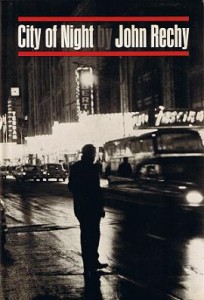

JOHN RECHY’S City of Night was published fifty years ago. The novel is a frank account of the adventures of a male hustler who wanders restlessly around the country in the late 1950s, turning tricks as much for self-affirmation as for money, and scrupulously avoiding any romantic attachment. The book is partly a travelogue, offering a pano-rama of the gay underworld in (chiefly) New York, L.A., and New Orleans, and partly a portrait gallery, with little cameos of clients (“johns”), other hustlers, and drag queens.

City of Night was understood immediately to be path-breaking, opening the way for works like Faggots and Dancer from the Dance in the following decade. But it also had one foot in the past: nearly all the gay men it depicts are bitchy, dejected, lonesome, or hysterical, confirming the stereotype that homosexuals can never be happy. And the narrator doesn’t just describe, but implicitly endorses, the rigid hierarchy of the world he moves in, with queens and pathetic old johns at the bottom, “masculine homosexuals” in the middle, and young, quasi-straight hustlers at the top. So, if the novel is a landmark in gay writing, what it marks is the beginning, not the end, of the transition from the gay “problem novel” of the ’40s and ’50s to the “liberated” fiction of the ’70s and ’80s.

I can say without hesitation that anyone interested in the history of gay writing in America must read City of Night. But I have a harder time deciding whether the book is any damn good.

The year it appeared, 1963, was also the year of the New York newspaper strike that shuttered The New York Times Book Review and led a group of editors and writers to establish The New York Review of Books. The second issue of the new journal featured a blistering review of Rechy’s book, unhappily titled “Fruit Salad,” by the brilliant but deranged Alfred Chester. Chester might be thought of as the Dale Peck of his day, a passionate, slashing critic whose accounts of Albee’s Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf and Nabokov’s Pale Fire are venomous and dead-on. No one who reads Chester can ever feel quite the same about those works again.

Discussion1 Comment

That’s quite a hard grilling of something in essence utterly American by an american. I think you could stand back and relax a little.

The book has certainly earned it’s place . It is in some sense a classic. It’s the precursor of a whole raft of books not to mention films and represents a moment of gay literary shift. The point when the pulp novel, the penny dreadful becomes something else.

There are plenty of badly written works in the stable of gay novels that come after the 70s and the violet quill. Rechy is no less or more a good grafter than many who follow him. What makes this work stand out is the interesting portrayal of NYC 42nd St culture and also some of the depictions of gay life in Hollywood and San Fransico. They genuinely capture an energy and authenticity which one suspects can’t be beaten as a literary point of origin.

I find it a peculiar characteristic of this paper that reviewers are forever to an almost pathological degree drawing literary parallels rather than appraising based on a more coherent form of interrogation. I’m not convinced of the value of mentioning Genet’s name when talking of the City of Night. Genet is in the end something utterly French, his early works capturing a Europe that is all but gone. Rechy, likewise is something utterly American, achieving likewise for that place too. Rechy’s book is far more evocative of the syntax of B movies and film noir than it is of Genet and his own worlds. Is it still a characteristic of american’s that they feel it neccassary to constantly compare themselves to European culture in the process misappraise their own culture whilst appearing terribly self depreciating ?