catholicism heavily influenced by the Eastern Orthodox rite. Andy, the youngest and favorite son, attended services with her. In fact, he never entirely abandoned churchgoing, somehow managing to square it with life as a gay man—a gay man associated with worldly success in a decadent mode. Not far along in Andy’s childhood, his father died, a dire setback to a family already scraping by below the poverty line. Andy learned to count every penny, an obsession he clung to long after becoming a multimillionaire. One symptom of that obsession in his diary is his tic of recording the fare of absolutely every taxi he took, dollar figures interrupting—with comic effect—the cavalcade of glittering openings and parties.

Of the diary Hackett has said: “But whatever its broader objective, its narrow one, to satisfy tax auditors, was always on Warhol’s mind.” It seems the IRS began auditing Warhol’s return every year after he provided a poster for the McGovern campaign. Meanwhile, whenever his poorly paid Superstars hit him up for extra cash, he made them sign a receipt saying that the sum was payment for services promoting Warhol Enterprises and thus a business expense. Warhol’s manic efforts to amass and preserve capital ultimately evolved into an æsthetic theory: Business was Art, he said—in fact, the greatest art of all. Maybe it was, but financial success also calmed fears of being thrust back into the penury of his early life.

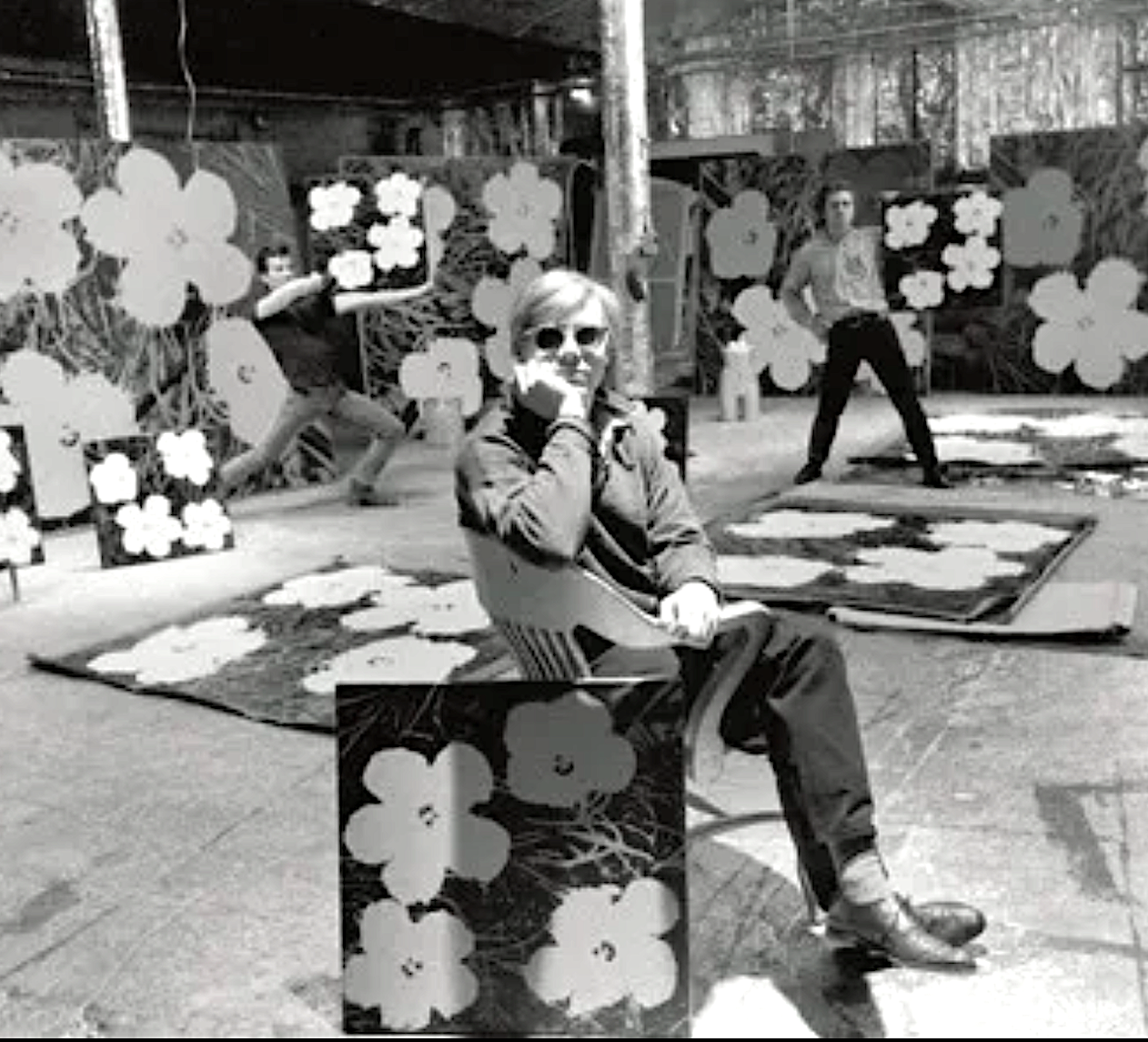

From Factory Andy Warhol Stephen Shore.

Andy was a sickly child, sometimes housebound for months. He would then be nursed by his mother, who often served him soup, though they were too poor to afford Campbell’s. She would heat water, add ketchup and pepper to it and—bon appétit! When he was well enough to go to school, he was ignored or else bullied as a sissy or mocked for the blotched complexion his illnesses had caused. A better alternative was sick leave at home, where he’d be coddled by Mom. To forestall boredom, he began making drawings and watercolors, showing unusual talent for a boy his age. One of his drawings won a prize judged by the German Expressionist George Grosz, though its deliberately grotesque imagery was repellent to everyone else. During those early years, Andy also fell under the spell of Hollywood and its iconic stars. One way to understand his mature work is to see it as an effort to make trashiness kind of glamorous, and glamour kind of trashy. The first category of subjects is raised up, and the second pulled down, so that everything ends up on the same plane.

