ALGER HISS was on a very clear trajectory toward becoming our nation’s Secretary of State—after helping to found the United Nations—when, in 1948, he was repeatedly and publicly attacked, for reasons I now see as politically motivated, clearly false, possibly pathological, and definitely homophobic.

Alger Hiss was also my stepfather. At age 91, I am the last living eyewitness to this dark moment in our country’s history, commonly known as “the Alger Hiss Case.” I’d like finally to close this chapter in our history—to the extent possible in this age of fake news and falsified history.

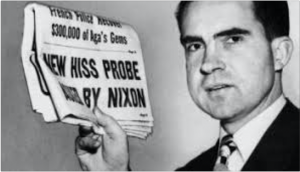

The attacks on Alger Hiss came from none other than the future president Richard Nixon, who was hoping to win his first term in the U.S. Senate. Also attacking Hiss was the notorious Senator Joseph McCarthy, whose purge of suspected Communists was in full swing, and his lawyer Roy Cohn, a closeted gay man. Among Cohn’s many high-profile clients later in his career was Donald Trump, a relationship that lasted for many years until Cohn’s death from AIDS in 1986.

Finally, lurking throughout the Hiss Case, and especially as it concerns my role in it, was J. Edgar Hoover, director of the FBI for almost fifty years—and another closeted gay man. He maintained his power—and his secret—through a huge, private collection of dossiers on the personal lives of every politician or power broker who mattered in Washington, including presidents. He even had a file on me (about which, more to follow).

Finally, there was a brilliant writer who would later become a contributor at Time magazine (1939-48) named Whittaker Chambers. For reasons that have yet to be fully disclosed, Chambers set out to use his position—along with the paranoid mood of the country at this time—to ruin the reputation of Alger Hiss and end his career. There are some questions that must be raised, and which I will try to shed some light on here: To what extent was Chambers motivated not by civic duty but by a personal grudge against Hiss? Was Chambers gay? If so, how might this fact explain his desire to destroy Alger Hiss, whom he had encountered years earlier, when both were young men?

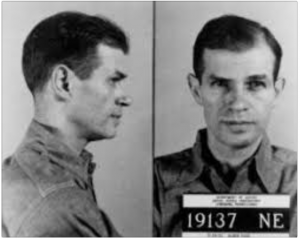

With the full support of Nixon and Hoover, Chambers first accused Hiss of being a Communist under oath before a House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) hearing on August 3, 1948. Chambers, himself a former member of the U.S. Communist Party, testified that Hiss had secretly been a Communist while in federal service. In response, Hiss asked to testify before HUAC, where he categorically denied the charge. When Chambers repeated his claim on nationwide radio, Hiss filed a defamation lawsuit against him. Under oath, Hiss denied even remembering Chambers, though later he recalled him, not as Chambers, but as a journalist named George Crosley. Chambers, by that time, had ridden to dubious fame as a former Soviet spy. He claimed he was an intimate personal friend of Hiss and his family, and had dined with us on many occasions. After denying these charges under oath, Hiss faced perjury charges, and after two federal trials he was sentenced in 1952 to two concurrent five-year terms in federal prison.

§

Now add me to the story, a young man when my stepfather, Alger Hiss, was enduring these accusations from Whitaker Chambers. But for that story, let me cycle back to the beginning. Born to Priscilla (“Prossy”) and Thayer Hobson in 1926, I was their last-ditch effort to hold the Hobson marriage together. But the marriage failed just one year later, and my mother and father were divorced—illegally, in Mexico. Thayer, luckily for me, had two wonderful older sisters who cared for me whenever my mother wanted the freedom to go out gallivanting, as “Prossy” searched for a new husband.

When I was three, in 1929, she met and married Alger Hiss. He became my legal father, and we three lived together in New York City and then in Washington, D.C., as my father started a long and successful career in various departments under President Roosevelt during the New Deal era. In 1936, he joined the State Department.

