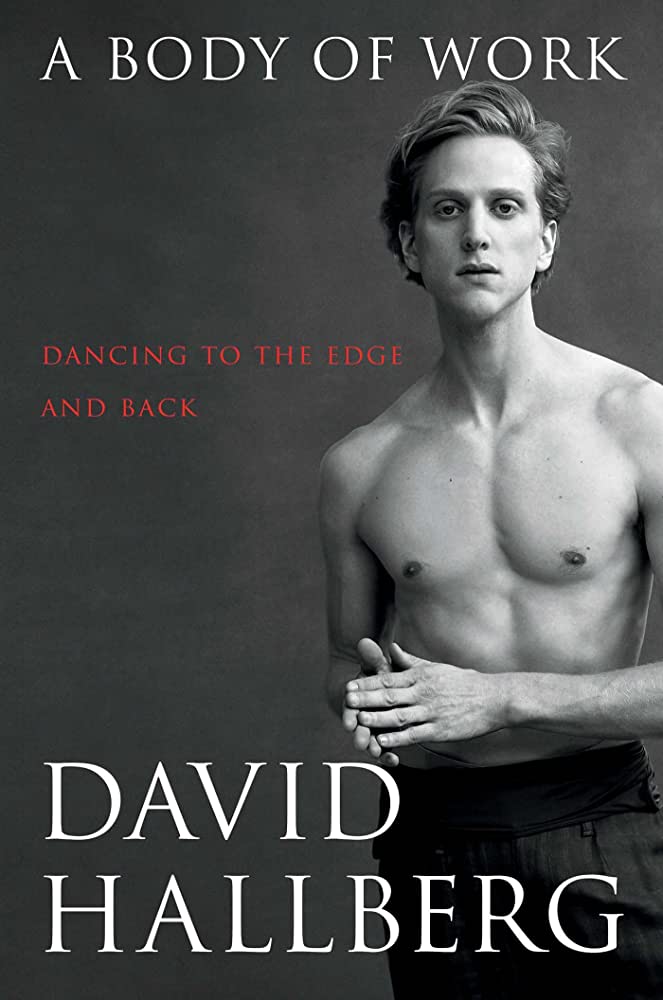

A Body of Work: Dancing to the Edge and Back

A Body of Work: Dancing to the Edge and Back

by David Hallberg

Touchstone Books

432 pages, $28.

IT IS to David Hallberg’s credit not only that he has written a very thoughtful and substantial reflection on his career as a dancer, but also that the career itself has consisted of several highs and lows rarely experienced by other dancers in their typically short careers. Hallberg was the first American dancer to join the Bolshoi Ballet in Moscow. He became a premier danseur there in 2011 while continuing to perform in the American Ballet Theatre, the company he had always dreamed of belonging to, having joined in 2000 after a hideously traumatic year being patronized and bullied at the Paris Opera Ballet School. (His audition for a place there at age sixteen is a truly rewarding find on YouTube).

A Body of Work is a lovely title, suggesting not only the triumphant moments that Hallberg’s realized but also the many challenges that he, like most ballet dancers in this cruelest of crafts, has faced. Chief among these was the deeply serious ankle injury that saw him retire from the Bolshoi after three seasons and found him undertaking radical—and remarkably successful—physiotherapy for well over a year in Melbourne. The title also refers clearly to Hallberg’s inner demons, which, during a period of acute despair, led him suddenly to start smoking, as well as to demand that a barber shave off his golden locks, which were needed for his performance. When the ankle gave out for a period, Hallberg gave up.

The price paid is far from uniquely physical, however. For one thing, as Hallberg confesses, a career in dance is perversely infantilizing in many ways:

Though we become professionals at an early age, we paradoxically remain juvenile in many aspects of our lives. Our schedules are dictated to us, ballets are chosen for us, our touring schedules are arranged by others. Our conversation revolves, for the most part, around the ballet we’re learning, the ballet master we’d rather not work with, the performance we wish we could give or the one we already gave. Our colleagues are not only our friends; they become our husbands, wives, one-night stands, occasional enemies, enduring affairs. For dancers throughout the world, all of life seems encapsulated within the confines of their own companies.

Thus all the dancers in Swan Lake could be said to resemble the ever-tormented and confined Princess Odette. They are almost universally presented as pampered little princes and princesses, people who receive relatively few “reality checks” from the real world.

The pressure-cooker environment is exacerbated—unlike the situation for actors or singers—by the inevitability of a short career. Hallberg is now in his twilight years as a performer; he will soon turn, or be turned, in another direction. The intense pressure has always led to melodrama and explosiveness offstage to rival the fireworks onstage. Sergei Polunin, the Ukrainian “bad boy” of contemporary dance, quit London’s Covent Garden at age twenty, just two years after becoming its youngest ever principal. More shocking still was the sulfuric acid thrown at the Bolshoi Ballet’s artistic director Sergei Filin—the man who had persuaded Hallberg to join the company—in January 2013. A frustrated soloist, Pavel Dmitrichenko, was subsequently convicted of organizing the attack—which left Filin severely burned on his arms and face and 95 percent blind—and sent to prison. Hallberg had danced with him and finds the crime and its motives unfathomable.

