RED CLOSET

RED CLOSET

The Hidden History of Gay Oppression in the USSR

by Rustam Alexander

Manchester Univ. Press

265 pages, $26.95

IN 1932, a 25-year-old Russian-speaking journalist from Scotland named Henry Whyte moved to Moscow to take a job at an English-language newspaper called Moscow News—in part because he was a Communist, in part because he was a homosexual, and there was no law against homosexual acts in Russia like the one in his native country. At that time, homosexuals in Moscow found one another the way they had in the 19th century—in public parks, toilets, and bathhouses, which was how Henry met a man named Ivan. Attracted to one another, they began taking long walks together around the city, until one day Ivan disappeared. Upset, Henry tried to find out what had happened to him, and in his research discovered that the Soviet Union was no longer the lodestar of free love it had been under the Bolsheviks. Its new leader, Joseph Stalin, had secretly passed a law criminalizing homosexual acts after his secret police, the OGPU, raided a drag party in Moscow one night in 1933, and the head of the OGPU, Genrikh Yagoda, convinced Stalin that there was a homosexual underground in Russia that threatened the stability of the state.

Until then, homosexuals had been tolerated in the government as long as they did their jobs well. Some Russian doctors were even ahead of the West in considering homosexuality a natural sexual variant, not the “mental illness” that American psychiatrists deemed it at this time. So, after discovering the new law, Henry Whyte wrote a letter to Stalin asking for clarification on the subject. (Lots of people wrote Stalin letters. His staff sifted through them and chose the ones Stalin saw.) “Dear Comrade Stalin!” it began. “Although I am a foreign communist, I think you, the leader of the world proletariat, will be able to shed light on the question, which is of great importance for a great number of communists both in the USSR and other countries of the world. The question is—can a homosexual be a member of the Communist Party?”

This letter, one of the many fascinating documents reproduced in Rustam Alexander’s deeply researched book, Red Closet, went on to present Whyte’s reasons for answering in the affirmative. In his view, it was capitalism that was “inherently against” homosexuality because capitalist states required manpower for its wars. But Stalin never answered. Instead, the Soviet dictator scrawled on the letter “idiot and degenerate,” and had it sent to the archives. Henry Whyte left Moscow for good in 1935, and the reader of Red Closet, alas, never learns, any more than Henry did, what happened to Ivan.

What happened to Ivan, and countless homosexuals like him, is the subject of Red Closet. Rustam Alexander’s first book, Regulating Homosexuality in Soviet Russia: A Different History (1956-91), was based on his doctoral thesis and written for fellow scholars, but, he says in the preface to his new book, he has chosen to write this one for the general reader, because he wants this story to be known by a wider audience. Interviewing homosexuals in Russia, he claims, is difficult, because most are too ashamed to speak on the subject, and the rest are deceased. So, along with secondary sources, he has taken material he found in the Moscow archives—police reports, letters, narratives of Russian men trying to be “cured” of same-sex desires by doctors in a country where most Russian people felt that such “perverts” should be shot or exiled to Siberia—and either paraphrased them or presented them as they were written by the participants. And they are spellbinding.

After Stalin died—lying alone on the floor of his bedroom, because his staff was too terrified to knock on the door—his successor, Nikita Khrushchev, commissioned a report exposing his predecessor’s crimes (which included mass starvation in Ukraine). But homosexuality continued to be illegal. In fact, one of Khrushchev’s worries was that freeing prisoners from the Gulag (the network of prisons that Stalin had filled during his reign) would flood the country with homosexuals. Khrushchev’s main effect on the lives of homosexuals was his effort to improve the lives of the average Soviet citizen by building affordable housing, which freed urban homosexuals from their dependence on finding partners in public toilets. But nothing else improved, and Khrushchev’s successor, Leonid Brezhnev, inaugurated a period of such corruption, cynicism, and stagnation that the gay liberation movement occurring at that time in the West was unimaginable in Russia. It wasn’t until Mikhail Gorbachev—whose policy of “perestroika” (restructuring) and “glasnost” (openness) led to the dissolution of the Soviet Union—that homosexuals had hope.

