THIS MARKS the return, after a two-year hiatus, of my annual roundup of films featured at the Provincetown International Film Festival, which I attend each June with my partner Stephen. While not an expressly LGBT festival, there are always plenty of entries that match this magazine’s mission. Here are four.

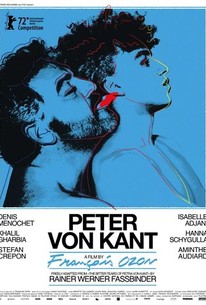

PETER VON KANT

PETER VON KANT

Directed by François Ozon

François Ozon’s new film was billed as a “Secret Screening” at the festival, as all information about it had been embargoed. We knew only that John Waters described it as “a lu-lu,” and that description seems fair enough. To be sure, Ozon’s style in Peter von Kant is nothing like the “low camp” of Waters himself, but the outfits and emotions are so over-the-top that “campy” seems an accurate descriptor. Peter’s personal assistant, for example, is a silent butler who dresses like Charlie Chaplin and robotically carries out his abusive master’s every whim.

The title character is a successful filmmaker who lives in elegant decadence in Paris, where he seems to be having a midlife crisis, bored with his career and mostly drinking and snorting cocaine. In walks Amir on the arm of Peter’s best friend Isabelle, an actress who once starred in his films, and he’s instantly smitten with the adorable, however lost, young man. Amir has no visible skills or experience, which doesn’t prevent Peter from casting him in his next film in a bid to win Amir’s amour. When we rejoin the happy couple nine months later, Amir has become an insufferable brat who appears on magazine covers and barely tolerates Peter, finding him (far from a slender man) physically repulsive.

The film’s structure brings to mind A Star is Born (any version) in which a jaded superstar who’s drinking himself to death discovers an ingénue and launches her career, even as his own prospects are declining. When Amir leaves for good, Peter doesn’t chalk it up to experience (of course) but plunges deeper into drugs and alcohol, culminating in a scene in which his mother, his daughter, and Isabelle converge to witness a meltdown to rival anything that happens in A Star Is Born.

Ozon’s film is based on Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s 1972 film The Bitter Tears of Petra von Kant (based on his play), which had an all-female cast. Just as Petra has been married to a number of men, Peter has apparently been married to at least two women—the daughter who comes home from boarding school is from his “first marriage.” Virtually the entire film is set in Peter’s flat, where a small number of friends and relatives come and go to reveal Peter’s back story and current state of angst. It turns out that Amir, too, is married to a woman, with whom he is still in touch and possibly even in love. The fact that both men have now “gone gay” is not met with any surprise. The idea that gender matters in sexual attraction is treated as a quaint notion in these (satirically observed) postmodern times.

ALL MAN

ALL MAN

The International Male Story

Directed by Bryan Darling and Jesse Finley Reed

If you’re a gay man over forty, chances are you received International Male in the mail at some point in your life. You may have tossed it aside as just a clothing catalog, or you may have dived right in to check out the latest bevy of models. The “magazine/catalog” started publishing in the mid-1970s at a time when Sears and Macy’s were still airbrushing men’s bulges out of underwear ads. Not so International Male, which began to present men in a whole new way—not as clean-cut, generically handsome men but as scruffy guys with muscles and body hair and bulges in all the right places.

Even those who devoured the IM catalog may question the need for a feature-length documentary about it (as I did). But as All Man: The International Male Story shows, IM has a fascinating story to tell, and it may even have played a role not only in expanding the range of fashion options for men but also in shaping ideas about masculinity itself. Sure, some of the clothes it featured were outlandish or even trashy, but they were eye-catching for those who wanted to make a splash, say, at the dance club or on the beach.

IM was the vision of Gene Burkard, who was gay himself and recognized the potential for the gay market. Nevertheless, Burkard decided early on never to use the “g” word or to imply that the models depicted, or the audience targeted, were primarily gay men. The models were manly dudes without a hint of effeminacy or narcissism. Fashionista Carson Kressley points out in the film that here was a spectacle of ultra-butch models wearing some pretty feminine outfits. (Apparently it was often hard for the models, most of whom were not gay, to keep a straight face, as it were, during photo shoots.)

