THE PAGODA

THE PAGODA

A Lesbian Community by the Sea

by Rose Norman

Sinister Wisdom. 376 pages, $18.95

ROSE NORMAN’S The Pagoda: A Lesbian Community by the Sea is the most recent book in the Sapphic Classics Series, published by the journal Sinister Wisdom: A Multicultural Lesbian Literary & Art Journal. The series’ mission is to reproduce key lesbian texts that have fallen out of print and to resurrect other material from the past that may be of interest to current readers. (Disclaimer: I am an enthusiastic supporter of the journal and applaud the important work of its editor, Julie R. Enszer.)

In keeping with this mission, The Pagoda is just such a work. The book is a well-researched account of a women’s land community that flourished near St. Augustine, Florida, for 22 years. Surprisingly, information about The Pagoda rarely appears in academic literature about women’s communities, and many contemporary lesbian scholars haven’t heard of it. This circumstance is due in part to the intentional secrecy of the community itself. Early in the book, scholar-archivist Rose Norman reports that the Pagoda founders “avoided publicity that would draw undesirable attention to their private enclave.” In a similar vein, when poet Adrienne Rich conducted a writing workshop there four years after the community was founded, the event’s organizer turned down a photographer’s offer to take pictures, arguing that “photography that would lead to publicity after the fact would undermine my aim.” Norman explains that aim as “in line with the Pagoda philosophy of providing a space where lesbians could safely share their creative work and each other’s company.” The relatively obscure position of the Pagoda in the annals of lesbian herstory (here I employ the language of the women’s archival movement) gives Norman’s undertaking particular urgency. In fact, by the time of publication thirteen of the women profiled in the book’s pages had died.

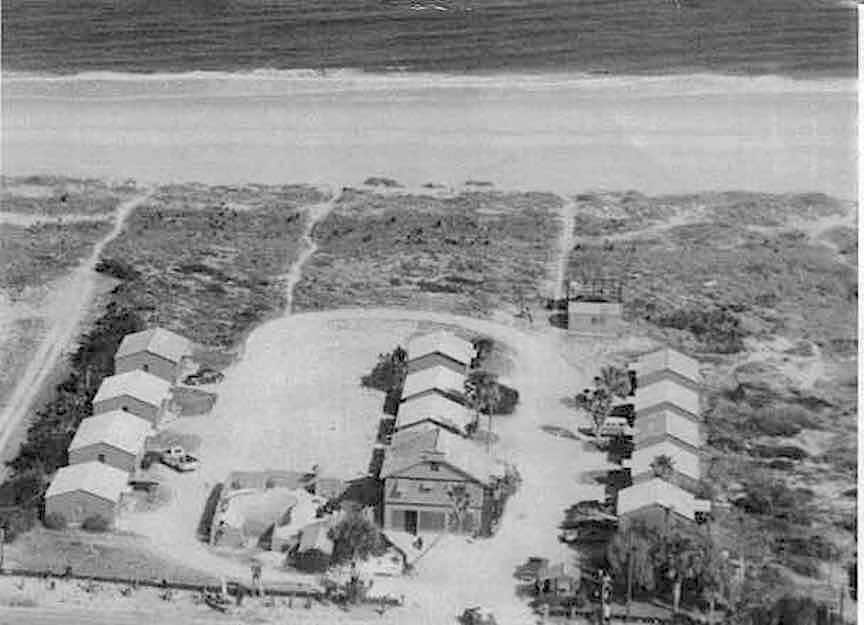

The story of the Pagoda begins in 1977 with Terpsichore, a dance theater troupe composed of two St. Augustine lesbian couples touring Florida with original shows celebrating women. When they discovered some beach cottages that had once comprised a seaside motel called the Pagoda, they seized the opportunity to buy four of them, leased the two-story house in front of them, and began performing feminist plays and concerts. By 1988, what began as a resort or retreat had expanded into a residential community with twelve cottages, a duplex, and three beachfront lots. There was also a cultural center and a swimming pool with an adjacent space called Persephone’s Garden. Norman explains that the Goddess Church—the Pagoda Temple of Love, which owned and managed the cultural center—was a distinguishing feature of the Pagoda in that “it anchored the community while also drawing visitors from far and wide.”

A second characteristic that sets the Pagoda apart from other lesbian back-to-nature ventures is that members weren’t necessarily interested in country living. Rather, as Norman clarifies, “the founders were looking for theater space, not a lesbian land collective, and grew into communal living by various turns of events.” The theatrical component waxed and waned depending on what playwrights were involved and when, but concerts remained a relatively constant artistic expression. Legendary lesbian musicians and singers like Alix Dobkin, Kay Gardener, and Ferron appeared along with local figures. One such musician, Elaine Townsend, recalls that during her concerts, one attendee in particular would talk back and challenge her politics during the concert, shouting from the darkness things like: “I have a problem with that!”

Of course, political differences weren’t always worked out so easily. Throughout its existence, the Pagoda grappled with issues dividing many lesbian communities at the time. Lesbian separatism, a philosophy that dominated many lesbian gatherings during the 1960s, ’70s, and ’80s, remained an abiding principle at the Pagoda. While male tenants were evicted in 1978 and the Pagoda remained a women-only space until a heterosexual couple bought a cottage in 1993, questions like the place of male children, and male relatives and friends in general, dogged the community. As a result, some women withdrew, including one of the founders.

