THE ERA extending from the last decade of the 19th century into the 1920’s was a critical one for the reconfiguration of sexual identities in Europe and North America. Picture postcards, a genre whose “golden age” roughly coincided with this period, document this shift in a most vivid and persuasive way.

The early women’s emancipation movement and the First World War both presented enormous challenges to the way people thought about gender roles. Many participants in the women’s suffrage movement struggled not only for the right to vote but also for social, economic, and sexual equality with men. During World War I, countless women left home to take on many of the jobs ordinarily assigned to men, and in doing so experienced a new sense of freedom and empowerment. The movement of women from the domestic sphere to the public sphere so long dominated by men was perceived by many as a threat to the family and to the existing social order.

Meanwhile, in this era of Sigmund Freud and Havelock Ellis, among others, new psychological and medical concepts, such as the libido, bisexuality, and sublimation, were entering into public awareness. Homosexuality was now associated with a distinct type of person rather than just a type of sexual behavior. The stereotypically effeminate “invert” still predominated, but some postcards appeared that hinted at mutual affection, as well as sexual desire, between a same-sex couple.

At the same time, Western travelers to the Middle East and North Africa were discovering cultures in which sexual expression seemed more relaxed and sex roles more fluid than at home. Orientalist notions of the “sensual East” fueled the imaginations of both men and women, further challenging the rigid binary divisions of male/female and masculine/feminine that had rarely if ever been questioned.

In our age of electronic communications, it is hard for us to imagine the role that postcards once played in the lives of everyday people. Postcards were used for ordinary communication, for political propaganda, for courting, as souvenirs for travelers, for advertising products and services and, when converted from photographs, as family mementos. They were produced to celebrate, commemorate, and document a myriad of events, such as devastating earthquakes or floods, battle scenes, and world’s fairs. During the golden age of postcards, billions of cards were printed, collected in albums, and exchanged. In 1909 alone, an estimated 833 million cards were mailed in Great Britain, 668 million in the United States, 160 million in Germany, and 18 million in France. Postcard images celebrated social progress and also reflected social anxieties, such as those aroused by the early feminist movement. Above all, they carried new ideas and trends to countless millions of otherwise isolated individuals.

This article focuses on commercially produced postcards that were printed in large numbers and circulated widely throughout the world. Real photo postcards, in contrast, whether produced by professional or amateur photographers, also provide valuable insights into social history but were most often printed in limited numbers, and their images can be difficult if not impossible to identify. (Who is being photographed, by whom, where, when and why?) The postcards reproduced here are from my personal collection, and my hope is that they will offer a flavor of the shifting sex and gender ideas of this era.

Role Reversals

It was popularly believed in the 19th and early 20th centuries that women and men were radically different by design, and that nature had prepared each for specific roles in society. Any crossing of these boundaries was thought to do harm both to the individual and to the society at large. In 1873, for example, Dr. Edward Clarke of Harvard argued that women who chose to attend schools of higher education risked damaging their health and could face a life of hysteria, uterine diseases, and derangements of the nervous system. Similarly, opponents of women attending college argued as late as 1900 that higher education might cause women to lose their instinct for giving birth and risked the creation of puny, enfeebled children. By the 1920’s, however, the traditional gender dichotomy was becoming a bit more blurred, and homosexuality was increasingly accepted by the intellectual avant-garde. Changes are most evident in fashion, where it was not uncommon, both in Europe and the U.S., to find women with short hair, dressed in men’s attire, and smoking in public.