Anyone interested in more about these scandals, however, may be better off reading Simon Morrison’s 2016 account Bolshoi Confidential. It isn’t Hallberg’s style to gossip, and clearly he dislikes speaking ill of anyone. He mentions only in passing the fact that another of the frustrated Bolshoi faction, Nikolai Tsiskaridze, while being polite to Hallberg’s face (“my Adonis,” “my little baby”), had told the Los Angeles Times: “I like David very much … and respect him as a dancer, but [his dancing at Bolshoi]is an insult to the entire Russian ballet, a demonstration of indifference to the rich Russian tradition and culture.” Russian nationalism, we learn, is very catching. Tsiskaridze did not say so exactly, but he implies that no American could adapt to the Bolshoi or shine in its productions. Hallberg turned this challenge into an opportunity.

While diplomatic in talking about others, he candidly describes his own coming out and the many ways in which his perceived softness, grace, and, yes, effeminacy caused him shame and worry. His peers had made him the object of bullying from his school years on. One poignant anecdote recounts how they chose to ensure that he “officially smelled like a girl” by pouring an entire bottle of “cheap drugstore perfume” over him. And we also get a glimpse of his first teenage passion in Phoenix: for Jack, the only other boy he knew who was drawn to dance. Although their relationship soon grew cold, they were both saved from bullying by—what else?—the promise of “fame” and enrollment in the newly opened Phoenix School of the Arts.

Hallberg doesn’t write about his adult relationships at all. This may simply be because the career velocity he experienced largely prevented him indulging in much of anything other than work. He writes little about Russia either—notable in light of the state-sponsored intolerance that reigns today—except to state that he never experienced this attitude and never felt at risk at the Bolshoi. He must have lived in a bubble. In any case, relations with the Bolshoi were apparently severed in 2017 simply because, after his recovery from an injury, he longed for a more sustainable work–life balance. No other reason is given.

This was, though, just months before the Bolshoi announced the sudden postponement (initially, cancellation) of a long-planned ballet about the life and work of Rudolf Nureyev. The quality of the dancing was officially blamed, but one principal dancer let slip the truth: that the Bolshoi was succumbing to self-censorship, encouraged by its political overlords. Oddly, the ballet was finally rescheduled and opened in December 2017—but its director, Kirill Serebrennikov, could not attend the premiere. He remains under house arrest for alleged embezzlement, a charge that his Bolshoi supporters think was invented.

As Morrison explains, the Bolshoi dancers have long been “groomed” for political advantage. The company is today a globally effective and influential tool used by Vladimir Putin to perpetuate a set of positive conceits about Russia: that its performers, both male and female, outshine those of any other country, that their athleticism, virtuosity, and stamina reflect comparable virtues in Russian society. Hallberg is thrilled to have had his hand shaken by Putin’s Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev. For his Russian peers, too, this simply means that he has made it as a dancer, nothing more.

The Bolshoi dancing style is, as Hallberg carefully explains, as it always was: heavy and Asiatic, more Dionysian than Apollonian for its men. Hallberg began, and in Paris and the U.S. remained, at the extreme of Apollonian expressiveness. Long-limbed, sinewy, and precise, he dominated the stage by his apparent lightness of being. Russian choreography tends toward the “earthly” or Dionysian opposite. This meant, for Hallberg, that the Bolshoi opportunity forced him to abandon some of his Apollonian style in favor of the Dionysian; and he was always a willing pupil.

The results were mesmerizing, very distinctive, and sometimes slightly odd. There are moments in Hallberg’s post-Bolshoi performances that seem to reflect the incompatibility of the two types of expression. Politically, his appointment to the Bolshoi also had a contradictory aspect in the U.S.: it could be presented as a career triumph, certainly; but it could not be overlooked that Hallberg was working for its old Cold War foe. Russia was obviously thrilled at the opportunity to present Hallberg as the “anti-Nureyev”: a counter defector, going from West to East—and, intriguingly, exactly a half-century after Nureyev had bolted for freedom, on impulse, at Le Bourget Airport, Paris.

The book’s most striking claim, however, is worth repeating. Hallberg praises his first teacher Mr. Han for his very un-American teaching style. Han told it like it was rather than “dousing” his pupils “with positive reinforcement” simply for trying. Hallberg succinctly and persuasively argues that a widespread over-generosity in the American educational system effectively acts against excellence ever shining through, because—unlike in the hierarchical if brutal pedagogic models of France and Russia—American ballet students invariably end up “all too aware of their strengths and far too unaware of their weaknesses.”

Hallberg proved exceptional because he refused to accept this praise even when some teachers offered it. There are even traces of masochism in his determination to seek out his own shortcomings. For Hallberg, knowing how one fails is essential, since, “when a dancer cannot hear the truth, he ceases to grow as an artist.” There is obvious bravery in his relocating first to Paris as a barely pubescent teenager (with zero French) and later to Moscow as a seasoned adult (with zero Russian). In the first case, he tells a wonderfully disarming story of just how provincial the boy from South Dakota was: “Like many who have never left the nest, my naïveté was immense. Before I left, I bought a year’s worth of shampoo and deodorant to take with me because I didn’t think I could buy those necessities in France.”

Richard Canning contributed an essay on New Zealand dancer Douglas Wright’s memoir Ghost Dance for an anthology he edited, 50 Gay & Lesbian Books Everybody Must Read (2009).