ON JAMES BALDWIN

ON JAMES BALDWIN

by Colm Tóibín

Brandeis Univ. Press.

147 pages, $18.95

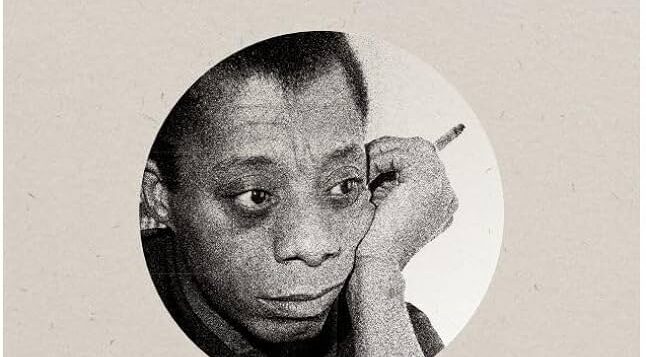

AS JAMES BALDWIN’S 100th birthday passes, I recall the line from Pablo Neruda’s poem “I Ask for Silence”: “I have lived so much that some day they will have to forget me forcibly.” Instead of fading from memory as his work aged, the man Bobby Kennedy called “Martin Luther Queen” has become an unforgettable icon, partly for his writing about the mid-20th-century Black American experience, partly for being a visible gay person, and ultimately for his exceptional abilities as a writer and presenter of important themes.

Renowned gay Irish writer Colm Tóibín has recognized James Baldwin’s entry into the canon of America’s most important writers with a rich, varied collection of five lengthy essays that were originally delivered as the Mandel Lectures at Brandeis University. His view of Baldwin from this distinctive international angle shows that the weight and value of this unique American voice have been widely recognized both within and beyond our borders.

The gay community is quite right to claim Baldwin with pride, as we’d be hard-pressed to find a better symbol for our own stubborn unwillingness to be forgotten. Still, his laser focus on racial justice in his principal works makes him an even larger figure in Black literary history than as a gay writer and activist. (This was also true of other mid-century Black gay men, such as Alain Locke, Bayard Rustin, and Langston Hughes, and perhaps also of lesbians such as Audre Lorde.)

Baldwin’s novel Giovanni’s Room involves a gay relationship in which the male protagonist desires another man but seems incapable of love. Like the first edition of Gore Vidal’s The City and the Pillar, it was criticized by many gay readers because it ended tragically. This issue was not limited to Baldwin, but it was one that he dealt with often. One of his early stories, “The Outing” (1951), involves a group of teenagers on a church trip. Two of the boys are close friends, and one admits to his love for the other. Despite the kind, caring way that they treat each other, it becomes clear that one boy will end up in a traditional straight relationship while the other faces an unknown path where happiness may remain out of reach. The question is left hanging for the reader to contemplate, a practice Baldwin was famous for.

Tóibín, casting about at age eighteen for a mode of thinking different from that of the Irish Catholic culture in which he was raised, landed on Baldwin’s Go Tell It on the Mountain. This novel had aroused the doubts of Ralph Ellison, who said of it that Baldwin “doesn’t know the difference between getting religion and going homo.” But even Ellison granted the brilliance of Baldwin’s depiction of religion as a kind of performance, which Tóibín describes as “soaked in church ritual as spectacle,” something familiar to him as a former altar boy. Tóibín explains: “I came to Baldwin’s novel with experiences and desires of my own that I did not understand. … I did not connect my interest in religious ritual with my own pale, hidden homosexuality.”

Baldwin was a perceptive observer of scenes in other authors’ work—for example, in a story by Richard Wright in which a Black man trained as a cook dresses as a woman in order to get a cook’s job with an upper-crust white family. That Tóibín himself had the breadth of vision to see Baldwin’s life and work from many angles is one of the strengths of this collection. Baldwin was appreciative of Henry James, and Tóibín notes this in several places, including an interesting comparison of moments in James’ The Ambassadors and Baldwin’s Giovanni’s Room.

As if Tóibín’s insights about Baldwin were not enough to make this short collection a keeper, we also get Tóibín riffing on his own experiences as a young gay man arriving on the Continent at a time when gay life was both obvious and tentative. The author’s frustrations in 1975 Barcelona are apparent, and comparisons with Baldwin’s own, at an earlier time in Paris, feel natural and enlightening. Tóibín notes that “homosexuals were plenty, but images of gay life were scarce, where much was fleeting and furtive.”

Outside of literary life, Black gay writers who spoke up were subject to special criticism. Eldridge Cleaver said, referring to Baldwin, that homosexuality was a sickness, in part because Black gay writers “are unable to have a baby by a white man.” But speaking out was part of who Baldwin was and why we revere him today, not just as a writer, but as an American and as a human being.

Alan Contreras is a writer and higher education consultant who lives in Eugene, Oregon.