POLITICS AND POP CULTURE have always played off each other in advertising, and nowhere has that link been more clear than in gay-targeted ads. Over the past four decades, while gay men and lesbians emerged from invisible to marginal to actively courted as a consumer market, advertising has come along for the ride, mirroring social changes, often in surprising ways. Where ads once winked and teased about homosexuality, gayness has risen from subtext to text in marketing.

If the 1970’s were about hedonism, the 80’s about activism, and the 90’s about visibility, the early 2000 years are all about equal participation. The implications of that social shift are immense for marketers seeking gay “mindshare.” I would argue that because of the social and political developments of the last few years, we’re about to see the most profound shifts in gay-themed advertising since the first gay-focused ads appeared in the early 80’s. Just as the debate over same-sex marriage rights portends a new kind of social integration for gay people, advertising culture will undertake its own kind of assimilation of gays—just as it has done for African-American, Asian, and Hispanic consumers through recent decades.

For consumers, this will mean more complete, less divisive portrayals of GLBT people in advertising. Until now, ads targeted to gay consumers have focused on what makes them different. Moving forward, I believe the angle will change, just as it has for other emerging markets, as advertisers begin to focus on people less for their gayness than for their fame, talent, or looks. For marketers, this will mean higher expectations on the part of gay consumers, but more chances to reach them. What will those expectations and opportunities be? Based on what we’ve seen at Prime Access and what we’ve been observing from our Fortune 500 clients, here are some of the trends that we see on the horizon in the coming five or ten years.

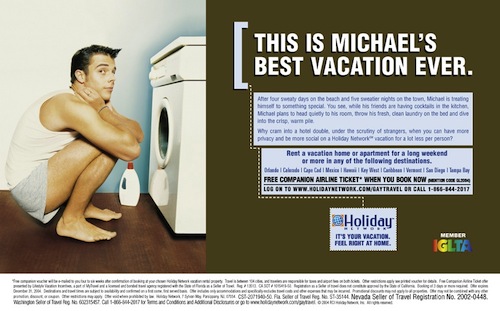

First, advertising can be expected to move past stereotypes, as gay images become increasingly acceptable to non-gay consumers. The breakthrough here was the famous Ikea spot on network TV in 1994, in which an obviously gay middle-aged couple was shown buying furniture together. While this ad exploited to some extent the stereotype of gay men as furniture mavens, the men themselves were presented as “normal” American males (or at least TV’s version thereof). Also, to see the association of gay men with furniture as based on a wholly negative stereotype misses the point. Gay men are perceived as having an expertise when it comes to home furnishing that enhances their credibility as role models for selecting that new dining room set. This point is driven home by the more recent example of the series Queer Eye for the Straight Guy, where five gay men are positioned as experts on a range of personal care and home management issues, and companies pay handsomely for “product placement” that associates their wares with the Fab Five.The use of gay and lesbian images in advertising can be expected to follow the trajectory of African-American representation, which has a much longer history in U.S. advertising. The first marketing efforts traded on broad stereotypes that associated this group with proficiency in food preparation: early examples would be Aunt Jemima’s pancakes, Uncle Ben’s Rice, and Cream of Wheat. Another association for African-Americans has been with cleaning products, and even today there’s a TV spot for Pine Sol that exploits the worst cliché about the sassy “colored” woman. Nevertheless, advertising has largely moved beyond these stereotypes to portray African-Americans in virtually the same range of everyday situations as any other group, visiting a theme park or getting indigestion just like everyone else. Even the field of cosmetics has now embraced African-American images—highly personal products have always been the most sensitive to any sort of negative association—something that didn’t happen until the late 1990’s.

