I WROTE a 600-page novel that was provoked by three words in a throw-away line from Claude Manceron’s majestic history of the French Revolution, the first volume of which describes the Ancien Régime, Twilight of the Old Order, 1774-1778. The three words, on page 545, were: “Villette, urbane homosexual.” The rest of the sentence describes Villette’s father, a banker who made so much money supplying Louis XV’s armies that he was able to purchase for himself and his heirs the title of “marquis.”

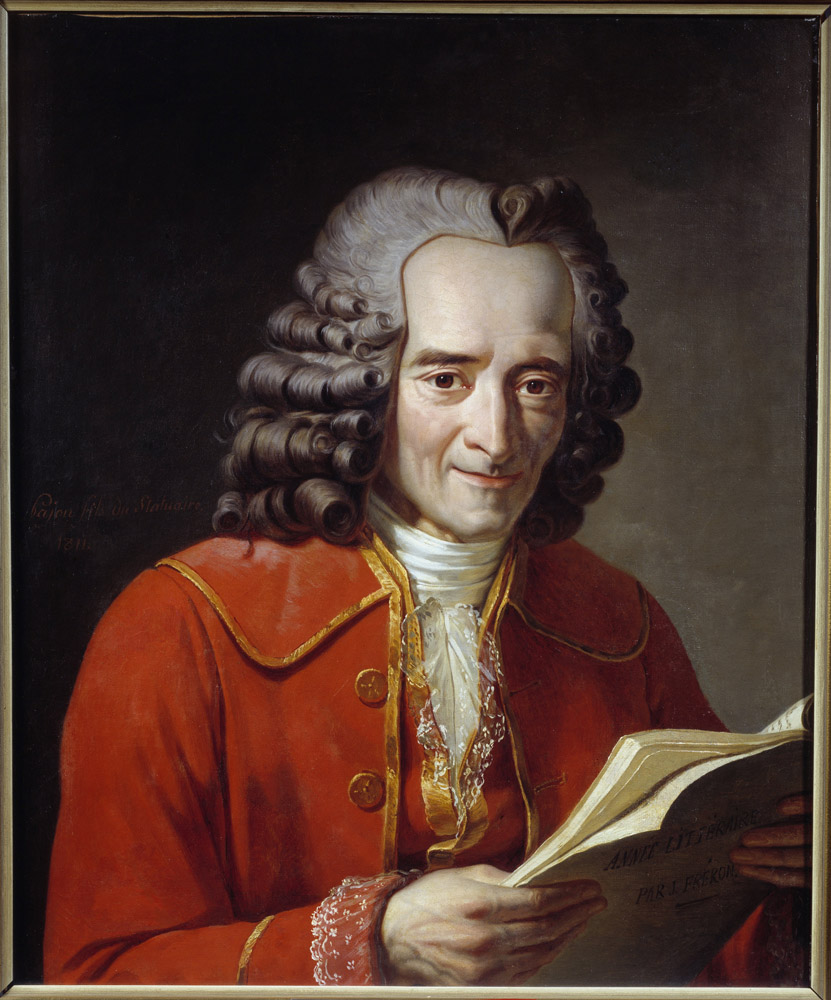

Manceron’s interest in Villette, fils, arose from the historical fact that, as a friend of Voltaire, the Marquis de Villette became the philosopher’s host in Paris when the old man decided in February of 1778 that it was safe to return home. Louis XV had tired of not only his official historiographer’s utter lack of deference to His Royal Magnificence but also his militant irreverence towards the Church and had banned Voltaire from his realm. The return of the prodigal philosopher four years after the death of Louis XV, following an exile of nearly thirty years, fomented passions and disturbances that rippled through Europe. These waves became part of the tsunami of 1789 that brought down not only the monarchy but also an institution that Voltaire despised even more: the Catholic Church of France. But who knew this would happen?

Of course, from Voltaire’s perspective, it was necessary to persevere in his attempts to expose injustice in a society that was run by the immoveable collusion of ecclesiastics and government officials. He would continue to spread his mantra of “Écrasez l’Infâme!” in illicit publications that sold well all over the realm. Everything the Archbishop alleged was true: Voltaire wanted to tear religion down. This is what Voltaire did. This is what he had always done.

What he had not always done, however, was to live at the house of a known “urbane homosexual.” I was surprised and pleased to find this out, of course, but I needed more information. Did Voltaire know that his host in Paris was, to use the word of the time, an “anti-physique”? Was he aware of his host’s predilection for bringing in handsome young boys from the provinces to serve as his valets, postilions, and scullery lackeys? Did he also know that a mutual friend of theirs, the Marquis de Thibouville—a failed fellow dramaturge with whom he had corresponded for decades and who was another well-known anti-physique—was also living under the same roof? And did Voltaire know that Villette and Thibouville were “ensemble”? If he did, then he was flouting religious law to an even greater extent than before. After all, the last sodomites to be burned at the stake had been dispatched quite recently, in 1750. In order to live intimately with these aristocratic fops, Voltaire must also have suspended any personal animosity he may have had for anti-physiques.

