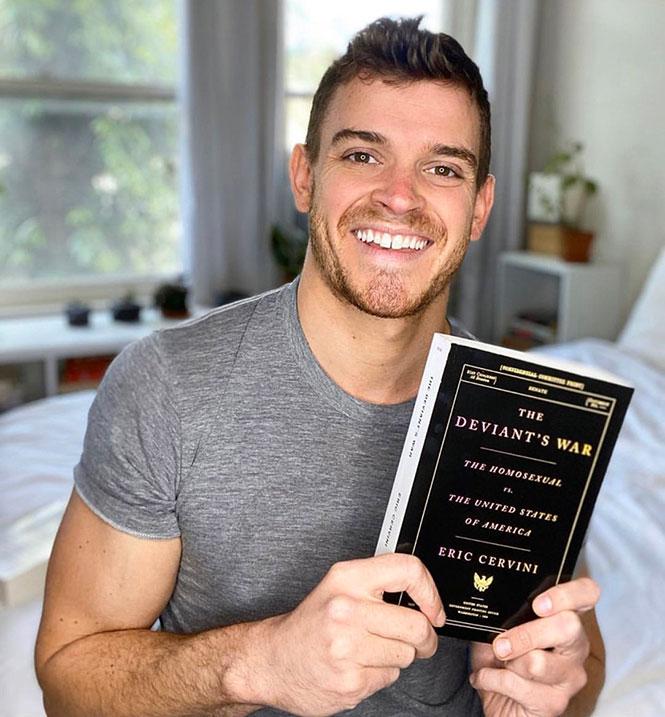

ERIC CERVINI is the author of The Deviant’s War: The Homosexual vs. the United States of America, published this year by Farrar, Straus and Giroux. The book is both a biography of gay rights activist Frank Kameny and a history of the times in which he lived and organized the first protests for homosexual rights in the 1950s and ‘60s. At press time, the book is listed as a New York Times bestseller, having been selected as an “Editor’s Choice” by that paper.

ERIC CERVINI is the author of The Deviant’s War: The Homosexual vs. the United States of America, published this year by Farrar, Straus and Giroux. The book is both a biography of gay rights activist Frank Kameny and a history of the times in which he lived and organized the first protests for homosexual rights in the 1950s and ‘60s. At press time, the book is listed as a New York Times bestseller, having been selected as an “Editor’s Choice” by that paper.

Cervini earned a doctorate in history from Cambridge University after receiving a BA from Harvard, where he graduated summa cum laude. An authority on 1960s gay activism, he serves on the Board of Advisors of the revived Mattachine Society of Washington, D.C.

This interview was conducted as part of a live, on-line series titled “Zooming through Queer Culture,” organized by Andrew Lear (visit website at OscarWildeTours.com).

Eric Cervini: I’m so glad you started with the acknowledgements. Even though it’s in the back of the book, it’s really the origin story for how I discovered Frank Kameny. Once I looked into him, I found that historians recognized how important he was—foundational historians such as John D’Emilio, George Chauncey, and Michael Bronski. They already regarded him as the grandfather of the gay rights movement, but he didn’t have a biography. I was curious as to why that was the case. I have a few theories, but I think one key fact is that, before Kameny passed away, he sold his papers. That’s really how he survived during his final years. Only later did his papers then appear at the Library of Congress. The sheer volume of his personal papers is just unparalleled. From what I understand, it’s the largest collection of an individual for any lgbtq collection in the world, hundreds and hundreds of thousands of pages of documents.

For people who may not know who Kameny was, he was a Harvard graduate who got his doctorate in astronomy in 1956, just months before the launch of Sputnik. The following year he was quite literally positioned to help create the manned space program. This was two years before the creation of NASA. He was working in the army map service alongside Wernher von Braun and could not have been more in demand. He never became an employee of NASA because the federal government, specifically the Civil Service Commission, learned that he had been arrested in San Francisco in 1956 for an indiscretion in a restroom. Once the government learned about this arrest, it barred him from ever working for the federal government again.

At the same time that Joseph McCarthy was exposing alleged communists and fellow travelers, the government was purging alleged homosexuals at an even higher rate. Kameny was one of them, and he was really the first to fight back. He submitted the very first Supreme Court petition for the employment rights of sexual deviants in 1961. Nearly sixty years later [with Bostock v. Clayton County, Georgia], we at last have a Supreme Court decision that protects gay and trans employees all across the country.

JP: This is such a relevant story at this moment in history in light of this Supreme Court decision. Can you say a little more about Kameny’s work life? The purges that were coupled with the “Lavender Scare” didn’t only affect government employment for Kameny, right? Much of what you write about is his struggle to find work. Why was that so difficult?

EC: He called it a form of second-class citizenship, an American apartheid. A historian at Yale estimates that one million Americans were arrested for homosexual activity in the fifteen years after World War II. That ranges from holding hands to sodomy. There was a huge patchwork of local, state, and federal laws that allowed this apparatus of persecution to exist. What’s important to realize is that once you were arrested, that followed you for the rest of your life. So the reason the government learned about Frank Kameny’s indiscretion in San Francisco was because the SFPD, as part of their protocol, would then forward that arrest record to the FBI, which would then be the clearinghouse for those names and that information for all federal applicants and employees.