As for personal psychology, in his teens Andy realized that he was attracted to boys, a predisposition most people regarded as a private disaster in the years before Gay Liberation. The best available remedy was to go to the metropolis. So, after getting his degree in graphic design, Warhol set out for New York. The apprentice’s lean years soon gave way to a successful career in design, a decade of doing stylish graphics for fashion houses and dressing windows for department stores. No doubt he had, even during the repressed 1950s, brief sexual encounters and longer affairs, but little information about them has surfaced. Warhol never spoke publicly about sex, staying resolutely in the closet even as it slowly went transparent around him. He didn’t have to come out; everybody knew. When asked, he claimed to be uninterested in sex, since it brought with it emotional stresses that he didn’t care to endure. The closest he comes to forthrightness is in the Philosophy book’s chapter titled “Love (Senility),” in which he says that sex as an adult is really a nostalgic effort to recapture the first encounters experienced in youth. In other words, sex is nostalgia for sex.

The diary gives no facts about love affairs, but the TV series establishes that he did have two long-term relationships at the height of his fame—first, with an office assistant named Jed Johnson, and later with the Paramount executive Jon Gould. It seems, though, that this second relationship was one-sided, with Warhol showering presents and money on Gould, who was only occasionally available to spend time with Warhol. Physical details about Warhol’s relationships don’t seem to have been recorded. Warhol and his two partners, now dead, never spoke publicly about what went down.

§

Everything there is to know about Warhol has already been discovered, or nearly so. We can now see reproductions of his early commercial work: highly stylized pictures of shoes and other fashion accessories, rendered with pinprick pointiness and a faux-Edwardian whimsy that recalls drawings The New Yorker often published in that era. It was in that magazine that Warhol discovered Truman Capote, the only writer that he seems to have cared much about. He courted Capote (by mail) with notes and little booklets of his drawings, hoping they would capture the writer’s interest. But, no, he was brushed aside along with so many other starry-eyed wannabes. Another influence on Warhol at that time was the fanciful nostalgia on show at the uptown dessert place Serendipity 3, a favorite haunt of gay New Yorkers in the 1950s. Serendipity pioneered the revival of Tiffany lampshades and devised a jaunty, chichi ambiance well suited for the drawings that management allowed Warhol to display on its walls. Meanwhile, his butterflies, high heels, and winged cupids found a ready reception in fashion magazines and often won industry awards.

