WHEN THE BODY of Rep. John Randolph of Virginia was exhumed, they discovered that the roots of a nearby pine tree had pierced his coffin, threaded themselves through his long flowing hair, penetrated his eye sockets and, feeding off his brain, had filled his skull with their white, spidery tendrils. It was a macabre but appropriately sensational discovery for a body that had been the topic of so much gossip and speculation while the man was alive.

Known as John Randolph of Roanoke (appending the name of one of his estates in order to distinguish himself from other relatives of the same name), Randolph was a member of Congress and a fixture in the nation’s capital during the Jefferson and Madison administrations. Randolph was born in 1773 on a plantation named Matoax and later inherited Roanoke, but he spent most of his youth and a good part of his manhood on a third family plantation, aptly named Bizarre, in a family that can best be described as Southern Gothic. Young Jack was a sensitive and high-strung child. When thwarted, he would work himself into tantrums so violent they caused him to pass out. His father died when he was only two, but he enjoyed an idyllic childhood of comfort and privilege under the care of a doting mother—until she remarried and his stepfather felt compelled to beat the sissy out of the effeminate boy. The first corporal punishment Randolph ever received was inflicted “as soon as the festivities of the wedding had ceased,” he later wrote, and ushered in a regime of “most intolerable tyranny.”

for Russia onboard ship Concord.

Harsh discipline left Randolph with a burning resentment against tyranny of all kinds, but also with a craving for strong masculine authority figures he could emulate, a complex desire that later erupted in unexpected ways. When in Congress arguing against the establishment of a national bank, Randolph rejected the imposition of “a master with a quill behind his ear”—a mere bookkeeper or accountant who might direct the nation’s fate. “If I must have a master,” he proclaimed, “let him be one with epaulettes, something that I could fear and respect, something I could look up to.” Later in life, when Andrew Jackson had replaced Thomas Jefferson as his great idol, in an uncharacteristically fawning letter Randolph cast Jackson as Alexander the Great and himself as his lover Hephaestion, though he added: “I trust that I am something better than his minion (the nature of their connection, if I forget it not, was Greek love).”

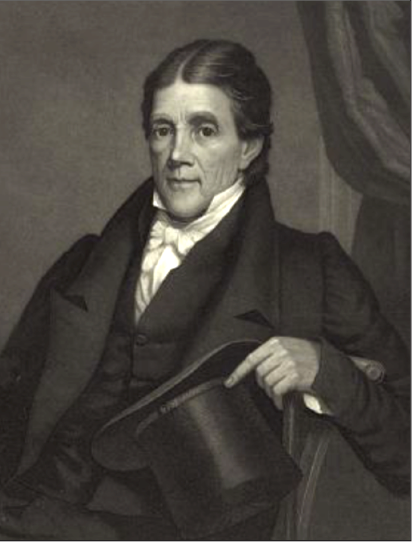

Randolph was first elected to the House in 1798, and because of his sharp intellect and unsurpassed oratorical skills he was immediately assigned the powerful position of chairman of the Ways and Means Committee, serving also as majority whip, and eventually as majority leader. Still, his androgynous appearance bewildered his contemporaries. “His whole organization was delicate as a woman’s; nay more delicate,” one observed. “His long straight hair,” another wrote, “is parted on the top and a portion hangs down on each side, while the rest is carelessly tied up behind and flows down his back. His voice is shrill and effeminate and occasionally broken by low tones which you hear from dwarfs or deformed people.” Another was pointedly dismissive: “As to Mr. John Randolph you can scarcely form an idea of a human figure whose appearance is more contemptible… one would suppose him to be either by nature, or manual operation fixed for an Italian singer, indeed there are strong suspicions of a physical disability.”

At times Randolph was described almost as one of the walking dead. His lips were “the color of indigo” and his complexion was frequently compared to parchment, “destitute of any beard, and as smooth as a woman’s.” One observer described his skin as “precisely that of a mummy; withered, saffron, dry, and bloodless.” Contemporaries were also unsettled by Randolph’s mesmerizing eyes. His pupils were usually dilated into huge black disks under the effect of frequent drunkenness, and, later in life, as he depended more and more on opium to dull his misery, they would contract into tiny black pinpoints set in a field of eerily glowing hazel.