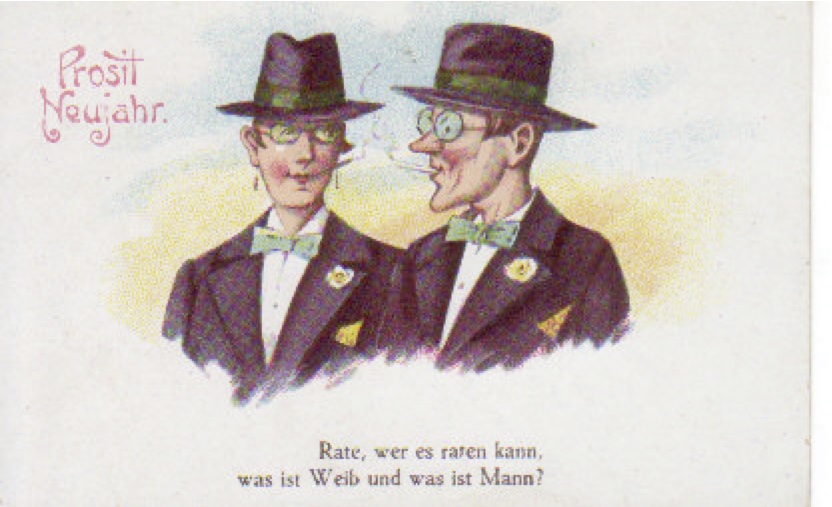

Fig. 1. In 1909, a set of twelve anti-suffragist postcards was produced by the Dunston-Weiler Lithograph Company of New York. Its intent was to  satirize the movement for women’s rights. In Uncle Sam, Suffragee, America’s most popular symbol is seen dressed in drag. He is depicted as clean shaven, without his traditional beard, and wearing a skirt and a woman’s bonnet instead of the expected trousers, tail, and top hat. The term “suffragee” places him as the passive object of the suffragist movement, depriving him of the power ordinarily associated with this icon of American strength and nationhood. The message: the suffragist movement is responsible for the feminization of America itself.

satirize the movement for women’s rights. In Uncle Sam, Suffragee, America’s most popular symbol is seen dressed in drag. He is depicted as clean shaven, without his traditional beard, and wearing a skirt and a woman’s bonnet instead of the expected trousers, tail, and top hat. The term “suffragee” places him as the passive object of the suffragist movement, depriving him of the power ordinarily associated with this icon of American strength and nationhood. The message: the suffragist movement is responsible for the feminization of America itself.

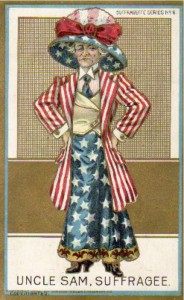

Fig. 2. An early German postcard dated 1901 lampoons the consequences that can be expected from women’s equality. Titled “Modern Marriage,” the caption below reads: “She is wearing the pants.” The male in the picture is a sad figure, reduced to playing the traditional female role of nurturing an infant. He stands in a frilly woman’s dress that looks especially ridiculous given his full mustache. By his side, his threatening wife, dressed in undergarments and pants, stands menacingly with a shoe in her hand.

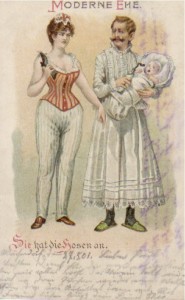

Fig. 3. Two figures, similarly dressed in men’s outfits, appear on this German New Year’s card. The caption below reads: “Tell me, if tell me you can, which is the wife and which is the husband?” The struggle for women’s rights has reached the point  when one can no longer distinguish the male from the female. Though its intent is humorous, the card reflects the anxiety caused by the perception that gender roles were breaking down. Androgyny in Germany between the wars came to symbolize modernity, as did homosexuality, which most people still saw as an unnatural masculinization of women and a feminization of men, and all that that implied for the future of the family.

when one can no longer distinguish the male from the female. Though its intent is humorous, the card reflects the anxiety caused by the perception that gender roles were breaking down. Androgyny in Germany between the wars came to symbolize modernity, as did homosexuality, which most people still saw as an unnatural masculinization of women and a feminization of men, and all that that implied for the future of the family.

The Pansy

The prevailing assumption during this era was that homosexual men were effeminate, while lesbians were unnaturally masculine. While heterosexual males might have sexual encounters with “pansies,” so long as they played the active, insertive role in sex, their heterosexuality was not in question. On early postcards, it is unusual to find images of the pervert, which is not surprising given he was regarded in most Western countries as a willful sinner, a psychological or medical specimen to be pitied, or a predatory criminal. References in wartime propaganda, however, provide an exception.