Despite his success as a commercial graphic artist, Warhol wasn’t satisfied. Ambitious young rebels like Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg, who were just beginning to emerge around 1960, thought what he did wasn’t real art, just swish commercial stuff. The new generation had become dissatisfied with the dominant orthodoxy of Abstract Expressionism and its transcendental ambitions, a program cut off from contemporary America and from our brand of ironic humor. Johns’ flags and targets and Rauschenberg’s assemblages were a frontal assault on the tenets of the older movement and its methods. Since Warhol didn’t do abstraction, he must have seen these new initiatives as a step in his direction. In 1961, he assembled a window treatment for Bonwit Teller that incorporated some graphics drawn from comic strips—Popeye, Olive Oyl, and company. Soon thereafter, Roy Lichtenstein produced his first comic-strip paintings, but he claimed he hadn’t seen Warhol’s window. Maybe Pop sensibility was just filtering into the atmosphere of the day.

Early in 1962, Warhol asked a friend named Muriel Latow what he should do. She replied: “Paint something you love.” He asked what that might be and was told: “Money.” So he began painting a two-dimensional grid of dollar bills, each slightly different from the last. She also said: “Paint some familiar object that’s so ordinary nobody pays attention to it.” That’s when he settled on the Campbell’s soup cans theme, a step up from his mother’s ketchup substitute. From there he went to Coca-Cola bottles and Brillo boxes. Warhol had probably seen Johns’ sculptures titled Painted Bronze. These were bronze casts, first, of a Savarin coffee can and then of Ballantine ale cans, which were shown at the beginning of the ’60s. Why not go there? Pop, bang, shazam went a new art movement, the most influential of the decade—so much so that elements of it are still with us today.

Warhol’s decision to call his East 47th Street studio “the Factory” was designed to link the making of art to capitalist industry. An æsthetic of machine replication aligns well with Walter Benjamin’s 1935 essay “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” though it’s not certain whether Warhol ever read it. Meanwhile, his decision to cover the Factory’s walls with reflective tinfoil hints at his program. Art may offer a higher, purer alternative to barebones reality, but just as often it aims to mirror the world as it really is. Warhol decided that his project was to reflect who and what we are, even if the resulting picture was unexalted—commercial, money-grubbing, shallow, consumerist, hedonistic, and so on.

But mirroring in Warhol’s case was complicated by his sexual orientation and, paradoxically, his religion. One way to think of his œuvre is as the outsider’s revenge. The world that excluded a plain-featured gay youth who liked attending church is portrayed as amoral and vapid. There might be attractive and even profound aspects to 20th-century experience, but those weren’t going to be his subjects. Catholic theology sees us poor creatures as fundamentally flawed, irredeemable in the absence of faith. That aspect of human nature was to be Warhol’s focus, not the nice side. Nor was Warhol going to restrict himself to paint and canvas. The Hollywood fan would break into filmmaking, even if his only tool was a 16mm camera. Underground auteurs like Maya Deren and Jack Smith had opened the field, and the price of admission wasn’t prohibitive. Warhol’s early efforts were more in the category of Conceptual Art than cinema. Sleep (1962) is simply the record of his boyfriend John Giorno’s slumber throughout one night, as filmed by a stationary camera. In Empire (1964), the same fixed camera focuses for eight uninterrupted hours on the Empire State Building, as background skies change, sunset arrives, and lights come on. Warhol planned to go further in later, more animated efforts. But the documentary obsession remained with him to the end. He brought a Polaroid camera to social events and later a portable Sony tape recorder, which he referred to as “my wife.” Image and soundtrack were preserved for their intrinsic value as factual, ephemeral moments whose mindlessness or humor or vanity would be captured for later inspection.

Toward the end of 1964, a young unknown writer came to take one of Warhol’s “screen tests,” which consisted of three minutes of silent gazing at the camera—more an act of portraiture than an actual audition. The young writer was Jewish, coolly attractive, and the author of an essay titled “Notes on Camp,” published a few months earlier in Partisan Review. This was Susan Sontag, who never appeared in a Warhol film. Nor does it seem she cared about his work. After all, her essay on camp was a brief departure from much more challenging discussions of politics and culture. But for Warhol, camp sensibility is central, the mode he adopts in the mirror being held up to America. A mode of satire pioneered by gay men, camp goes beyond any parochial subculture. Camp humor is directed at things with extravagant ambitions that embarrassingly don’t succeed, as well as objects or people that are mindless or insipid to the point of absurdity. Camp sensibility is often trained on cultural phenomena that have now passed their sell-by date and hence appear overdone, vain, grandiose. Old Hollywood is fertile ground for camp, as the movie Sunset Boulevard acutely establishes in scenes like the one in which the character Norma Desmond retorts: “I am big. It’s the pictures that got small.” Camp is also directed at the “pure products of America,” the middle-class banality of supermarket brands, their cutesy ad slogans and depressingly cheery graphic design. Hence Warhol’s soup cans and Brillo boxes. He saw that “At GE, progress is our most important product” and “It’s not fake anything. It’s real Dynel.”