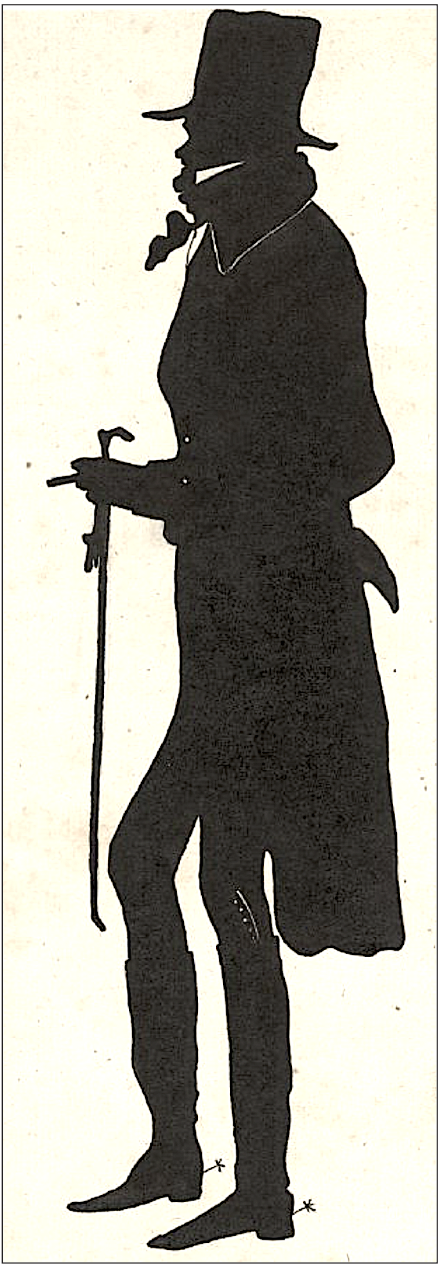

Nor was Randolph’s behavior in Congress what the delegates had come to expect from their colleagues. He would sweep into the chamber wearing knee-high riding boots, leather breeches, and an ankle-length frocked coat that swirled around him like a cape as he sashayed, smacking his riding crop against his gloved palm. Carefully setting aside his hat and whip, he would (“very deliberately and very coolly—provokingly so,” as one contemporary described it) untie the bandana from his throat and wrap it around his head to hold back his long raven hair, and then he would strike a dramatic pose and pause until the Speaker of the House prodded him to get on with it.

This was clearly gender performance, and Randolph was aware that it repulsed some of his colleagues in the House, but he felt that he had little choice. He was unable to present himself as a traditionally masculine figure and did not wish to be a woman, so he enacted a middle sex and mocked his fellows for their brutish manliness. When one representative made a snide comment on the floor of the House about Randolph’s apparent lack of virility, the honorable member from the 7th District of Virginia clapped back: “You pride yourself on your animal faculty, in which the negro is your equal and the jackass your superior.”

A descendent of Pocahontas, Randolph reveled in his mixed-raced ancestry, crediting his Indian blood for the “wildness” in his nature. He felt that it was this untamed Native American spirit alone that allowed him to construct a masculine identity, despite his very feminine appearance. “Indeed I have remarked in myself, from my earliest recollection, a delicacy or effeminacy of complexion, that, but for a spice of the devil in my temper, would have consigned me to the distaff or the needle.”

Like many plantation owners of the period, Randolph inherited a problem he detested but did not have the moral gumption to put right. Matoax, Bizarre, and Roanoke, the three plantations that he inhabited at various times, all depended on the labor of enslaved African Americans, and manumitting his workers would have left Randolph impoverished—and on the same footing as thousands of other white American men who had only grit, talent, and opportunity with which to raise themselves in the world. Randolph excused his continued use of enslaved workers with the specious argument that he needed to operate his plantations at a profit in order to earn enough money to house, clothe, and feed the people he was enslaving. Still, it should be noted that Randolph never bought or sold enslaved people. Throughout his life he referred to himself as an ami des noirs—at a time when his neighbors would have employed a blunter English term—and in his final years his sole intimate companions were his two Black body servants, John and Juba. Upon his death he freed all of his enslaved workers, and as reparations he provided them with land of their own to farm as free persons of color—something Washington, Jefferson, Madison, Monroe, and Hamilton could have done but did not.

Engraving by John Sartain after the original from life by Catlin taken during the sitting of the Virginia State Convention in 1831.”

Randolph was a fervent acolyte of Jefferson—until his fellow Virginian began to waver in his anti-Federalist opposition to a strong central government. In time Randolph’s party (and the nation) moved on and he was left behind, defending a staunchly conservative position that became more and more untenable as the country expanded westward. Feeling he could support neither the Democratic-Republicans nor the Federalists, Randolph formed his own party, which he called the Tertium Quid (the Third Thing)—a curious choice of name for a man who had been denigrated throughout his life for not being convincingly male or female.