I BEGAN my research by going to the hôtel de Villette (hôtel particulier, back then, meant a private residence or aristocratic townhouse), on the Quai Voltaire directly across the Seine from the Louvre. Of course, back in 1778 the dock had a different name, Quai des Théâtins, named for a big church whose shadow fell daily onto this house where Voltaire came to live. Today, planted in front of the building is one of the “Histoire de Paris” information plaques in the shape of an oar that gives more detailed information. As luck would have it, Voltaire had lived so long that he had stayed in this house before, in 1724, when it belonged to the Présidente Bernière, widow of an old friend of his. Since then, the Marquis de Villette, père, had bought it, and then his son inherited it, along with the fortune and the title that went along with it. The Marquis de Villette, fils, hired the architect du jour, Charles de Wailly, for extravagant renovation and embellishment.

The building, then, set the stage for Voltaire’s last and arguably the best performance of his life. Hundreds if not thousands of people congregated daily by the front and side entrances of the townhouse, seeking the honor of a Voltairean audience. His philosophical friends were the first to be allowed in—d’Alembert, Condorcet, and Diderot—as were meritorious folk such as Benjamin Franklin and John Adams, who were in Paris trying to cajole Versailles into recognizing the rebellious government of the inchoate United States of America. The first time that Franklin and Voltaire met at the hôtel de Villette, Franklin asked the philosopher to bless his grandson, eighteen-year-old Temple Franklin, who was so tall he had to kneel before the skinny old deist. Voltaire, who recognized a theatrical event if ever there was one, put a bony hand on the handsome young man’s long wavy brown locks and pronounced solemnly, in English: “God and Liberty.” There wasn’t a dry eye in the house.

I would imagine that the tears of the sensitive and histrionic Marquis de Villette flowed most copiously. He was forever reminding people of an old rumor that Voltaire had been in love with his mother, the beautiful and engaging Marquise de Villette, during the time that he was conceived. That Villette was also a dabbler in literature was—for him!—further proof that he was the probable progeny of the great Voltaire. Villette repeatedly visited the exiled Voltaire in his domain of Ferney, which straddled the border between France and Geneva, then a republic. Rumored father and son passed the time playing chess, depilating each other’s sparse beard hairs, and talking shop. Charles Michel, Marquis de Villette, left us a few works of poetry in virtue of which Voltaire christened him “le nouveau Tibulle.” I had to look up the identity of the Old Tibullus: a Latin poet from a few years BCE whose verses proclaim his amours with women as well as with young men. I find his poetry in praise of men to be more persuasive. Villette also left us his correspondence and a personal account of the French Revolution. Best of all, as a future Revolutionary, Villette bequeathed to the ages a story of dramatic import: publicly burning his “lettres de noblesse,” for which his father had paid a fortune.

Voltaire lived in the luxurious townhouse of the wealthy Marquis de Villette for four months, which is how long he had to live. If he recognized the “Tibullian” intricacies of Villette’s sexuality, he does not seem to have been overly concerned to be living in his house—even with the Marquis de Thibouville sharing the premises. I was eager to find out if Voltaire championed his friends’ sexuality in the same way that he championed tolerance toward others who were shunned: victims of religion, or of injustice or superstition. Where was the literature, if any, that Voltaire left as his legacy concerning the tolerance for “les invertis,” to introduce another contemporary expression?

Part of the answer lies in another layer of complexity that caught my eye in Voltaire’s relationship with his friend/son. During one of Villette’s visits to Voltaire’s sanctuary in Ferney, the philosopher decided that Villette, at 42 years of age, needed to get serious and create philosopher-children to continue his dynasty. The end result was marriage for Villette—something that Voltaire never tried himself—to one of the adopted orphans he raised in his château: the beautiful and intelligent nineteen-year-old Reine Philiberte Rouph de Varicourt, called by her adoptive father’s pet name “Belle et Bonne.” Voltaire writes: “I die happy having been able to contribute to the happiness of two people, one of whom is full of wit and charm and the most amiable of men in high society, never having had anything to reproach himself save for a few pardonable weaknesses, and the other is innocence itself, virtue, prudence and goodness melded together.” What these “few pardonable weaknesses” were, Voltaire would not reveal. However, other members of high society might recall a few details about the Marquis de Villette: indecorous flings and indiscreet trysts with actresses ending in duels to which the Marquis would simply not show up.

