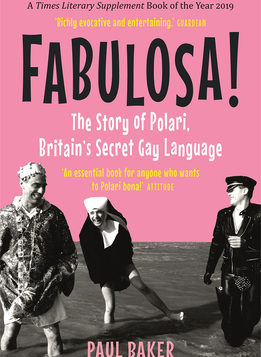

Fabulosa! The Story of Polari, Britain’s Secret Gay Language

Fabulosa! The Story of Polari, Britain’s Secret Gay Language

by Paul Baker

Reaktion Books. 320 pages, $27.50

“SO BONA TO VADA. Oh you/ Your lovely eek and/ Your lovely riah,” sang Morrissey in “Piccadilly Palare” from his 1990 album Bona Drag. “The Piccadilly Palare/ Was just silly slang/ Between me and the boys in my gang,” he reminisces about “Dilly boys” (swishy youth who engage in cruising and prostitution). “On the rack I was/ Easy meat, and a reasonably good buy.”

Morrissey was reviving a nearly extinct argot: Palare, Parlyaree, or Polari. The line translates to, “So good to see you, your lovely face, and lovely hair.” Morrissey’s lyrics condense many cultural and linguistic characteristics of Polari. It borrowed from Italian and French (“bona” from buono or bonne, “vada” from vedere) and Cockney Rhyming Slang or Backslang (“riah” inverts “hair”; “eek” is shortened from “ecaf,” face). By the 20th century, Polari had evolved from a secret language of the homosexual, the molly, and the criminal underworld in England.

Paul Baker, a linguistics professor at Lancaster University, has made it the focus of two decades of study and promotion. Fabulosa! presents an engaging version of his dissertation (published as Polari: The Lost Language of Gay Men in 2002). He easily shifts between the complex linguistic genealogy of Polari and its gay cultural history, focusing particularly on the vicissitudes of its usage in the past half century and tracking this usage with gay politics. Polari enjoyed its heyday in 1960s England thanks to a recurring, campy skit on a BBC radio show. It then almost faded away after the decriminalization of homosexuality in the U.K. in 1967. Baker is bemused and delighted that it has seen a resurgence in this millennium, although perhaps for politically compromised reasons.

Baker’s history of Polari begins with cant or “Peddler’s French,” which in turn has some roots in an Elizabethan “paltry speech” of vagabonds and criminals. Some Cant words, such as “booze,” have persisted in mainstream language. Curiously enough, many Cant words only recently entered Polari thanks to a revival of its usage by the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence (more on that later). There is some evidence that Polari’s gay lexicon was enriched by 18th-century mollies: effeminate and cross-dressing homosexuals who frequented molly houses. These taverns for drunkenness, sex, and prostitution have been wonderfully documented by recent gay historians thanks to detailed police and court records from 18th-century England. Not surprisingly, mollies had many slang words for body parts and sexual acts, though perhaps the most delightful molly phrase was “Where have you been, you saucy queen?” We can thank them for the endless flavors of “queens” that we have today.

Polari’s lexicon was enriched in the 19th century by a variety of immigrants and itinerants: prostitutes, music hall dancers, circus performers, and food peddlers. “Parlyaree” or “parlare” (with its own complex history) contributed to Polari’s counting words, which are clearly Italianate, for example: Una, dooey, tray, and medza (half). The gay thread from Parlyaree to Polari may have been the coded language of performers, dancers, and sex workers (the Piccadilly boys). The gay link is certainly clear when it comes to sailors’ use of Polari and its utility in picking up “sea queens.” Polari’s history also has class elements, with contributions from Cockney and Yiddish, and—in the 20th century—words from military slang and drug culture, such as: “plates” for feet (from Cockney, plates of meat); “meshigener” for crazy; “doobs” for marijuana doobies; and “seafood” for sexually available sailors. All of these subcultures of London undoubtedly had intercourse with the gays on the streets or under the sheets.