Norman provides a thorough record of the particulars of these and other controversies, including sadomasochism, lesbian battering, and bisexuality. She also focuses on the problem-solving techniques the members employed to work through some of these matters. Chief among these in the first ten years was the Group, a weekly Thursday meeting where members voiced interpersonal issues and other concerns. For those who sought community in another way, there were Sunday brunches where meat was eaten, alcohol was drunk, and politics were discussed. Both of these social mechanisms enabled Pagodans to work through some of their differences and preserve the idea of a women-only sanctuary that originally attracted many of them.

Norman describes a shift in the life of the Pagoda with the purchase of more cottages and an expansion, resulting in the formation of the North Pagoda Land Association, a separate cottage association with its own rules. The two women who initiated this move had explicitly political motivations, having arrived at the Pagoda to do a racism and classism workshop and then buying four cottages. Dubbed by Norman “The Growers,” Marilyn Murphy and Irene Weiss were a power couple who brought new energy to the Goddess-centered gatherings by adding study groups, political workshops, photo exhibits, and performances. Coincidentally, in the year before their arrival, Morgana MacTeer, a founder and the spiritual leader of the community, began to have dreams of moving to the mountains. Soon after that, she bought a cottage in Alabama and began shifting allegiances to what would later become Alapine, a women’s community in Alabama. “The Growers” section of the book covers 1988 to 1995, the time of residence of Marilyn and Irene. (Norman uses first names for Pagoda residents throughout.)

The community’s new direction resulted in a division between North Pagoda and Old Pagoda. This physical distinction was also ideological in that the new North Pagoda residents disdained the original founders’ principles of feminist spirituality and therapy. Norman aptly chronicles the political challenges and failures during this period, including the failure to change the all-white constituency of the community. During the entire life of the Pagoda from 1977 to 2016, only two people of color lived there.

In the penultimate section of the book, titled “The Reclaimers,” Norman marks the beginning of the Pagoda’s decline. In 1995, civic opponents finally prevailed, resulting in a new bridge that brought traffic right to the entrance of the Pagoda. Besides causing car crashes into the gates and cottages, the bridge brought development and the beginning of the transition from a hippie beach to an upscale development. Norman observes of the bridge: “It was a very literal reminder of how alarmingly fragile their small enclave was, and how easily invaded.” Climatic disruption also occurred in the form of wildfires in July 1998 that hurt business, though Norman clarifies: “Pagoda women disagree about whether the wildfires were the tipping point in Pagoda finances.” The third blow came in 1999 when Morgan announced by letter that she was moving the Temple of Love to her new location in Alabama.

“Afterstories,” the book’s last section, records the unsuccessful efforts of four women calling themselves the Fairy Godmothers, Inc. to save the Pagoda. After trying for five years, the time frame the women had set for themselves, the group concluded that the property was just too expensive to maintain. Most members had dispersed by then, some to the Alapine community in Alabama. Norman describes the circumstances that led to the Pagoda’s dissolution. “Plagued by financial worries, and living in different towns, they struggled financially and with one another and tenants and neighbors, until they faced the fact that the property had become a burden.” When they put the available land and the former church up for sale, various factors caused it to stay on the market for eleven years. Finally, however, though the Godmothers had valiantly held on for sixteen years, the property sold in 2016 to a male “old surfer hippie” who owned properties in the area and hoped to live there.

In reflecting on the last years of the Pagoda, Norman wisely reframes the question from “Why did it have to end?” to “How did it last for so long?” One response is unquestionably its offer of sanctuary in difficult times. The author offers the useful historical reminder that “in the 1970s and ’80s, coming out could mean losing your job, your family, even custody of your children.” She provides concrete examples of Pagoda residents who had undergone such discrimination. One woman had been suspended from her high school teaching job in Georgia when her lesbian identity became an issue. Another had lost her job as the state coordinator for battered women’s services in Vermont due to homophobia about her lesbian identity. Norman captures the spirit of healing and community in other contexts as well:

When mica (Meri Furnari) had knee surgery and was incapacitated for six months, the community took care of her, “visiting, bringing food, and cheering me up and rooting me on.” When Garnett Harrison visited after fleeing her home state of Mississippi in fear of her life, she found sanctuary, healing space. When resident Emily Greene experienced serious emotional problems from her work as director of nursing at a local nursing home, Pagoda women brought her mother and sister from Massachusetts to visit and got Emily professional therapy.

While the healing spirit that pervaded the Pagoda was one reason for the community’s longevity, another was the pleasure of living in a community at the beach. Norman quotes one resident as saying: “Women came for the beach and the concerts; they stayed for the community.” Musician June Millington captures the magical spirit of the place in her reflection that “It was like being in a conch shell or something. And you could hear the echoes resounding from all time, really, if you just listened.” That feminist spirituality was a key feature of the early years is reflected in the Pagoda’s joyful motto that also summarizes life there: “Every day there is a song, every night a gift of love, every moon a celebration.”

Rose Norman has spent a decade researching this book, for which she collected a “mountain of interview material,” as is evident from the breadth of her coverage and scrupulous attention to detail. While some readers may feel unnecessarily burdened by information involving easements, quit-claims, taxes, and so forth, she is not shy about sharing this information freely, presumably for the benefit of future archivists and historians. Similarly, I respect her gesture of naming all the participants of the Pagoda over the years, but I have to admit it can get confusing. The book is admirably thorough, providing ample footnotes, lists of plays and concerts, and interviews. There’s a chronology, a section of brief biographies of Pagoda women, and an excellent index. These features are invaluable tools for future scholars. On balance, The Pagoda represents an important contribution in the effort to write this episode into the record of lesbian herstory, a place it where it certainly belongs.

Anne Charles lives in Montpelier, VT. With her partner and a friend, she co-hosts the cable-access show All Things LGBTQ.