The strategy of avoiding any direct appeal to gay men seems to have paid off. At times up to 75 percent of IM buyers were women buying clothes for their husbands or boyfriends. The upshot is that many straight men started wearing colorful sports shirts and undies that were not tighty whities—and the metrosexual was born. The impact on the gay community was undoubtedly greater still. The IM catalog created a mainstream outlet that presented an image of masculine men who were assumed (or imagined) to be gay—and the clone was born.

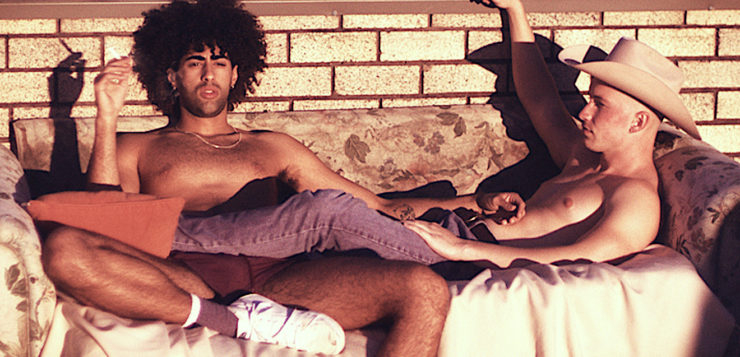

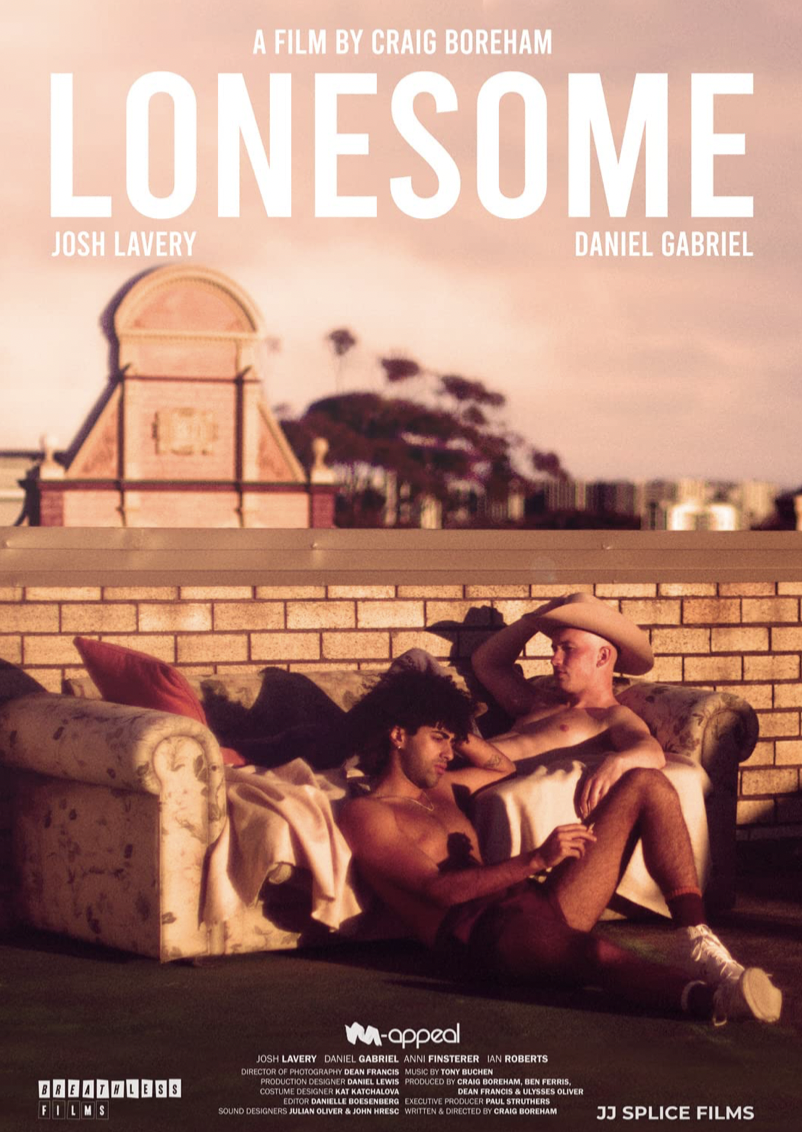

The protagonist of Lonesome is one of those gay men that you would never pick out of a crowd, a taciturn cowboy from Australia’s cattle country who just happens to fancy the dudes. We meet him hitchhiking on a lonesome highway en route to Sydney, having been cast out of his hometown (we later learn), not for being gay but for getting involved with a married man—with dire consequences. “I just took off,” he explains.

Once in Sydney, Casey doesn’t seem to have much of a plan, at first surviving by petty theft, crashing parties, and sleeping on the beach. Grindr to the rescue! He soon meets a guy named Tib who does odd jobs and worries about his immigration status. Tib is an ethnically mixed, street-smart twenty-something who’s immersed in Sydney’s gay culture, while Casey is so white that he’s in constant danger of sunburn. Casey moves into Tib’s flat (it turns out he’s squatting); they shop together at the market; Tib brings Casey to his gig working as a gardener for a lonely middle-aged woman. Things are going too well to last, of course, and they don’t. The break comes when Tib brings home another guy and jealousy enters the room, and then violence, and soon Casey is back on the street. He turns to hustling to survive, but when things head south very rapidly on this front, he reaches out to Tib, who seems to have vanished.

The structure of Lonesome has elements of “Boy meets boy, boy loses boy…,” but it’s such a strange twist on this motif that it remains a highly original and compelling story in the hands of director Craig Boreham. Casey is far from a wide-eyed neophyte in search of love. He is in fact damaged goods, an outcast who’s haunted by the past. Tib, too, is an exile in a foreign land, but his enemies are external ones (Australian Immigration) rather than inner demons of guilt and rejection.