The supposed evidence against Hiss were the “Pumpkin Papers,” copies of secret State Department files, allegedly stolen by my father, which ended up hidden in a pumpkin patch (hence their name), and then were “discovered” by Nixon. There was considerable publicity about the dramatic efforts Nixon had undertaken to find them in a pumpkin patch on Chambers’ farm in Maryland, and get them to the government.

However, there was no espionage charge against my father until Chambers found himself facing a slander charge by Hiss. One lie under oath followed another as Chambers wriggled out of the slander suit. But from then on, he was very carefully protected (and coached) by Hoover and the government lawyers, as he was the only witness against Hiss. (Chambers, on the other hand, was never charged with his multiple proven perjury statements under oath, since he cooperated with the government.)

During the early part of these proceedings, Chambers gave a handwritten confession to the FBI stating that he had been a “practicing homosexual” (in the language of the day) right up to the time when he supposedly had a final meeting with my father, at which he tried to convince Hiss to renounce his Soviet support.

As I have studied the history of the case against my father over almost seven decades, I have read and reread (and re-lived) Chambers’ charge, his retraction, and his out-and-out lie about his story many, many times. He used a lot of different names and many deceptions and complications in his life. He claimed to have been a close family friend. Hiss did not know him well—except as journalist “Crosby”—and I personally cannot recall ever meeting or seeing him.

And yet, this man destroyed my father’s career and our family’s life, and it certainly complicated mine. All these years later, the discrepancies continue to come to light. The “Pumpkin Papers” were supposedly given to Chambers by my father, after being typed by Prossy on her old Woodstock upright typewriter. There is still a mystery about that Woodstock typewriter. It was found by the Hiss defense team and given to the FBI. It even appeared onstage as evidence in the trial. The big lie was that the typewriter had a production number indicating that it was manufactured after the date of the original “Pumpkin Papers” that my mother had supposedly typed for Chambers! The typewriter also had forged typeface changes and alterations, revealing an attempt to make it look like earlier Hiss typing samples.

It is now known that the FBI investigated records of the typewriter date’s “inconsistencies,” but this was never shared with the defense. They argued throughout the trial that the typewriter entered into evidence was the original machine. “Forgery by typewriter” is one of several mysteries in the government’s case. Experts on both sides presented testimony at both trials. One thing I can speak for, and say with confidence, is that my mother was a really lousy typist, and I seriously doubt she could ever have typed the alleged documents that Chambers claimed she did—on any typewriter, forged or not! Another point to consider is that the FBI never showed the defense team Chambers’ confession admitting to being a “practicing homosexual” until years after my father left jail—which was completely unethical and illegal. But they wanted a conviction that badly.

One obvious question for me has always been: why would a man like Chambers even begin such a barrage of false accusations, which actually dated back to 1939? My belief is that Chambers had fallen in love with Hiss when they first met in 1936, but that he was rebuffed by Hiss and became pathologically hateful toward him. I’m not a psychologist, but a wonderful book by Meyer Zeligs titled Friendship and Fratricide (1967) chronicles the lives of both Hiss and Chambers from a clinical, psychological viewpoint, and points to a history of prior psychiatric episodes in Chambers’ life that have parallels with the Hiss case. Zeligs theorizes a “Hiss fixation” on the part of Chambers, as revealed by the fact that Chambers had acquired and preserved some of Hiss’ possessions.

From my own life and my own personal observations and discussions, I am certain that Hiss would have rebuffed Chambers. I know for a fact that my father knew absolutely nothing about the subject of homosexuality until 1945, when I received an “undesirable” discharge from the U.S. Navy for my own professed homosexuality. He was so perplexed at the time, that it was only then that he and Prossy began a crash course to educate themselves on the subject, to psychologically support and help me.

§

At the trials, the defense based a major part of its argument on what an outstanding man Hiss was, what upstanding citizen. Pages and pages of testimony, and even affidavits right up to a Supreme Court justice, were entered into evidence at both Hiss trials to support this assertion. Hiss was painted as a sort of Eagle Scout who did impeccable legal work for our government—almost a robot of perfection—a figure so unbelievable to some that the government had only to provide a few examples of imperfect work to knock him off his pedestal.