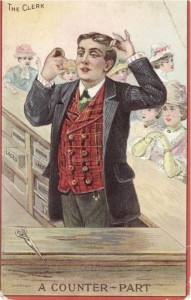

Fig. 4. This characterization of a male store clerk as an effeminate pretty boy can be traced as far back as 1860, to a parody of Walt Whitman’s  “Song of Myself.” It begins: “I am the Counter-jumper, weak and effeminate./ I love to loaf and lie about dry-goods.” In the illustration, captioned “The Clerk: A Counter-Part,” such a clerk primps before a mirror, oblivious to the many women customers needing to be helped. One woman is raising her finger to get his attention, another looks on in dismay, while a third has decided to leave. As the lad tries to part his hair, his delicate features and uplifted fingers convey loud and clear the image of effeminacy.

“Song of Myself.” It begins: “I am the Counter-jumper, weak and effeminate./ I love to loaf and lie about dry-goods.” In the illustration, captioned “The Clerk: A Counter-Part,” such a clerk primps before a mirror, oblivious to the many women customers needing to be helped. One woman is raising her finger to get his attention, another looks on in dismay, while a third has decided to leave. As the lad tries to part his hair, his delicate features and uplifted fingers convey loud and clear the image of effeminacy.

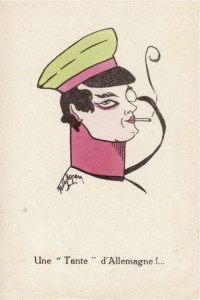

Fig. 5. This postcard is of Belgian origin and dates from the First World War. It uses the French term “tante,” meaning “aunt,” or in this case “auntie,” to label a dandified German military officer. Not only is the figure depicted as effete, what with his weak chin, reddened lips and eyes, and monocle, but the caption makes clear by its gender reversal that the subject is homosexual.

Fig. 5. This postcard is of Belgian origin and dates from the First World War. It uses the French term “tante,” meaning “aunt,” or in this case “auntie,” to label a dandified German military officer. Not only is the figure depicted as effete, what with his weak chin, reddened lips and eyes, and monocle, but the caption makes clear by its gender reversal that the subject is homosexual.

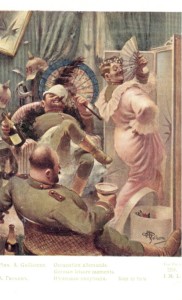

Fig. 6. On this French postcard, German soldiers, their helmets set aside, are drinking and enjoying a drag act by one of their fellow officers. The caption below, “Germans occupying themselves,” is in French, English, and Russian (the languages of the Allies), while on the verso, “The European War of 1914-1915. Patriotic Edition” appears in French. The entertainer is shown as effeminate, wearing a pink dress over his uniform. Another officer is reclining with an open parasol, while a tilted picture on the wall hints to the debauchery taking place. A second interpretation of the French caption, “Occupation allemande,” is “German [military]occupation,” suggesting that such orgies are the norm in German-occupied lands.

Fig. 6. On this French postcard, German soldiers, their helmets set aside, are drinking and enjoying a drag act by one of their fellow officers. The caption below, “Germans occupying themselves,” is in French, English, and Russian (the languages of the Allies), while on the verso, “The European War of 1914-1915. Patriotic Edition” appears in French. The entertainer is shown as effeminate, wearing a pink dress over his uniform. Another officer is reclining with an open parasol, while a tilted picture on the wall hints to the debauchery taking place. A second interpretation of the French caption, “Occupation allemande,” is “German [military]occupation,” suggesting that such orgies are the norm in German-occupied lands.

Mutual Attractions

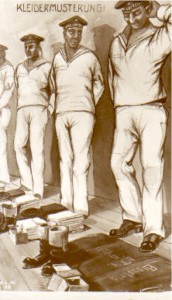

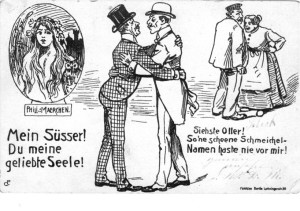

Images showing mutual same-sex attraction between men are rare. Both of the following German cards depict their subjects with humor, even sympathy. In the first, the image of the male sailor, long an icon of virility and object of female desire, takes on a new twist. In the second, a married woman extols the openly expressed affections of a same-sex couple. Significantly, both cards reflect a positive acknowledgment of emerging sexual identities: men being attracted to one another as a consequence of a shared sexual orientation.