Camp satire isn’t relentlessly supercilious, though. What it does is make failed ambition or naïveté a source of pleasure. Warhol said that Pop Art was about liking things, things that are so bad they’re good, even if “good” in a way the creator or performer hadn’t intended. One can cite, for example, the singing career of socialite Florence Foster Jenkins, whose gravely inadequate vocal skills made her a camp success in New York. Giggles and howls from the audience were always louder than any wobbly note she produced. Without camp, her career would have been a catastrophe. And yet, gazing for long through the camp lens is risky because its photoshop effect begins to expand, ironizing and emptying out everything it overtakes. In the end, everything is camp and nothing is sacred—above all, sacred things.

Of course, camp perspective can go only so far. In the 1970s, Warhol heard a rock performance he described as “so bad it’s not good.” Compare that with a remark Gore Vidal made after seeing the New York Dolls: “Just being bad isn’t enough.” Some forms of failure can’t be rescued by a camp focus. We can wonder whether Warhol’s own self-transformation from blasé sophisticate to bewigged, camp faux-naïf was fully successful. Pop strategy dumbed him down into a bubblegum American teen with a vocabulary seldom ranging beyond drawled effusions like “Gee,” “oh wow,” “that’s gre-e-e-at,” and “oh, uh, I don’t know,” or “yeah, that’s really up there.” His faked simplemindedness was an astute mirroring of American blah and made him less intimidating to the audience than “serious” artists. On the other hand, it also devalued him in the minds of observers who didn’t look beyond the mask.

It’s not surprising that camp has flourished more in the U.S. than elsewhere. Americans with education and travel experience develop a stereoscopic perspective on our culture, which sometimes proves to be astonishingly empty. For the most part, the depth and complexity of the European or Asian counterpart is replaced by one-dimensional sentiment or else taboo-flaunting and carnivalesque fun. Most of what’s churned out for the mass market is made for a society in which education is spotty and “there’s a sucker born every minute.” Even so, we’re fond of our cultural products; they’re relaxed and comfortable and, like Nabokov’s Lolita, kind of sweet in a sly, candid way. And they are often very funny, if only by the intervention of a camp perspective. Frank O’Hara (in the poem “Naphtha”) says: “I am ashamed of my century/ for being so entertaining/ but I have to smile.” As an art critic, O’Hara was loyal to his Abstract Expressionist pals, who despised Pop Art and expected him to echo their disapproval. In fact, many of his best poems embody a Pop sensibility, such as “Poem: Lana Turner Has Collapsed!”

Uncouth forms of entertainment—cockfights, cat lynching, burlesque, and mudwrestling, for example—have been part of the American reality for at least two centuries. Consider the sideshows (or “freak shows”) that were a regular feature of touring circuses and the Coney Island boardwalk in New York. These shows, a failure in the good-taste department, were the prompt that led to Tod Browning’s 1932 movie Freaks, whose cast included performers with variant body parts. In response to humanitarian criticism, freak shows gradually faded in the early 1960s—no more “Turtle Girl” or Sword Swallower. Susan Sontag later cited Browning’s movie in her critical response to the photographs of Diane Arbus, whose work has sometimes been praised for its humane empathy and sometimes condemned as voyeuristic. It is arguably both, and the same can be said of Warhol’s use of his eccentric entourage. It’s hardly a coincidence that, as public acceptance of sideshows waned, Warhol’s Factory became, beginning in 1963, the haunt of various misfits, coke heads, maverick heiresses, and drag queens, who sprawled about in the tinfoil ambiance, smoking, drugging, shagging, and making bland, demented, or wry remarks. Warhol observed it all and took mental notes, but never much participated. To mirror was enough. In the decade when “freak out” became an expressive bit of slang and counterculture types often referred to themselves as “freaks,” the Factory was there to embody it all.