Postwar England was particularly hostile to homosexuals (as was the U.S.). Baker argues that this repressive context stimulated the popularity of Polari and its strong association with the gay world. It was the gay insider’s slang for ogling men or probing if a gent at the park was available. Drag queens seem to have regularly “parlareed” Polari in their saucy routines, like Lee Sutton singing: “Bona eke/ Your bon polari almost makes me spring a leak.” The peak of its currency came with Polari’s weekly use on a popular BBC radio comedy show, Round the Horne, which aired from 1966 to 1968. Toward the end of its series of short sketches was a conversation between a pair of flamboyant men, Julian and Sandy (actors Hugh Paddick and Kenneth Williams) and “straight man” Kenneth Horne. The couple regularly peppered their routine with Polari phrases, to the hearty laughter of the audience and their own shrieks of glee. Although Baker describes Julian and Sandy as “a pair of heavily coded gay friends,” they were about as “coded” as Paul Lynde on Hollywood Squares. One has to listen to clips of the show (on YouTube) to appreciate the actual cadence of Polari and the fact that Julian and Sandy were so flaming they must have melted British radios.

Baker explores the risqué Polari and double entendres that the comedians used to evade the censors while cackling about gay sex. Baker’s older Polari-speaking informants all note the importance of the radio show in their development as gay men. Especially for young gay men growing up in a conservative time and in rural areas, it was a huge relief to know they were not alone. To get a real appreciation for Polari as used by gay men of the ’60s, you should watch a BBC4 documentary from 2004 (also available on YouTube). Drag queens and older gay men reminisce about Julian and Sandy and the fun times they had in the repressive old days in pubs. One can imagine them “dishing the dirt,” boasting about “cleaning the kitchen” (anilingus) with a “chicken” last night, or bemoaning “Betty Bracelets” arresting a friend for a “nosh” in a “brandy latch” (toilet stall). The queer irony is that Polari could be a “secret” gay language while being used regularly on a BBC radio show by flaming “pooftahs.” Baker does not specifically solve this conundrum, but can anyone explain how Liberace’s fans and a British court could be convinced he was straight?

After Stonewall and the decriminalization of homosexual acts in Britain, Polari seems to have fallen into disuse. Worse, it was criticized by some as being a language of the closet and of stereotypical queens who sullied the respectable image that gay rights activists were trying to create in the post-AIDS era. Coinciding with that disease marker was a generational divide: Polari was a language of old homosexuals (“antiques” in Polari).

The revival of Polari began in the 1990s thanks to its use by the British Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence in their camp ceremonies, such as their Canterbury Coven’s canonization of Derek Jarman in 1991. They vastly expanded the lexicon of Polari with the production of a Polari translation of the King James Bible, thanks to a group of “research nuns based at the Polari Research Endeavour (PRE) at the City University Manchester (CUM)” (www.polaribible.org). Started in 2003, the 7th edition of the Polari Bible (2013) is available online. It opens with: “In the beginning Gloria created the heaven and the earth. And the earth was nanti form, and void; and munge was upon the eke of the deep. And the Fairy of Gloria trolled upon the eke of aquas.” Like the group itself, the Sisters’ resurrection of Polari is simultaneously campy and politically radical: “Vulgarising [the Bible]by translating it into Polari would be an act of cultural vandalism akin to translation into Scots. But good taste has never yet limited the Sisters’ activities, so we did it anyway.” They hint at a “forthcoming Polari Koran and The Book of Common Screech.” It is just one manifestation of the 1990’s queer politics and academics with their revalorization of camp and gender subversiveness in opposition to the politics of integration and respectability. A variety of artists from Morrissey to edgy drag performers drew on Polari for historical depth and the political inspiration of pre-Stonewall generations of resilient gay men.

Baker highlights another stimulus for the revival of Polari in the 21st century: commodification. Polari words have been emblazoned on T-shirts, bars, and cafés as a retro-chic way of marketing a newly cool lifestyle. The contrasting uses reflect the divergent politics of contemporary LGBT culture that led to the splitting of New York’s 50th anniversary of Stonewall into two celebrations: one political and progressive, the other highly commercialized. Baker, however, avoids political sermonizing and instead closes his appreciation of Polari with an expression of gratitude toward past speakers and his recent informants. Endearingly, Baker integrates self-deprecating confessions of his own development from a shy, working-class gay boy with limited prospects to a still shy but extremely prolific professor. He closes the book by acknowledging how the bravery and bravado of Polari-speaking queens have coaxed him out of his shell to be a “fantabulosa” academic. One thing a drag queen will teach you: you have to be fierce to survive. “You better work it, girl!”

Vernon Rosario is a historian of science and child psychiatrist with the Los Angeles County Department of Mental Health and associate clinical professor of psychiatry at UCLA.