I entered the scene as the only other potential witness. I claimed not to remember Chambers at all, stating that he was not a family friend, that he never came to dinner, and that for three months, during the exact time of the “typewriter” story, I had been lying in bed with my leg in a cast, upstairs, in a Georgetown house with flimsy walls. I not only knew everyone who came and went—the front door of the house was just below my bedroom—but I could hear everything that went on below my room! I never remember having seen or heard Chambers even once, let alone the repeat visits he claimed he made to our home.

What’s more, I never heard my mother typing anything during that period. I even underwent an hour-and-a-half of questioning under pentothal, the “truth serum” of the day, which was administered by an anesthesiologist in the defense lawyer’s office, and nothing new was discovered to counter my memory. Still, consider the legal psychodrama of the defense’s legal team. Despite the value of my testimony, before allowing me to address the court they had to consider how the presence of an openly gay stepson could ruin Hiss’ “Eagle Scout” image.

At both trials, a wonderful family servant who had worked for us at all three Washington homes during Chambers’ period of putative visits stated under oath that she never remembers seeing Chambers, and that he certainly never came to dinner. I offered to testify on behalf of my stepfather, but Hiss himself made the ultimate decision, saying: “No! I will not allow Timmy to testify even if it means I go to prison. I will not ruin his life, as Chambers is trying to do to mine.” By this point of my life, I was in my final years at NYU taking pre-med requirements. Later, I graduated magna cum laude, but I was refused admission to NYU Medical School, as I had included my Navy “undesirable” discharge in my application. However, I feel that my connection to Alger Hiss was also part of that decision.

In the end, Hoover and his FBI team blackmailed me into not testifying at the two Hiss trials. Hoover sent out a team of agents to investigate me and everyone I had ever known or slept with. Many friends called to warn me that FBI was checking my activities. I can clearly recall the two agents who came to my cold water flat in Greenwich Village. They were not impolite but were very official, informing me of their knowledge of my Navy discharge and unsavory behavior in New York City. And they very clearly informed me that all of this information would be released publicly if I ever decided to testify. I never testified at either trial, feeling blackmailed by the FBI and my own government.

I certainly had troubles of my own, and could never accept Alger as a full father figure, though he tried valiantly and earnestly. Psychiatrists have explained it to me thus: “After all, he took your mother away from you.” But I remember him most warmly, and he was almost as perfect as the defense painted him. I even remember his visiting long after his jail time, and teaching one of my sons how to pour water from a pitcher, trying to teach both of us how to throw a ball, etc. I have never known a finer man. I even visited him with his new girlfriend, after he and my mother separated. (Prossy never granted him a divorce, always thinking he would come back, and my stepfather was not able to remarry until after Prossy’s death in 1984.) I am happy that we did finally become close friends before he passed away in 1996.

§

At the time of the trials, Hiss was the President of the Carnegie Foundation for International Peace. He had been the official Secretariat of the San Francisco International Convention that created the United Nations, and was well on the way to becoming Secretary of State. Please humor an old man and let me indulge in a game of “what if” for a moment.

If Chambers had not falsely accused Alger Hiss; if Nixon, Hoover, McCarthy, and Cohn had not been so willing to sacrifice truth and decency for personal advancement; and if 22 diplomatic experts had not been fired at the State Department (for “suspected homosexuality”), I believe we would have had a good chance of avoiding the Korean War. Hiss possessed such diplomatic skills that perhaps a peaceful resolution could have been found—which in turn could have prevented the fiasco in Vietnam that began a decade later.

This possibility leaves me with regret that I didn’t help Hiss when I could. I still have great disrespect for the FBI of those years, and I’m I am still angry at having been blackmailed by the FBI into not testifying. Meanwhile, it appears likely that some documents relevant to the Hiss Case still have not been released to the public. When some day they are, perhaps the truth about Alger Hiss and his innocence will emerge and be accepted once and for all. Perhaps the citizens of today, knowing my story, will be more vigilant to make sure nothing like this ever happens again.