§

Warhol’s 1950s self-presentation, suitable for Serendipity and the milieu of fashion magazines, had been primly fey. His bow ties, tweed, and Mr. Magoo eyeglasses were just offbeat enough to make an arty but not a bohemian impression. All that was discarded in the following decade when he was reborn as Cool Hand Andy, someone hipsters like Lou Reed and Mick Jagger wanted to hang with. But it’s clear that the “freaks” who interested him most were the drag queens: camp figures most of whom were too exaggerated to pass as women. The credible exceptions were Candy Darling and Potassa De Lafayette. Drag queens were extravagant simulacra of women that camp sensibility could revamp as successes in the mode of comedy.

As for the argument that labeling them as camp is patronizing, consider the fact that their stage names were deliberately adopted for their parodic value. Those names could be witty, as in the case of Holly Woodlawn, which evokes Hollywood as well as Woodlawn Cemetery in the Bronx. The Factory itself was a sort of graveyard of delusional dreams, given that its denizens (except for Candy Darling, Viva, and Joe Dallessandro) never managed to achieve much outside its precincts. Warhol took his cue from Ingrid Von Schefflin, who early on renamed himself Ingrid Superstar and began using it as a generic term for others in his faithful flock. Far from certifying actual stardom, the prefix “super” only confirmed that the category was an amusing simulacrum of the real deal. His superstars acquired something like fame by association with Warhol, but finally were famous only for being famous. Meanwhile, cis women who became superstars, like Brigid Polk, Viva, and Ultraviolet, worked hard to appropriate the showboat extravagance of the drag queens—simulacra of simulacra, and as such a rich field for Warhol to explore. In a clip from one of the early documentaries about Warhol, Viva is fawning over him, saying how good he is, and that he “sees God in everything and in everybody.” She concludes: “They call that art.” The camera zooms in on the artist himself, wearing his very hip sunglasses as he murmurs “Fudge.”

The famous Warhol films that his superstars appeared in (Chelsea Girls, Women in Revolt, Flesh, and Trash) were directed not by Warhol but by Paul Morrisey, to whom ideas and financing were given by the remote-control auteur. These films were quasi-fictional and quasi-documentary, allowing the superstars to improvise around thin, intentionally pixilated plotlines. Warhol seems to have imagined that his films would persuade the regular movie studios to welcome him into the industry, but no exec was ever beguiled enough to invite him to Tinseltown. “Underground” as they were, the Morrissey films made money, and by the 1970s Warhol was a multimillionaire, his bundle based on the sale of paintings, prints, portraits commissioned by the superrich, and finally the movies.

Where fame and money abound, people of every description flock, creeping out of the woodwork to get a piece of you. Enter Valerie Solanas, the most freakish of them all, who went so far as to gun Warhol down (her version of a film shoot) when he declined to produce a play she’d written. After the fact, she was asked if she felt any remorse. She said she did—for not having practiced enough to aim higher. That bonkers answer helped qualify her for a long stay in a mental institution, which preempted criminal prosecution. Meanwhile, Warhol nearly died on the operating table and emerged from the experience with a closed-mouth version of PTSD, whereupon the Factory’s notorious permeability came to an end. A stern front desk was set up and security features installed. The focus shifted from freaks to business, with a coat-and-tie dresscode for male staff members. Operating as Andy Warhol Enterprises, it now incurred hefty overhead costs, notably salaries for the team, whose members complained of low pay and long working hours. To bring in income, Warhol constantly drummed up lucrative portrait commissions, directing his employees to help him woo potential customers. Warhol had proclaimed Business as Art but may not have anticipated that running a successful business may involve time-consuming tasks, boredom, and burnout.

In the 1970s, nightlife became a key pastime for Warhol, partly because the Factory had become too unfreaky to be fun and partly because gossip-column coverage raised his profile. Besides, rubbing shoulders with oligarchs who liked fashionable nightlife led to further portrait commissions. It dawned on him that clubbing, too, was Art, one that counterintuitively boosted its sister occupation, Business. Surveying Warhol’s activities as reported in the’70s diary calls to mind the Whatever-Happened-To and Where-Are-They-Now parlor games. Survivors from that era will smile at the mention of Le Jardin, Bianca Jagger, Taylor Mead, Régine, Egon von Fürstenberg, Sylvia Miles, Lance Loud, Fiorucci, Tama Janowitz, the Cockettes, Jerry Hall, Elaine’s, Nan Kempner, Nell’s, Peter Beard, and Steve Rubell. Studio 54 founder Rubell has since died, but the 54 survives in the history of New York City nightlife. It opened in April 1977 to an enthusiastic swarm of scene-makers, a crowd that included Ivana and Donald, always eager to boost the Trump brand.