Fig. 7. Two sailors in a line waiting for clothing inspection appear to be breaking rank. The one on the far right assumes a pose of modesty, his eyes cast downward and his left arm held coyly behind his head. The next sailor in line glances over with obvious desire. The undated German postcard is titled “Clothing Inspection.”

Fig. 7. Two sailors in a line waiting for clothing inspection appear to be breaking rank. The one on the far right assumes a pose of modesty, his eyes cast downward and his left arm held coyly behind his head. The next sailor in line glances over with obvious desire. The undated German postcard is titled “Clothing Inspection.”

Fig. 8. In the card’s center, two men in male attire embrace one another. The man on the left appears a bit foppish with his checkered  suit, and he appears somewhat effeminate with his hindquarters protruding. The two men seem to be about the same age and class background. One cries out “My Sweetie!” while the other responds “My Beloved Soul!” To the right, a woman chides her husband (who looks back on the male couple with resentment): “Hey, old guy, you never flatter me with such pretty names!”

suit, and he appears somewhat effeminate with his hindquarters protruding. The two men seem to be about the same age and class background. One cries out “My Sweetie!” while the other responds “My Beloved Soul!” To the right, a woman chides her husband (who looks back on the male couple with resentment): “Hey, old guy, you never flatter me with such pretty names!”

Cross-Dressing

Cross-dressing has appeared throughout all of human history, and the motivations for it are varied. It has played an important role in religious ritual and theatre and, in more recent times, as a protest against social norms. Within the military, where women have been known to disguise themselves as men in order to serve, same-sex theatre troupes routinely featured men playing female roles until the 1940’s. More directly associated with gay culture, drag performance has been a mainstay in challenging society’s traditional sex and gender dichotomies.

Fig. 9. In this illustration, a German female officer in uniform and helmet is being admired by an elegantly clad woman in a dress and tight stockings. The juxtaposition of masculine and feminine in the figures could hardly be more pronounced. Women in the early 20th century held no such positions of power in the German army, but fantasies of females cross-dressing as soldiers were not uncommon, judging by the abundance of cards similar to this one.

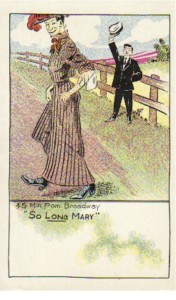

Fig. 10. This rather curious card makes reference to the song, “So Long Mary,” from George M. Cohan’s musical Forty-Five Minutes From  Broadway, which opened at the New Amsterdam Theater in New York City on January 1, 1906. On the card, Mary has been transformed into a man in drag with hairy arms. The name “Mary” is also homosexual slang, originating in the 19th century and used to denote an effeminate man.

Broadway, which opened at the New Amsterdam Theater in New York City on January 1, 1906. On the card, Mary has been transformed into a man in drag with hairy arms. The name “Mary” is also homosexual slang, originating in the 19th century and used to denote an effeminate man.

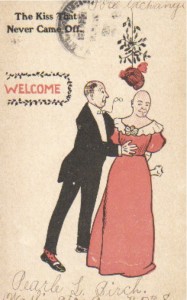

Fig. 11. On an American card postmarked 1906, “The Kiss That Never Came Off,” a gentleman in formal attire expresses his shock as he is about to deliver a kiss to his date. A hanging vine ornament has snagged the creature’s wig, and the “she” has suddenly become a “he”!

The Lure of the East

Already in the 19th century, with a rise in travel, wealthy Europeans were discovering the “exotic Orient.” Painters and writers flocked to such countries as Turkey, Algeria, Tunisia, Syria, and Palestine, where they were inspired by the picturesque landscapes, magnificent architecture, and strange ways of life they found. Travel writers’ tendency to exoticize and romanticize the East contributed to the rise of what came to be called “orientalism.” Among other discoveries, they found sex roles to be more fluid than those of European societies. Pictures of life in the Orient became a mainstay of fantasy, symbolizing for both men and women a freedom from the rigid gender and sexual barriers of Christendom.

