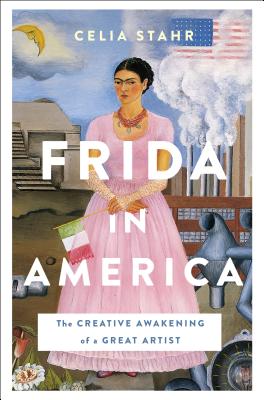

FRIDA IN AMERICA The Creative Awakening of a Great Artist

FRIDA IN AMERICA The Creative Awakening of a Great Artist

by Celia Stahr

St. Martin’s Press. 383 pages, $29.99

ON THE WALL of my neighborhood taqueria, there is a larger-than-life-size photograph of the Mexican artist Frida Kahlo. It’s perhaps a cliché to adorn a Mexican eatery with the image of Mexico’s most popular artist, but for better or worse Kahlo has become synonymous with all things Mexican. One cannot spend a day in Mexico without encountering her iconic image—a dark, androgynous beauty dressed in the costume of the china poblana—depicted on all manner of souvenirs, trinkets, and memorabilia.

This kitschy appropriation is lamentable, because Kahlo was a supremely talented artist many of whose innovative, often shocking, paintings are masterpieces of 20th-century art. Kahlo approached painting with a “fearless spirit,” says art historian Celia Stahr, whose new book Frida in America offers an intelligent and lucid investigation of the artist’s formative years. Unafraid to reject conventional notions of beauty and subject matter, Kahlo arrived in America at a pivotal moment in her career. Until Stahr, no scholar had done an in-depth study of the work Kahlo produced during her time in the United States. Stahr’s biography sets out to rectify this neglect.

Kahlo’s American sojourn began in November 1930, when she accompanied her new husband, Mexican painter Diego Rivera, to San Francisco, where he had a mural commission, one of several mural projects he’d been asked to do in America. She was in her early twenties, full of bravado, spontaneity, and a “provocateur spirit.” While Diego worked on his mural commissions—ones that took him to Detroit and New York as well—Kahlo pursued her own painting projects, pouring into her art a desire “to shake things up.” The paintings she did during her three-year sojourn in this country radiate both fierce pride in her indigenous heritage and a decidedly modern sensibility. Stahr contends that in the American phase of her career, Kahlo “mastered her visual language.”

Kahlo—who would be considered bisexual today—often chose intimate, painful, even taboo subjects for her paintings. One incomplete canvas, Frida and the Caesarian Operation (1931), which was actually about an abortion she underwent, is a case in point. In so many of these early works, she dealt unequivocally with pain, loss, and isolation; she didn’t sugarcoat anything. Because of her cross-cultural family heritage and a debilitating physical disability due to a gruesome accident she suffered as a teenager, Kahlo understood what it was like to be an outsider. Her signature style, Stahr emphasizes, was “one that foregrounds her physical and psychological state alongside important aspects of Mexican art and culture.”

America opened Kahlo’s eyes, and much of what she saw she didn’t like, especially the huge disparity between the high-society set with whom she was obliged to hobnob and the millions of Depression-era poor. As her time in the U.S. went on, Kahlo became increasingly disenchanted with the American scene, writing to her mother: “everything here is pure show but deep down it’s all real shit. … I’m completely disappointed by the famous United States.”

Kahlo’s relationship with Rivera, whom she married against the wishes of her mother, was a complicated and uneasy one. In many ways, they were kindred spirits. They both “espoused the importance of a down-to-earth existence peppered with imagination, creativity, irony, black humor, deep laughter, fantasy and a passion for social justice.” The latter was brilliantly expressed by Diego in his many mural projects, which earned him the sobriquet “Fiery Crusader of the Paintbrush.” Kahlo, too, saw painting as a place where she could express her desire for justice, especially in the face of the double standard applied to men and women.

Kahlo’s relationship with Rivera, whom she married against the wishes of her mother, was a complicated and uneasy one. In many ways, they were kindred spirits. They both “espoused the importance of a down-to-earth existence peppered with imagination, creativity, irony, black humor, deep laughter, fantasy and a passion for social justice.” The latter was brilliantly expressed by Diego in his many mural projects, which earned him the sobriquet “Fiery Crusader of the Paintbrush.” Kahlo, too, saw painting as a place where she could express her desire for justice, especially in the face of the double standard applied to men and women.

But Diego, who was twenty years older than Kahlo, was also a self-absorbed “erotomaniac,” prone to unpredictable outbursts and manipulative behavior. When they married, he was already a major star in the firmament of international art. Laboring under his shadow, Kahlo was often dismissed as little more than the wife of the “master mural painter,” a woman who “dabbles in works of art.” Stahr is fair-minded about Diego even as she spares no details about his philandering and often cruel treatment of Kahlo, who found that managing his mercurial moods was an ongoing challenge. “She vacillated between accepting her fate with Diego as a caged woman … and seeking to be the rebel who wanted the same freedoms that society granted her husband.”

The book crescendos toward the period when the couple returned for a second stay in New York, where Diego worked on murals at Rockefeller Center. His themes of social justice and economic equality, which included a positive image of Communist leader Vladimir Lenin, caused a ruckus. Before the mural was finished, he was handed a check and ousted from the building. The murals were eventually destroyed. The stress of this brouhaha and Diego’s ongoing, flagrant affair with another woman took a heavy toll on Kahlo. When the couple headed back to Mexico in December 1933, their marriage was in a shambles. He blamed her for his failure to get back to work. She fell into a depression. Trying to maintain some sense of emotional balance, Kahlo returned to New York for several months, where she found her creative footing again.

Between 1935 and 1940, she did some of her best work, including Two Nudes in a Forest, a painting depicting lesbian love. In 1938, she had her first solo show, a critical and financial success. In January 1939, she sailed to France for the group show Mexique. One of her paintings, The Frame (1938), became the first Latin American painting to enter the collection of the Louvre. A few months after she returned from Paris, she and Diego separated. By September, she was working on one of her greatest painting, The Two Fridas, which was shown at the monumental 1940 MOMA show Twenty Centuries of Mexican Art.

Stahr’s engrossing book is not only a study of Kahlo’s years in America but also a portrait of the era. Along the way, we encounter a host of luminaries of the 1930s: photographers Dorothea Lange, Alfred Stieglitz, Imogen Cunningham, Edward Weston, and Tina Modotti; artists Miguel Covarrubias, Pablo Picasso, Ben Shahn, and Georgia O’Keeffe, with whom Kahlo had an intense love affair; composers Ernest Bloch and George Gershwin; actor Edward G. Robinson; scientist Luther Burbank (Kahlo did a portrait of him); writer André Breton; and the industrialists John Rockefeller and Henry Ford, both of whom commissioned murals from Rivera.

Stahr, a professor at the University of San Francisco, has brought meticulous research and analysis to this project. She draws heavily on Kahlo’s letters and the unpublished journals of her friend Lucienne Bloch. My one quibble is that she often refers to photographs and paintings that are not included in the skimpy suite of illustrations in the book. Her descriptions of Kahlo’s paintings are superb—including her discussion of the “flirtatious note to Georgia” that constitutes her painting Self-Portrait on the Borderline—but as I read the book, I found myself repeatedly searching on Google for an image of many of the pieces under discussion. “Her paintings are her biography” poet José Moreno Villa once said of Kahlo. It’s a shame that, in the interest of keeping costs down, St. Martin’s Press did not give more credence to that sentiment.

Philip Gambone, a regular contributor to these pages, taught fiction writing at the Harvard Extension School for over 25 years.