Within weeks, the 54 had become a hangout favored not only by Warhol and the Factory but by the entire Halston retinue, its most prominent members being Liza Minelli, Elsa Peretti, and Venezuelan-born artist Victor Hugo. The latter devolved into a sort of shuttlecock between Halston, who discovered him, and Warhol, who found him intriguing and fun. Hugo had moved up in Manhattan gay circles, propelled by wild ambition and a zeal to be zany, all of it supported by good looks and other physical endowments. Under Hugo’s influence, Warhol produced his “Landscapes” series, which began as Polaroids of sex acts performed by hustlers Hugo brought to the Factory, producing images that were then transferred to silkscreen. Factory assistants disliked Hugo and disapproved of a visual series they considered pornographic, but Warhol had seen what Robert Mapplethorpe was up to and wanted a piece of the action, which in any case he found titillating. Unfortunately, this sudden new interest in “landscapes” alienated his handsome partner Jed Johnson, whose objections went unheard. Without much warning, Jed left Warhol’s East 66th Street townhouse and settled down with someone else. Warhol pretended not to be surprised or to mind, but close friends could see it was one of those occasions when he’d have preferred to be a robot with no feelings.

The ironic mirroring of American celebrity culture took the form of serigraph portraits of Elvis, Marilyn, Jackie O., and Liz, and it led to the launch of his tabloid-format magazine Interview, Warhol’s answer to People. At first it was a money pit, with sales and advertising never fully offsetting overhead. But by the 1980s, it began to take off. The quest for interviewees for the magazine cover was parallel to Warhol’s constant trawling for new portrait commissions. He seems to have set the fame bar rather low, granting celeb status to anyone in the movie or TV business, anyone socially prominent in New York, anyone in the fashion industry with name recognition, rock stars, visual artists in vogue, higher-ups in government, and of course Superstars famous for being famous. In one of his diary entries, his description of a party he attended is summed up in the comment: “Everybody was somebody.” It’s a perspective that lines up well with his best-known pronouncement: “In the future, everyone will be world famous for 15 minutes.”

§

Unlike Truman Capote, Warhol was never fully incorporated into New York’s upper crust, never, for example, on intimate terms with the likes of the Wrightsmans or the Paleys. But he was content to operate at its periphery. It’s a milieu that enjoys having a gay court jester, and Capote was brilliant at being one until the publication of Answered Prayers. The mordant satire of his socialite friends in the book foreclosed on his privileged position among them. He was still a star in Warhol’s eyes, though, and a request for a regular Capote column in Interview was accepted. After all, Capote’s reputation had by then come down several pegs, whereas Warhol had become world famous. Most of the pieces in Capote’s Music for Chameleons were first published in Interview, and he was given the cover for one of the issues.

Because of his international reach and his association with multimillionaires, Warhol’s portraits eventually moved beyond showbiz subjects and Chairman Mao, landing commissions from heads of state or at least their wives, among them Jimmy and Rosalynn Carter. Word spread. In those years Fereydoon Hoyveda, the Iranian ambassador to the UN for the Pahlavi regime, was a notable figure in New York’s café society and several times gave parties for Warhol and his friends at the Iranian consulate. Champagne flowed and golden caviar was scooped up by guests who somehow managed not to be aware of the Shah’s human rights violations, his prisons, and torture squads. Friendship with the ambassador resulted in an invitation to Iran’s Festival of the Avant-Garde and eventually a portrait commission from the Empress Farah Pahlavi. The portrait series was completed but never paid for because, with little warning, the Iranian Revolution erupted, upending the Peacock Throne and sending the Shah into exile.