By the same token, marketers can be expected to become more sophisticated and begin portraying gay and lesbian people as plausible experts in a wider range of topics than just fashion or home decorating. For now, a show like Queer Eye is in fact trading on such stereotypes, but it represents the kind of stereotype that has moved other “emerging markets” into the cultural mainstream. Here an evolution can be observed from a negative stereotype to a positive attribute. Thus a classic stereotype of gay men is that they’re overly concerned with their appearance. The flipside of this is an image of gay men as genuinely better-groomed and even better-looking than the average straight guy—and possibly even sexier. The first example of this association was probably the Calvin Klein underwear ads in Times Square way back in the 70’s. These were the first billboards that used sex to sell underwear, and while the models weren’t explicitly presented as homosexual, the fact is that gay men were the main targets of these very provocative ads, which lent them an inevitable homoerotic undercurrent. In a similar vein, the underwear brand 2(x)ist has used gay-typed images right on the label to boost the sex appeal of its product—first in men’s clothing stores in places like Chelsea, New York, and West Hollywood in Macy’s and Bloomingdales. Meanwhile, the retailer Abercrombie & Fitch has been using homoerotic imagery to enhance its hip and youthful image for quite a few years (though the brand has somewhat retreated on this front in response to public criticism).

Increasingly, in fact, gay men are perceived as trend-setters in the realm of personal style, the guys who brought you the hairless chest and the sculpted eyebrow. There’s at least a discernible segment of the straight male market (and their girlfriends) that looks to gay men for direction in personal care and fashion, and this is reflected in the marketing of these products. This is also true to a lesser extent in the area of travel destinations, and has been ever since gay men turned South Beach into a hip spot for straight people, especially the young. (Could MTV have been far behind?) On that subject, it’s also worth pointing out the close association between youth and gay culture. Being gay is strongly associated with being hip, young, and white (the blonder the better), and it remains to be seen whether images of older gay men and lesbians will eventually make headway in popular culture.

What can be anticipated is that the appearance of gay and lesbian couples in mainstream marketing will become less remarkable and more routine. Images of same-sex couples with children, on the other hand, are probably off in the future given societal attitudes on children and the nuclear family. On the other hand, when the target audience is gay and lesbian consumers, companies can be expected to portray same-sex-headed families if they deem it appropriate to their product or service. Thus, for example, Volvo is marketing to gay and lesbian consumers with a two-page print ad that depicts such a family under the heading, “Whether you’re starting a family or creating one as you go.”

Another parallel with the African-American experience is the way in which gay and lesbian celebrities are starting to be tapped to endorse certain kinds of products. The best example is Thom Felicia, the home design maven on Queer Eye for the Straight Guy, who has been tapped by Pier One Imports for a national campaign. This suggests that gays have now overcome one of the major hurdles for celebrity endorsement. At one time companies used African-American celebrities as endorsers only sparingly for fear that their product would come to be perceived as a “black brand.” Clearly this is no longer the case, as African-American celebrities have become some of the most successful commercial spokespeople. Pier One is counting on its customers to understand that Felicia is being trotted out as an expert on home matters rather than as a professional homosexual. As such endorsements become more commonplace, the fact that endorser is gay will become less and less of an issue. High-profile gay men and lesbians who excel in their fields—sports or entertainment, music or art—will gain tremendous ground as viable, effective spokespeople for a wider range of blue-chip brands.

Any reservations advertisers may have about using gay and lesbian images to reach mainstream markets disappear when the target is gay and lesbian consumers, and here the use of celebrity endorsements is well-established. One prominent example would be Martina Navratilova’s association with the Visa Rainbow Card, which has been a major factor in the card’s success. Such endorsements are especially effective where gay identity is important to gay consumers as a brand choice—for example, in areas related to travel, financial services, and other high-income categories, such as fashion, cars, and spirits. These are areas in which the consumer’s gay identity strongly influences their purchasing behavior. For example, when traveling, gay people want to know they’re going to a safe destination where they’ll be accepted and won’t encounter homophobic reactions. Where one’s gay identity mediates purchasing behavior in this way, a celebrity endorsement can provide the sort of reassurance that someone is looking for.

Another area in which gay people often face a high level of uncertainty is in financial services. Two women applying for a mortgage may worry that a bank will frown on their non-normative relationship, or be insensitive to their unique financial situation. (Often same-sex couples do not blend their assets in the way that a straight married couple does.) Endorsements can be useful here because companies know there’s a specific message that gay and lesbian consumers need to hear to reassure them. In addition, celebrity endorsements always come into play when there’s little substantive difference between competing products—spirits are a good example—and image is everything when it comes to product choices. When you buy a drink in a bar you’re telling people around you what kind of person you are.