Each of Red Closet’s chapters is presented chronologically by dictator (Stalin, Khrushchev, Brezhnev, Gorbachev), and each begins with a brief overview of the socio-economic situation in Russia when these various dictators assumed power. But the chapters themselves are mostly devoted to the stories of individuals whose records Alexander found in the Moscow archives. Many of these are painful to read, especially the transcripts of patients hoping to be “cured” of their homosexuality. The shame, alienation, fear, and self-loathing are all too familiar—even now, to an American reader—though the Russian version seems worse. The USSR was a culture in which, as Alexander puts it, Russian men “did not want to fall in love with another man. Indeed, they never allowed themselves to think love between men was possible. They did not wish to identify themselves with their desire—since society was telling them that it was either a crime, a pathology, or a perversion.” So many of these transcripts—doctors’ notes, patients’ narratives—end with Alexander noting that we have no idea what happened to these men; they simply vanish, like Henry Whyte’s friend Ivan. Where did Ivan go? Was he shot, imprisoned, sent to Siberia? Did he return to some rural village, marry, and have children? Where did any of these young men desperate to be normal, unafraid, free of suspicion, end up? Like so many figures in Russian history, they are lost.

During the Brezhnev and Gorbachev periods, the West was changing its laws and attitudes toward homosexuals, but Russia was not. Even though Alexander carefully provides the dates on which homosexuality was decriminalized in former Soviet satellite countries, we’re not told how conscious individual Russians were of what was happening outside its borders, or what effect this had on individual LGBT Russians. The saying goes that Russia never changes. The U.S., you might say, is based upon change. The Stonewall Riots had no immediate effect on Russia—although in the last stages of perestroika, when the Soviet Union was falling apart, gay people began forming organizations and publishing their own newspapers, and in July 1991 an International Gay and Lesbian Symposium and Film Festival took place in Moscow and Leningrad. But it was not until 1993 that Boris Yeltsin, Gorbachev’s successor, “facing pressure from the Council of Europe,” repealed Article 121.1, which had criminalized consensual sex between men.

What’s so remarkable about the depth and intensity of Russian homophobia is that even after the anti-homosexual law was repealed, when gay activists like Masha Gessen tried to track down all the people imprisoned for homosexuality in Russia, they found that some prison overseers still refused to free them. Writes Alexander: “When Yuri Yereyev, president of the Tchaikovsky Foundation for Cultural Initiative and the Defence of Sexual Minorities, visited Yablonevka prison with a Western journalist, the prison director stepped outside and screamed, ‘I don’t care what has been repealed. They are still in there, and they will stay in there.’ He never allowed the activists to enter the prison.” In Gessen’s eyes: “The repeal of Article 121.1 fell far short of guaranteeing gays and lesbians equality before the law in the area of private conduct.” And in June 2013 the Russian Federal Parliament, “controlled by Vladimir Putin,” unanimously adopted a law prohibiting “propaganda” of non-traditional sexual relations “among minors.” Putin did this, in Alexander’s view, to “increase his popularity and distract public attention from declining living standards by unleashing a campaign of hatred towards lbgtq people, casting them as a great threat to Russian society on Russian state-controlled television and newspapers.”

But was it only that? It may seem incredible that Putin invaded Ukraine because he’s afraid that Western tolerance of transpeople and homosexuals will infect Russia, but he has said so in speeches denouncing the “godless” West. If Russia still seems to bear traces of a religious, feudal, martial society—with a history of a society based on conquering its neighbors, “gathering” land, crushing its enemies—what could be worse than a man attracted to other men? A recurring motif in Red Closet is the Russian scorn for unmanly men. As far back as Anna Karenina, one finds a scene in which the virile Vronsky, on the day of his disastrous horse race, runs into two effeminate fellow soldiers back at the officers’ club. Even Tolstoy, apparently, found queens repellent.