It was a complex but routinized and efficient system for stigmatizing and persecuting sexual deviants for decades after World War II. As you said, Frank was not allowed to work in the federal government or in the field of astronomy, because in the 1950s and ’60s, in the middle of the space race, if you had anything to do with space, this was a matter of national security. So you had to have a security clearance, and there was no possibility of that. If he applied to work for Boeing or Lockheed, he would have to get a security clearance. And of course, because the FBI and the Civil Service Commission were in touch with the Defense Department, there was no way that he was going to get a clearance. That’s why he was really thrust into poverty, and why he died in poverty as well.

JP: So he was in many ways a reluctant activist, right? He kind of fell into this role. How would you characterize his political activism once he had really embraced it?

EC: Well, I think one thing that historians have long recognized is that he was responsible for bringing militancy to the movement: the idea that we should not simply be fighting for assimilation or to prove to the straight public that we are just like them. The Mattachine Society in California tried this approach—by organizing blood drives or creating charity events or just trying to perform respectability (though respectability was something that Kameny utilized). It was much more about fighting back. We needed to go on the offensive. That could mean litigation, which was his first action—suing the Secretary of the Army. When that failed, he created the Mattachine Society of Washington, which was essentially the first gay civil liberties organization in D.C.

The very first thing that he did—which I think historians have overlooked—was to create a legal organization. This was not just a matter of him going out and picketing in front of the White House. It was very much to create what the Civil Rights movement had in the NAACP, what other groups had in the ACLU. Gay rights was not yet a valid civil liberties issue. So he was the one to say, Okay, we’re going to create an organization to attract other proud plaintiffs, as I call them. So he started recruiting them and systematically beginning a multi-pronged attack, specifically in courtrooms across the country, where he also was declaring that homosexual activity was a moral good. Thus the notion that “gay is good” began, not as a slogan in 1968, but as a piece of legal argumentation in 1961. That’s a big piece of this story, that Pride didn’t just begin with Stonewall. It didn’t even begin with “Gay Is Good” in 1968. It began much earlier as a political and legal tactic stretching all the way back to 1961 and his original dismissal in 1957.

JP: In your book you implicitly question the pre-eminence of Stonewall, the belief there was nothing until Stonewall came along and catalyzed the whole setup of political activities. How do you see this book fitting in with that story as it has been told?

EC: I think most Americans, when they think of the birth of gay rights, think of Stonewall. Historians have done a good job of saying: “Wait a second, let’s talk about Harry Hay, Frank Kameny, and the other activism that was occurring.” But they still fall into the trap of thinking that the strategy of coming out as a political tool was an invention of the late ’60s.

What I would posit is that this is a story of continuity, of Frank Kameny making a claim of moral goodness, which was completely unprecedented prior to 1961, and making that claim openly, as himself, not as “anonymous” when filing the lawsuit as Kameny v. Brucker, the Secretary of the Army. His aim was to disprove the rationale of the purges, because how can you be blackmailed by Soviet agents if you’re open to the world and The Washington Post is publishing stories about your gay lawsuit? So I like to tell a story of this continuous thread of what I argue is an early iteration of Pride, stretching from that first Supreme Court petition in 1961 all the way through, and beyond, Stonewall.

JP: The book is a biography of sorts, from Kameny’s dismissal to his death, but really it’s not. There’s a bigger story that you’re telling here. How did you come to organize the book in this way?

EC: It started with my Harvard senior thesis, and I went into this wanting to tell the history of the Mattachine Society of Washington, which existed from 1961 to ’71. That’s the only story I wanted to tell, but the Mattachine Society of Washington was very often synonymous with Frank Kameny. What you quickly realize is that you cannot tell Kameny’s story without also telling those of Bayard Rustin, Del Martin and Phyllis Lyon, and all of the other figures who interacted with Kameny. So, while it may be easier to market the book as a biography, I really see it more as a story of America in the 1960s and how different movements interacted with one another. Kameny provides a useful narrative device through which we can understand the rest of the country and track his evolution as an activist alongside the evolution of the movement and also of the country.

JP: One of these intersections was with the Civil Rights movement; another was with the feminist movement. Kameny was trying to mirror some of that activism that they were engaged in. How integrated was that effort; how connected were these different activities?

EC: It’s a great question. It’s something that a lot of people have been talking about, and you see it on television and social media: this idea that the first pride event was a riot, for example, and that people of color were the ones on the front line, putting their bodies on the line, especially trans people of color. I think focusing on that one night or series of nights actually minimizes the role of the Black Freedom movement, because in order to tell Frank Kameny’s story, you also have to tell the story of the entire Civil Rights movement going all the way back to Montgomery in 1955 and understanding why Rosa Parks was chosen as the figure to be the model of morality and to be the victim, when in reality she was the secretary of the NAACP and planned it all along. Frank Kameny saw that, and he was very explicit about it. He was self-consciously saying: “I am going to translate what the Civil Rights movement has already done, and done very well, and bring it to the Homophile movement.”