Other clouds were gathering. In 1979, Studio 54 was raided and shut down on drug charges. Steve Rubell took a plea deal for tax evasion but still had to do time. On his release, he opened the Palladium on 14th Street, which Warhol also frequented, though it never achieved 54’s iconic status. With the early 1980s came the AIDS epidemic, taking the life of Jon Gould, Halston, and eventually Rubell. Candy Darling died of cancer, other Superstars drifted away, and Warhol’s health declined. A brief artistic springtime blossomed when Jean-Michel Basquiat signed on at the Factory, leading to a double-header show that featured collaborative works made by the two artists. The initial critical response to Basquiat was negative, with one reviewer calling him Warhol’s “mascot.” Wounded, Basquiat withdrew from the friendship, more and more sinking into drug addiction, which led to the inevitable overdose. That came a little over a year after Warhol’s own death in 1987, a death that apparently resulted from poor hospital care. After many years of pain and discomfort, Warhol had finally agreed to a gallbladder operation, which was deemed successful by the doctors. But during the following night, his lungs filled with IV fluid and he suffocated.

Warhol survives and thrives in his afterlife. Audiences can respond to his art without invoking theory or in-depth analysis. His artistic repertory recycles familiar products and faces from popular culture. That includes Warhol himself, who became a recognizable icon long before his death, his clownish fright wig an instantly recognizable feature. For those reasons, his work has been much more popular with the broad public than is common for avant-garde art, a popularity that put him in a bad light with his more serious-minded contemporaries.

Warhol himself didn’t have a high opinion of his gifts if we take his word for it. At a party celebrating Leo Castelli’s twenty years as an art dealer (in March 1977), Warhol told his diary that he was uncomfortable and bored, describing the occasion and guests as “just the kind of party I hate because they are all like me, so similar and so peculiar, but they’re being so artistic, and I’m being so commercial that I feel funny. I guess if I thought I were really good, I wouldn’t feel funny seeing them all.” During a meeting with an ad agency that planned to use him in an endorsement, someone asked him how he got to be so “creative.” He answered: “I’m not.” And when, at the opening of one of his shows, an interviewer remarked that critics had said his work was no good, he said: “They’re right.” My guess is that he simultaneously did and didn’t think that was true. Evaluating Warhol is a slippery task because it calls into question standard æsthetic canons. He didn’t want to be grander or purer or more profound than the material and social context surrounding him. Instead, he saw his work as a depiction of what that context was. Parodic mirroring, Warhol style, could lend an artwork social and philosophical significance even when flash and irony stood in for skill and sublimity. We might not feel profound admiration for his work, but we have to smile and sigh: “He nailed it.”

When Warhol said that Business was Art, the remark registers as more than a joke once the field is narrowed to the art business itself. By 1970, Warhol had come to understand (and take advantage of) the symbiotic interaction between cutting edge visual art, the media, price tags, and clients eager to acquire social status by espousing the avant-garde. There was also the gallerists’ and buyers’ profit motive, since anyone who had access to insider tips could get in early with the new hot thing before its price soared. It was in the 1970s that corporations began buying new art after seeing that profits made from reselling it could outperform conventional investments. Warhol grasped that the operation of this interlocking process was a form of Conceptual Art, a high-definition rendering of the interface between contemporary culture and capitalism. The concept does require making actual artifacts, but these must be radical in form and/or content so that the media will want to write about them. Mordant satire; sex, drag, and rock n’ roll; gigantic scale; high-low mashups; horror; freakishness; and cutesy sentiment are all reliable means of getting media coverage—which leads to sales. Eventually, the artists themselves become media icons, namechecked by the in-crowd and courted by collectors, all of which adds to the allure of the artworks just as it boosts prices. Warhol’s transmutation of the art biz into Art itself must have been gratifying not only as an innovative idea but also as a means of “bringing home the bacon,” his preferred euphemism for making money.

If importance in visual art is judged more by impact than by formal achievement, then Warhol must be considered the most important American artist of the second half of the 20th century. We might say “alas,” but that does nothing to change the fact of his influence, which has been overwhelming. The briefest sampling of the work of, say, John Ashbery, Larry Rivers, Alex Katz, David Hockney, Cindy Sherman, Fassbender, Almodóvar, Jeff Koons, Bruce Nauman, Tracey Emin, David Bowie, Lisa Yuskavage, RuPaul, and Lady Gaga makes this point. His influence has in fact ranged far beyond the enclave of art and inscribed itself in our sensibility, governing what we notice and how we respond to it. Consider, for example, reality TV, graffiti art, Barbie, The Simpsons, Hairspray, advertising, video games, “deep-fake” avatars, and TikTok. Since the 1980s, hip folk have aspired to the condition of Warhol, perhaps only for 15-minute screen tests or karaoke sessions returned to from time to time during the onrush of our Disneyworld decades.