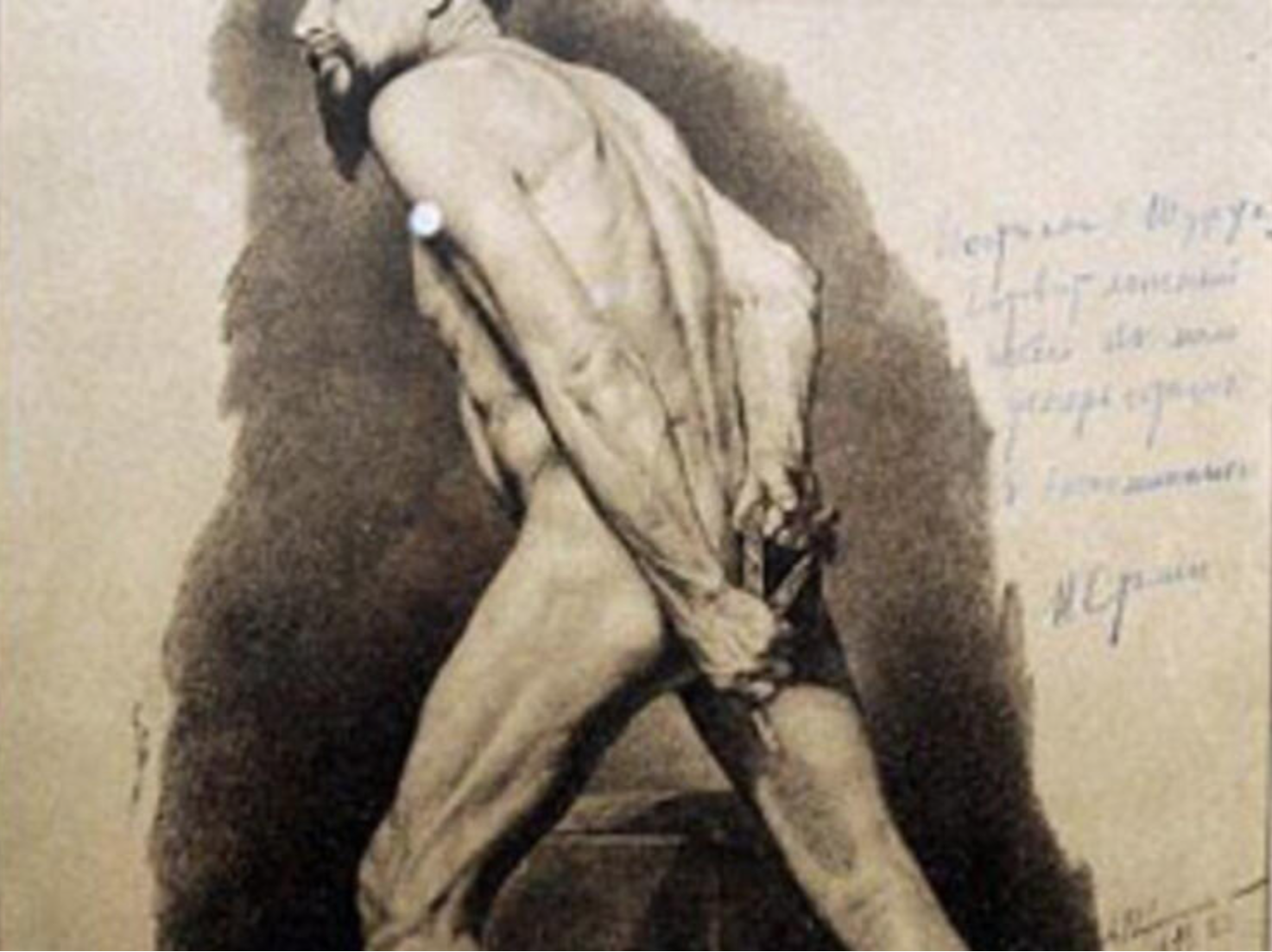

And yet, Russia has a tradition of late 19th-century artists like Konstantin Somov, who have left us with stunning paintings of the male nude. In 2009, an art gallery in Moscow opened a show of nineteen prints of naked men on which Stalin had scrawled commentary in his old age. Apparently this may have stemmed from a Bolshevik custom of drawing cartoons of each other as they sat deliberating and then passing the drawings around under the table—quite like schoolboys. Stalin, it turns out, was among many things an enthusiastic editor who loved to wield his red and blue pencils. On one list of people jailed by the forerunner of the KGB, he simply scrawled the words: “Execute everyone.” On the prints of male nudes he perused at age seventy he scrawled all sorts of things: jokes about masturbation and intercourse, even—the eeriest—messages to former colleagues he’d had executed. “Radek, you ginger bastard, if you hadn’t pissed into the wind, if you hadn’t been so bad, you’d still be alive,” reads one caption, placed alongside a muscular nude drawn from the back by Vasily Surikov, a famous 19th-century Russian artist. Psychologists who were shown these annotated prints say they do not indicate repressed homosexual desires, but one cannot help but wonder.