On the other hand, he still had this notion that we needed to project that we’re just like straight people. We’re not like those unwashed mobs, the antiwar movement. And so you have these conversations, but they’re very self-aware that it’s a short step from “Black Is Beautiful” to “Gay Is Good.” Every step of the way for a decade and beyond they were borrowing from the Black Freedom movement. It’s something that we need to recognize now, especially as we look at the photos and see the Homophile movement was really white, and you look at the photos of today and pride marches of today—pretty white. And so I think it raises a lot of questions about what should we be doing now in this moment, especially in the realm of Black Lives Matter.

JP: After Stonewall, the Gay Liberation Front (GLF) and the Gay Activists Alliance (GAA) came along and said: “We need to radicalize. We need to see our fight alongside other groups.” I love the parts where you talk about Kameny’s rules for how to dress while picketing: women in skirts, men in suits, even though it’s 100 degrees outside. By the late ’60s, this approach to activism really conflicted with the younger generation’s more radical sense of gay rights. Does that account for why the Mattachine kind of lost the historical moment?

EC: Absolutely. And I think it’s a bit of a tragedy, because Frank was so ahead of his time in the early 1960s. Finally he was able to persuade the rest of the movement to catch up with him and to actually march and demand change rather than hope we’ll eventually get there by using psychiatrists and attorneys as proxies. Unfortunately, he was unable to adapt. And that’s why more people don’t know his name. It’s why Mattachine Society Washington has been a footnote in history. And it’s why we know about the GLF and the GAA, because they were the ones who came in and replaced the Mattachine. People like Craig Rodwell said: “Your dress code is holding our movement back.”

And that’s the true power of Stonewall. It sent a message, just as the 1968 Democratic Convention sent a message to the SDS [Students for a Democratic Society], which exploded in size immediately after that. Well, the same thing happened at Stonewall. It sent a message that finally homosexuals were ready to fight. And so there was a big migration from the antiwar movement and women’s liberation—people who were already fighting against other injustices—flocking into what had been the Homophile movement. Frank didn’t quite adapt. On the other hand, part of the reason is because he had been so successful up until then. A big part of what he was fighting for was to persuade the ACLU and other organizations that gay rights was a valid civil liberties issue. And he was finally able to do that. So I think it’s a bit more complex than just a new generation of activists sweeping away the old. I think if he really had wanted to continue to be a leader within the movement, he would have adapted.

JP: Viewed from a broader historical perspective, what do you want readers to take away from your book in terms of Kameny’s story and the dynamics around activism and how they evolved in the 1960s?

EC: The one thing that I’ve been trying to get into everyone’s mind, whether they read the book or not, is that we borrowed every step of the way. Earlier we borrowed the entirety of “pride” from the Black Freedom movement. And we owe a great deal to trans women of color. One of the stories that I hope people will pay attention to in the book is that of Sylvia Rivera. A lot of people think it’s all about whether she was or wasn’t at the Stonewall riot. Her importance transcends that question. She was the first person in the Gay Activists Alliance to be arrested for civil disobedience. Then she was systematically excluded because she was a “street person,” as the GAA meeting minutes described it, and she was essentially driven out of the movement. I wrote a Time magazine article about how we actually could thank her for gay marriage. What it shows is that those with the least to lose are the first to fight for us—whether it was at Stonewall or afterwards—but they’re also the first to be forgotten.

And so as we celebrate, as we should, the recent Supreme Court decision on employment rights, but that implies that you have employment to begin with. As workers, our rights are now protected, but what about the people who don’t have a job or never had the chance to get a job? Forty percent of homeless youths are lgbtq people. If you’re a trans black American, you’re sixteen times more likely to be murdered [than the average person]. So when you look at the statistics, it tells you what needs to come next. I think the arc of history shows us what we have a moral obligation to be fighting for now.

JP: The book is so deeply researched, filled with footnotes that everyone should read, but also with the many figures who come up, and their fascinating stories. What was the biggest challenge for you in writing and researching this book?

EC: Well, as you probably could guess, I’m much more comfortable in an archive sitting there with the materials than I am behind a computer screen or a word processor. Research and finding documents is what excites me the most, and finding the hidden history or the undiscovered document makes everything click. The hard part is knowing when to stop. It took seven years to write this book, and the hardest part was to know when to trust what I’d found in the interviews I conducted and the documents I examined. I had a half-million word outline, and that was enough. There’s still more history out there that needs to be found. I hope there will be many more books about Frank Kameny and about the pre-Stonewall gay rights movement. I’m excited to see what comes next.

James Polchin, a frequent contributor to these pages, is a clinical professor at NYU. He is the author ofIndecent Advances: A Hidden History of True Crime and Prejudice Before Stonewall (Counterpoint).