Randolph was elected to the House of Representatives seven times, served two years in the Senate, and was briefly the U.S. ambassador to Russia, but as he aged his political conservatism calcified into a curmudgeonly opposition to anything that vaguely smacked of progress. He was wracked with physical ailments and was invariably drunk or drugged. His associates in Congress looked upon him with pity and regret, but never ceased to be impressed by his dazzling erudition, nor to fear his caustic tongue. “At times he is the most entertaining and amusing man alive,” wrote a congressman from Massachusetts, “with manners most pleasant and agreeable; and at other times he is sour, morose, crabbed, ill-natured, and sarcastic, rude in manners, and repulsive to everybody. Indeed, I think he is partially deranged, and seldom in the full possession of his reason.” Perhaps the saddest description of Randolph came from a contemporary who witnessed the bitter, grotesque creature he had evolved into: “a flowing gargoyle of vituperation.”

When John Randolph died, Dr. Francis West conducted a postmortem examination and reported that the “scrotum was scarcely at all developed” and that he possessed only a right testicle, which was “the size of a small bean.” West was severely criticized for releasing the results of the autopsy, and thereafter declined to give more details. A recent biographer argues convincingly that Randolph was born with Klinefelter Syndrome, a condition in which an individual possesses one Y and two X chromosomes, inhibiting him from developing secondary male characteristics.

In 2020 a cisgender, straight-acting, openly gay man was appointed to the President’s cabinet, and the nation applauded or grumbled. But it is worth noting that in the early years of the Republic (before the Victorian straitjackets of gender were strapped into place), a non-binary politician who self-identified as mixed-race became one of the most powerful men in Washington. Throughout his years in Congress, Randolph alternated between highly skillful behind-the-scenes maneuvering to press his party’s legislative agenda, and an intentionally provocative brandishing of his effeminacy. He astonished with his intellect, intimidated with his sharp tongue, and entertained an entire nation of newspaper readers with his undeniable star quality. Whatever the cause of his gender ambiguity, Randolph used his eccentricities of dress and behavior to lean into what could have been an insurmountable handicap for any politician. When the gentleman from Virginia swept onto the floor of Congress (his high-heel boots clicking, his frocked coat twirling around him), slapped down his whip, whisked off his bandana to tie back his long, flowing hair, and then proceeded to savage his foes in the piping falsetto of a prepubescent boy, John Randolph of Roanoke was proclaiming himself to be his own special creation.

References

Dawidoff, Robert. The Education of John Randolph. W.W. Norton & Co., 1979.

Johnson, David. John Randolph of Roanoke (Southern Biography Series). LSU Press, 2012.

Kierner, Cynthia A. Scandal at Bizarre: Rumor and Reputation in Jefferson’s America. Palgrave Macmillan, 2004.

William Benemann is the author of Unruly Desires: American Sailors and Homosexualities in the Age of Sail and Men in Eden: William Drummond Stewart and Same-Sex Desire in the Rocky Mountain Fur Trade.

Discussion1 Comment

Kudos to William Benemann for his excellent profile of John Randolph of Roanoke, a true original and bona fide Southern eccentric. Randolph is the antagonist in my new historical novel, Defamed, about his cousin Nancy, arguably the most scandalous woman in Jeffersonian America. Nancy was relentlessly and unfairly tormented by John until she gained the power to beat him at his own game in a take-no-prisoners war of words that lasted for decades. Randolph was, by turns, vicious and acerbic, generous and compassionate, and his self-destruction was perhaps inevitable. As I wrote in Defamed, “Coupled with the premature deaths of his two brothers and one of their sons, and the madness of another son, one might conclude that this branch of the Randolph family was withered by inbreeding.” Crazy or not, there is no denying Randolph’s rapier-sharp wit. He called Martin Van Buren “such a monster of stealth and duplicity, I accused him of rowing with muffled oars.” He dissed Senator Benjamin Hardin as “an enthusiastic but roughhewn Kentuckian who sounds like a carving knife whetted on a brickbat.” He aimed his wittiest barb at Secretary of State Edward Livingston, “a man of splendid abilities but utterly corrupt. He stinks and shines like rotten mackerel by moonlight.” Randolph’s sexual preference, if indeed he had any, remain debatable, but there’s no doubt he threw some mighty fine nineteenth-century shade.