When the home of Genrikh Yagoda, the head of the OGPU who convinced Stalin that he must recriminalize homosexuality, was raided in one of those purges that characterized Stalin’s rule, the police found a collection of four thousand pornographic photographs and movies, “countless pieces of women’s clothing—stockings, hats, silk tights … and even a rubber dildo.” After Yagoda’s conviction at a show trial, he was forced to sit in a chair and watch twenty other Party functionaries shot before he was beaten to a pulp and shot himself. It’s hard to exaggerate the virulence of Russian homophobia. The attitude seems to be that of the father who tells his son, when asked about homosexuals: “Son, these people are freaks, they are ridiculed, it is a horrible and untreatable illness.” When AIDS began, the Russian government immediately classified it as a disease of foreigners and closed its borders against them, until Russian citizens started dying, and even then, the medical treatment was administered with homophobic contempt. “He looks more like an infantile adolescent than a thirty-six-year-old man,” one doctor writes about the man who became Russia’s Patient Zero. “He readily showed himself to the many doctors from the clinic and others who had come into have a look … and in his readiness to expose himself there was something unnatural. … He was complaining in a high-pitched voice.”

“Dear colleagues!” writes a doctor who’s just received his degree. “We, graduates of a medical institute (sixteen men) are categorically against the fight against a new ‘disease’—AIDS! We intend in every way to hinder the research for means of combating this noble epidemic. We are confident that AIDS will destroy all drug addicts, homosexuals and prostitutes in a short time. We are convinced that Hippocrates would have approved of our decision. Long live AIDS!”

It’s breathtaking in its cruelty and malice. But nothing comes close to the irony of the KGB’s disinformation campaign that claimed AIDS had started in a biological laboratory at the Pentagon. The story turned out to be based on an article in The New York Native, and when an American analyst of Russian propaganda met with a group of Russian journalists who had pushed the Pentagon story, he pulled out the issue of The Native in which it had appeared. On the cover was a photo of three men in drag—one in a long gown and cowboy hat, the other two in cowboy hats and jockstraps. When shown the newspaper, the Russians agreed to drop their claims, and as thanks for saving them from further embarrassment, offered the American “a free subscription to the Novosti Military Bulletin, which normally costs $200.”

There is nothing in this book that will surprise people whose opinion of Russian intolerance, illegality, persecution, and prejudice is already very low, but the details, the dates, the voices of the lost, make for riveting reading. Still, it’s jaw-dropping today to read in the April 21, 2023, issue of The New York Times that, according to Russian prisoners captured by Ukrainians, Putin’s regime has been offering prisoners with HIV a pardon and the promise of better anti-retroviral medicines if they serve in combat for six months. As Timur, one of the HIV+ Russians captured by Ukraine, attests, one has the choice of dying slowly (in prison, of ineffective anti-retrovirals) or quickly (as cannon fodder on the battlefield). It’s a win-win for Vlad: he gets troops for his indefensible war, and eliminates infected queens!

Alexander’s book has two strands—the persecution and punishment meted out to homosexuals by Russian society, and the decades-long attempt by a few Russian doctors and psychologists to get homosexuality decriminalized. The invasion of Ukraine brings up the whole issue of the relation between homophobia and what we now call toxic masculinity, exemplified by those photographs of a bare-chested Putin in the outdoors, or his telling one of the mothers who were invited to meet him in the Kremlin that they could take comfort in the fact that dying on the battlefield was better than dying as a drunk. What a vision of the potentialities of a man’s life he has for Russia! But remove Putin and I don’t think you remove Russian homophobia.

It’s telling that Red Closet has been published by a university press in Britain and is written under a penname by a man whose “mum and dad still don’t know what kinds of books I write” and whose hope is that one day Russians will be able to read Red Closet in their native language.

Andrew Holleran’s latest novel is The Kingdom of Sand (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2022).