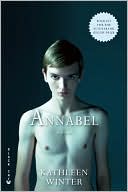

Annabel

Annabel

by Kathleen Winter

Grove Press, Black Cat. 480 pages, $14.95 (paper)

ON THE MORNING that Wayne Blake entered the world, the midwife, Thomasina Baikie, did what came naturally: she checked to see if the baby was male or female, and was shocked to discover that the baby appeared to be both. After tending to the mother, Jacinta, Thomasina broke the news to the new father.

Treadway Blake, like his father and his father’s father, was a trapper in his native Labrador. Spending six months outdoors was something he could live with; a child like Wayne was not. When Thomasina told Treadway that his son was also his daughter, Treadway decreed that, no, Wayne was a boy. Jacinta, broken-hearted and already loving the girl inside her son, reluctantly agreed with her husband.

Wayne is never told of his anomalous nature. Thomasina, grieving for her own lost family, leaves Labrador. Jacinta takes her child to see doctors, who agree to define Wayne as a boy. Treadway finally has his son, but not the son he wanted. Growing up, Wayne prefers the company of girls, especially that of Wallace Michelin or “Wally.” This friendship is happy and easygoing because Wally never notices that Wayne isn’t like other the boys. But then Wayne’s body does something medically unusual, to say the least: Wayne spontaneously becomes pregnant with his own baby. While Treadway holds fast to his idea of having a son, for Wayne the time has come to learn a truth about himself that will explain so much, even while raising a whole new set of questions.

Confused and ashamed, Wayne knows he can never speak of his secret to anyone in Labrador. He can’t talk to his parents about it, and he could never tell Wally, who drifted away from him years ago. Then Wayne himself begins to drift. Wandering, he leaves his home in Labrador and moves to St. John, where he finds a job and a friend who it turns out can’t be trusted. Saddest of all, Wayne realizes that he can never be the son his father wanted.

Annabel, told in third person, is nuanced, heartbreaking, and poetic. It pulses with an ethereal sense of a lost time as it takes us back forty years into a remote town in Canada. Kathleen Winter writes with a certain twinkle in her eye, exhibiting a wry sense of humor that sometimes erupts in the most surprising places. That can catch a reader off-guard, daring us to laugh in the midst of a family tragedy as dark secrets, desires, and dreams are revealed.

The main characters in the novel are for the most part likable people. Wayne is an introspective kid, almost a little boring in his cluelessness. Thomasina is a woman ahead of her time. Treadway, though a product of his generation, tries hard to love what he can’t help thinking is a flawed son, while his wife slowly descends into a depression borne of everyone else’s unhappiness.

What may be frustrating to some, though, are the plotlines left wide-open: as much as she loved him, for instance, why is Thomasina such an on-again, off-again adult in Wayne’s life? And is Wayne really so dense and unself-conscious that he doesn’t discover his own secret until his pre-teen years? While some have compared this novel to Jeffrey Eugenides’ Middlesex (2002)—and though there are certain resemblances—this novel is clearly less “literary,” which could make it more accessible for some readers, less challenging for others.

________________________________________________________

Terri Schlichenmeyer is a freelance writer based in Wisconsin.