And yet, it would be glib to suggest that their status as “exiles” is what binds Casey and Tib as a couple. What brought them together initially was a compulsive physical attraction that manifests itself in some pretty explicit sex scenes. What sustains the relationship after the sexual intensity drops a notch is something they haven’t quite figured out. Typically this is where “love” comes in: Can Casey and Tib take the big leap?

CHRISSY JUDY

CHRISSY JUDY

Directed by Todd Flaherty

Described by writer-director Todd Flaherty, who stars in the film, as a labor of love, Chrissy Judy begins as the stereotypical show biz movie in which we watch some performers onstage singing or acting their hearts out—in this case a lip-syncing drag act—and then we meet them in their dressing room bitching about the small audience and lousy tips. But once Chrissy and Judy take off their makeup and wigs, we realize that these are not your standard aging performers whose act has seen better days but instead two young, good-looking guys who are best friends (but not boyfriends) and who take their drag act seriously. They live together in New York City and occasionally travel out to Fire Island, supporting each other in their erotic escapades.

The fragility of this arrangement becomes apparent when Chrissy starts to get serious about another man. The rest of the film is mostly about Judy’s efforts to come to terms with Chrissy’s departure and to reinvent himself as a solo act. (Both guys use their drag names in everyday life.) Chrissy moves to Philadelphia to be with his new beau; Judy, already a three-martini kind of gal, visits Philly, gets drunk, and makes a terrible scene. He loses his New York apartment and heads to Provincetown for the summer, where he does a turn in Ryan Landry’s Showgirls revue while working as a houseboy.

In the end, this is a film about friendship—specifically gay friendship, which includes a dimension that’s largely absent from straight buds’ bonds. The latter may banter about women and even go out on the prowl together, but if one of them starts dating someone, the other guy is unlikely to be jealous of the girlfriend or to try to sabotage the relationship (as Judy does). Judy and Chrissy may not be boyfriends, but they could be, after all, and it seems unlikely that they never fooled around at some point (they are gay men, after all). Indeed I suspect many viewers are secretly hoping that the two will get together and end the misery. On second thought, given their shared preference for one sexual position over another (or under another), that probably wouldn’t work out either.