THIS YEAR I’ve reviewed half a dozen of the ten or so films that I saw in June at the Provincetown International Film Festival—not officially an LGBT film festival, but hey, it’s P’town, so a fair number G&LR-worthy films were on hand.

Here we are fifty years after Stonewall, attending Pride parades and events that are bigger than ever. But does the concept of “Pride” still have the resonance and power that it once did? This documentary sets out to address this question, and—spoiler alert—it answers in the affirmative. State of Pride, which appears to be targeting a younger audience, follows the tried-and-true method of spotlighting one person in each of three cities to guide us through Pride-related events while also focusing on their life story, each characterized by great challenges and triumphs over adversity. In Tuscaloosa, Alabama, a lesbian couple that has endured all the challenges of living in the deep South celebrates the newly established Pride march in their city. In San Francisco, a transgender person finds challenges in belonging to a minority within a minority even in one of America’s most tolerant places. In Salt Lake City, a young gay man who’s confined to a wheelchair due to a spinal injury is forced to choose between “Pride” and his Mormon upbringing, as embodied by his otherwise loving family. For those who’ve been going to these parades for decades, these declarations of “Pride” can seem a little hokey, but their sincerity is not to be gainsaid, and the film reminds us that the adoption of this word—the opposite of shame, homophobia weaponized—was a true stroke of genius.

Vita Sackville-West is known today primarily as the inspiration for Virginia Woolf’s Orlando: A Biography, though she was a popular novelist in her own right—and what a force of nature she must have been to have so inspired one of the century’s greatest novelists. The challenge for director Chanya Button is to create a Vita who’s sufficiently dazzling and multifaceted to explain Woolf’s obsession with this woman, and in this she largely succeeds. It is Vita who seduces a reluctant Virginia in the film (based on a play by Eileen Atkins), first as friend and confidant and then as her lover. But Vita’s habit of seduction, her omnivorous approach to love and life, ensures that she will prove an inconstant paramour. Virginia’s heart is broken, and she decides in a flash to write Orlando about a character who embodies what she sees as Vita’s omnisexual, gender-free, even trans-historical personality. The fictional Orlando is born a man in the 16th century but spontaneously transforms into a woman and lives for centuries in England and abroad, a Zelig figure who pops up in the courts of Elizabeth I and Charles II and befriends the great English poets, notably Alexander Pope.

That Virginia could project Vita onto all of these roles, among others, attests to a remarkably versatile personality indeed. In contrast, in the film Virginia herself comes off as surprisingly conventional and dependent, leaning on her husband Leonard Woolf and those around her to keep her sane (barely). We get only a few glimmers of her genius as a writer; what stands out are the gorgeous period outfits worn by both women and their husbands, not to mention the glittering table settings, sitting rooms, and gardens in this highly style-conscious film. That said, director Button is to be commended for depicting this aspect of Woolf’s life in a forthright way: a passionate affair that was documented in letters written between the two women, the very writing of which was a bold act of feminist independence.

Flouting the current fashion in documentaries, Making Montgomery Clift is heavily narrated by its director, Robert Anderson Clift, the nephew of the great actor. (Hillary Demmon also directs.) For this is a filmmaker who wants to make an argument as he sets out to prove that everything you thought you knew about his uncle is wrong. To this end, he doesn’t merely tell the Montgomery Clift story with a different spin but takes on the major sources—especially two biographies—which are responsible for the widely held public image, extracting specific quotations and proving their falsehood. For example, he shows how, when Clift was arrested in New York City for cruising men, gossip columnist Hedda Hopper arbitrarily turned “men” into “boys,” which eventually showed up as a charge of “pederasty” in Patricia Bosworth’s Montgomery Clift: A Biography, a total falsehood.

So, myth number one: that Clift was a closet homo who took pains to hide his secret life. Nah. He was quite open about his affairs with men (there were also a few women), and, unlike actors such as Rock Hudson, he refused to compromise and pretend to be straight. Myth number two: that Clift lived a life of quiet desperation, tormented by his sexuality and resembling the dark, brooding characters that he often portrayed. In fact, he was a sociable, fun-loving, even goofy guy, as demonstrated by ample footage to which Robert Clift had access. The auto accident that almost killed him at age 35 undoubtedly took its toll, but he did some of his best work in the last decade of his life (Judgment at Nuremberg; Suddenly, Last Summer). While he undoubtedly abused alcohol and drugs toward the end, he died of a heart attack, not suicide. Recordings and writings prove Clift to be a highly intelligent actor who knew exactly what he was trying to achieve when creating a character in one of his many great roles.