Many gay men at the turn of the last century, including writers André Gide, Oscar Wilde, and E. M. Forster, and photographer Wilhelm von Gloeden, found in North Africa an opportunity to experience same-sex love in a surprisingly tolerant environment. Travel journals and memoirs tell of their liaisons with Arab adolescents and the feeling of breaking away from Europe’s suffocating strictures and hypocritical sexual mores. European women, some unaccompanied, also traveled to the Middle East and North Africa in this period, and they wrote of new freedoms and self-discoveries unimaginable back home. A small number married native men and decided not to return home.

Fig. 12. This early postcard from Egypt is titled “Egypt – Haywal” with a caption in French that translates as “An eccentric male dancer dressed as a  female dancer.” A Haywal (or Khawal) was an effeminate male dancer known for his acrobatic flexibility and sexually alluring movements, who often performed in public in 19th- and early 20th-century Egypt. The term Haywal later became a derogatory term in Arabic. In his 1836 book An Account of the Manners and Customs of the Modern Egyptian, author Edward William Lane describes Khawals as dancing accompanied by the sound of castanets, with hair grown long and braided in the manner of women, dressed in a tight vest, a girdle, and a kind of petticoat. All of these features can be seen in the Khawal pictured. The public acceptance of such dancers testifies to a degree of openness to gender nonconformity that was absent in European societies.

female dancer.” A Haywal (or Khawal) was an effeminate male dancer known for his acrobatic flexibility and sexually alluring movements, who often performed in public in 19th- and early 20th-century Egypt. The term Haywal later became a derogatory term in Arabic. In his 1836 book An Account of the Manners and Customs of the Modern Egyptian, author Edward William Lane describes Khawals as dancing accompanied by the sound of castanets, with hair grown long and braided in the manner of women, dressed in a tight vest, a girdle, and a kind of petticoat. All of these features can be seen in the Khawal pictured. The public acceptance of such dancers testifies to a degree of openness to gender nonconformity that was absent in European societies.

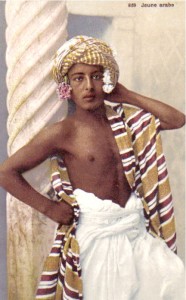

Fig. 13. The androgynous male pictured here is a youth from northern Africa. He stands in a typically feminine pose with his left arm raised to highlight his chest, while his upper torso is partially revealed by the careful undraping of his garment. Flowers frame his face as he looks enticingly toward the viewer. The team of Austrian and Swiss photographers, Lehnert and Land-rock, produced this and many other cards capitalizing on European stereotypes of  northern Africans. The card’s French caption translates as “Young Arab.” It was common for Europeans to label their colonial subjects with generic categories, such as “Negro Type,” depriving them of an individual identity.

northern Africans. The card’s French caption translates as “Young Arab.” It was common for Europeans to label their colonial subjects with generic categories, such as “Negro Type,” depriving them of an individual identity.

Fig. 14. One of the most popular images to be found on colonial era postcards is that of “native” woman. These women, most often shown as dancers, bare-breasted or in harem settings, aroused the interest of white Europeans for their sheer erotic appeal. This photographer shows two bare-breasted females in a suggestive pose and a setting that evokes a harem and all the legendary sensuality that that implies. In actuality, male outsiders were rarely allowed into the women’s quarters of Muslim homes, and many of the scenes of harem life with women in evocative poses were created with non-Muslim women or hired prostitutes as stand-ins and posed in the photographer’s studio. This card’s caption reads “Women of the South at Home.” Such pictures with their lesbian undertones undoubtedly captured the imaginations of same-sex loving women in Europe.

in harem settings, aroused the interest of white Europeans for their sheer erotic appeal. This photographer shows two bare-breasted females in a suggestive pose and a setting that evokes a harem and all the legendary sensuality that that implies. In actuality, male outsiders were rarely allowed into the women’s quarters of Muslim homes, and many of the scenes of harem life with women in evocative poses were created with non-Muslim women or hired prostitutes as stand-ins and posed in the photographer’s studio. This card’s caption reads “Women of the South at Home.” Such pictures with their lesbian undertones undoubtedly captured the imaginations of same-sex loving women in Europe.

Stephan Likosky, a freelance writer living in New York, is editor of Coming Out: An Anthology of International Gay and Lesbian Writings (1992).