If “being gay” makes a difference in one’s choice of travel destinations or fashion statements, it has little impact on some product choices. However, there are some categories in which gay people have an unusually high rate of consumption—think skin care—even though being gay doesn’t affect how the product is used or what brand one prefers. These tend to be “parity products” that differ little in performance—and this applies to most mass-produced products—so the marketing focus shifts to non-performance factors such as image or brand. One way to create a brand identity is to develop positive associations with the target group. Thus, for example, American Airlines has captured a large share of the gay market by adopting pro-gay policies, such as a strong anti-discrimination policy for employees and customers, and by reaching out to the community through sponsoring gay events. Studies have shown that GLBT people are unusually loyal to companies that consistently advertise in gay venues.

Perhaps the most important changes in marketing are being driven by technology. Up until recently, advertisers have been largely limited to print media, as broadcast media cannot target a single group, so advertisers trying to appeal to a very specific niche waste a lot of their dollars reaching other groups. But the growth in gay-oriented cable television, satellite and internet radio, and on-line media are changing this situation, and can be expected to do so dramatically as we go forward. Already there’s a gay TV network called LOGO that’s being started up by MTV.

Magazine advertising remains a mainstay for gay marketers given the relative ease of reaching the target market through the self-selection of magazine purchasing. Several mass-marketed periodicals—among them The Advocate, OUT, XY, Genre, Girlfriends, Curve, and Instinct—have been notably successful in attracting mainstream advertisers, and the willingness of large companies to advertise in these journals has been growing steadily over the past decade. In an article for this journal about five years ago (Spring 2000), I conducted a small, unscientific survey of the advertising content in six issues of three magazines: The Advocate (three issues), OUT (two issues), and Girlfriends (one issue). I thought it would be interesting to compare these results with a similar sample of more recent issues of these same magazines (all from late 2004), so I followed the same procedure as before. (Note: Curve was substituted for Girlfriends. Not included in the count were ads in The Advocate’s “Marketplace” section, other than travel destinations.)

And the comparison is striking. While the total number of ad pages in the six issues remained remarkably constant between 1999 and 2004 (at over 250), the distribution of the ads by product category shifted dramatically in some areas. The most striking shift is that cars, which barely registered in 1999, accounted for by far the largest share of ad pages in 2004—clear testimony of the willingness of mainstream advertisers to go after the gay market. Echoing this trend was the large number of appliance ads (including everything from vacuum cleaners to computers) and furniture ads, both categories that didn’t even register back in 1999. Meanwhile, the biggest losers tended to be categories pitched directly to the “gay lifestyle”: alcohol, travel destinations, cosmetics, and cigarettes. Websites dropped off due to the bursting of the “dot-com bubble.” Clothing and HIV drugs both remained strong (though most of the clothing ads came from one issue of OUT.)

Finally, it should be noted that each issue of OUT magazine, which appeals largely to men, accounted for about one-fourth of the total advertising page count, while Curve, the largest-circulation magazine for lesbians, accounted for less than five percent (at 64 versus twelve pages per issue, respectively; note that the Advocate’s readership is some eighty percent male). Thus in speaking of mainstream advertising’s discovery of the GLBT market, the proviso should be added that this has largely been restricted to gay men, and upscale gay men at that. This is for largely economic reasons, since gay men in general have more disposable income than women. However, there’s some evidence that this difference has been exaggerated, and advertisers may yet discover gay women as an untapped market. The market for both men and women is still a very new one for mainstream advertisers, and things can be expected to continue to evolve over the next five years and for the foreseeable future.

Finally, it should be noted that each issue of OUT magazine, which appeals largely to men, accounted for about one-fourth of the total advertising page count, while Curve, the largest-circulation magazine for lesbians, accounted for less than five percent (at 64 versus twelve pages per issue, respectively; note that the Advocate’s readership is some eighty percent male). Thus in speaking of mainstream advertising’s discovery of the GLBT market, the proviso should be added that this has largely been restricted to gay men, and upscale gay men at that. This is for largely economic reasons, since gay men in general have more disposable income than women. However, there’s some evidence that this difference has been exaggerated, and advertisers may yet discover gay women as an untapped market. The market for both men and women is still a very new one for mainstream advertisers, and things can be expected to continue to evolve over the next five years and for the foreseeable future.

Howard Buford is the founder and CEO of Prime Access, Inc.