Transpeople are familiar with the problem of whether to reveal or conceal their transgender status in various contexts. But what if the situation were reversed, and someone who was cisgender had to keep up the appearance of being trans? Meet Adam, a straight high school student who’s staying with his genderqueer sister in New York City for the summer and tags along to parties for gender nonconformists of all kinds. Soon enough he falls for a young woman who assumes he’s transgender. For reasons that aren’t entirely clear, Adam doesn’t disabuse her of this misimpression. So, when they decide to start dating, he’s forced to keep up the ruse—even if it means foregoing the very real possibility of losing his virginity.

Having committed this act of deception—or cowardice—Adam becomes a less than sympathetic character whom we’re kind of stuck with for the rest of the film. Perhaps he’s best seen as an entrée into a world of gender fluidity and non-binarism that keeps Adam, and the rest of us, guessing as to the participants’ former or current gender orientation. Indeed labels are conspicuously avoided, though one couple is referred to as “boy Casey and girl Casey.” Adam is a comedy, and it risks ridiculing this “shook-up world,” as The Kinks called it centuries ago (i.e., 1970), whose members often seem to be enacting a studied weirdness that flirts with self-parody. But director Rhys Ernst, who is transgender, avoids crossing this line, having found a way, albeit a somewhat gimmicky way, to present this largely hidden world to a wider audience.

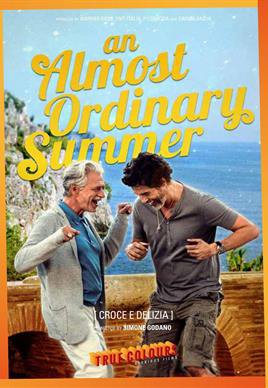

Start with a wildly improbable premise, throw in a huge cast of characters, let them all be Italians, and you’re in for a madcap romp that must set a record for number of words spoken in a 100-minute film. The premise is the impending marriage of two older Italian men, each the head of a large household of wives and mistresses, children and grandchildren, who announce to their respective families that they’ve fallen in love and plan to tie the knot in three weeks. Actually, only one of the men goes through with the announcement, namely Tony, who delivers the news to his family on the terrace of his sprawling seaside villa. His husband-to-be, Carlo, a fisherman by trade, can’t get up the nerve to tell his working-class wife and kids, who’ve been invited to spend the summer in Tony’s cottage on the estate.

In the end this film is less about gayness than about social class. Indeed the marriage announcement telescopes a host of differences that separate the two clans. While Tony’s worldly family goes from shocked to jaded in about five minutes, Carlo’s people remain shocked and try to sabotage the upcoming wedding, led by his twenty-something son Sandro (a “blond Apollo”). One of Tony’s daughters joins in the sabotage and puts the make on Sandro; Tony’s ex-wife shows up, ranting about her children’s inheritance; Carlo discovers that Tony has been more of a slut than he’d realized. It’s all very Fellini-esque, confusing even, as the subtitles can scarcely keep up with the rapid-fire dialog. Every new disturbance seems to throw the wedding into greater jeopardy, which gives the movie its unifying question: can this marriage plan be saved?

The structure of this film may be puzzling and some of the plot devices implausible, but the charisma between its two central characters is enough to draw the viewer into its insular world. The questions will come later; what fascinates us in the moment is the ongoing dance of these two handsome, fortyish men, starting with a series of near encounters in Barcelona before Ocho finally asks Javi up to his apartment, where they have hot sex (interrupted by a humorous attempt to find a condom). They go on a second date; Ocho remarks that Javi looks familiar; Javi replies that they have in fact met before; and suddenly we’re back in the year 1999, twenty years ago, when the two men met and had a fling in the same Barcelona neighborhood.

The fact that director Lucio Castro has made no attempt to change the men’s appearance between “then” and “now” must have been a deliberate choice—just shaving their beards would have done the trick—though it’s not entirely clear what he has in mind: that history is repeating itself, déjà vu style? that time itself is an illusion? The film does play with perception and reality when it proposes an alternate ending that throws the whole story into question. Still, this superficial detail points to what seems to me a missed opportunity. People really do change over two decades, and the stretch from late adolescence to early middle age has got to be the most interesting period in most people’s lives. There’s a moment when Javi reminds his friend that twenty-year-old Ocho wanted lots of kids, but it’s Javi who ended up with a daughter. We note that today Ocho is the top in sex, while earlier he was the bottom. Other than that, there’s little reflection on how things have turned out or even about their earlier affair. The fact that Ocho had forgotten all about it leads us to wonder whether it really happened at all—a more metaphysical question of the kind that seems to interest this director.