They were probably just feints to throw society off the scent of his real indiscretions, which were known at first only to the constabulary. Police lieutenant Jean-Charles-Pierre Lenoir had twice caught the Marquis de Villette in compromising situations with men in the shrubbery of the Jardin des Tuileries, not too far from where the cruising area is situated today, as I found out from my extended research. Anxious to maintain public order, Lenoir was able to arrest the commoners of this trysting place but not the nobleman himself, who was above the law. Lenoir, however, was able to persuade one of the plebs, Villette’s secretary, Carrier, into spying on his master for a period of time. Villette’s free range in the gardens must have been curtailed by the informant’s revelations, for we hear of no further dalliances. This could also be due to the thickets and the bowers having been uprooted in an attempt, in turn, to uproot “the shameful industry of Sodom” and to thwart “its fanatics who prowled the garden paths.” However, the hallowed grounds of the Père Lachaise Cemetery remained available, as they are today, for nocturnal interludes among the overgrown crypts.

Despite Voltaire’s enthusiasm to join in marriage two of his favorite people, it was not an inspired union. Even though it engendered at least two daughters and a son—the requisite heir!—alas, there was to be no enduring happiness for either parent. Perhaps the Marquis de Villette had relied on the naïveté of “Belle et Bonne” to enable him to perpetuate his secret liaison with the Marquis de Thibouville under the same roof. It is doubtful that the Marquise de Villette ever became aware of her husband’s infidelities with a man. Voltaire, however, must have been mindful of the Marquis’ proclivities. He writes to his friend and fellow philosophe Jean le Rond d’Alembert: “M. de Villette has consummated his marriage. … It is a beautiful conversion that will be a great honor for philosophy, if it lasts.” D’Alembert responds: “This convert needs, in order to assure his conversion, to spend several months in your church, and to go to you for his catechism. I strongly wish that your instructions will complete this cure.”

Villette might have basked quietly in Voltaire’s aura for years, but he could not silence the clarion call of his nature. Hiding his sexuality under a bushel was not one of his talents. Eventually, Villette came out of the armoire (there were no closets in those days), and his lust for other men became widely known. Even the Marquis de Sade came up with a quip about Villette: when a new type of carriage became popular, Sade baptized it “voiture à la Villette,” since one entered it from the rear.

Voltaire never quipped about Villette, although he did perhaps, just once, quip about Thibouville in his long satirical poem, The Maid of Orleans. Here is my quick translation, but not in rhyming decasyllabic couplets:

Such have been seen like Thibouville and Villars,

Imitators of the first of the Caesars,

All inflamed by the fire that possesses them,

Head lowered, waiting for Nicomedes;

And assisting, by frequent lunges,

The valiant thrusts of their Picardian lackeys.

In case you prefer an older interpretation in verse, here is one from 1899:

So we are told Thibouville and Villars,

Who imitated Caesar from afar,

Inflamed by the fire which was their fate,

With lowered heads would Nicomander wait,

And frequently with vigorous emprise

Their Picard lackeys’ bodies fertilize.

(I think this version gets it backwards.) And here’s a more contemporary version, in prose, from 1758: “Thus Thibouville and Villars, in imitation of the first Caesar, when devoured by the fire of unnatural lust, with heads declined, sigh for the loved insertion of their Nicomedeses, and dexterously second the home efforts of their vigorous lacqueys.”

The Maid of Orleans has such a convoluted history that a quick summary might be helpful. Voltaire started his satire on Joan of Arc in 1730 and passed it around to friends in manuscript form. Never did he dream of publishing it, as such an irreverent text would have brought him more grief than it was worth. However, so many spurious versions were published—in London, Liège, Frankfurt, Amsterdam, and Paris—that Voltaire decided to publish his own official version in 1762, from which the most scurrilous portions were expunged. Thibouville must have forgiven Voltaire for the offending passage, or believed that these verses did not come from his quill, for their correspondence continued unabated until Voltaire’s return to Paris and his move into Villette’s home.

There is no evidence that Voltaire shared his friends’ sexual proclivities. He was too busy extolling the “big tits” and “succulent ass” of Madame Denis, his niece, who was his junior by eighteen years. Still, his treatment of the “anti-physique” theme is everywhere in his works, such as in an article titled “Amour nommé Socratique” in his Philosophical Dictionary; the scenes in Candide in which Cunegonde’s brother—an aristocrat, a priest, and a homosexual, in that order—appears. There is no underlying criticism, no judgment about the baron of Thunder-ten-Tronckh’s homosexuality. Instead, what Voltaire criticizes mercilessly is that the baron is simultaneously a nobleman and a clergyman—the “infamy” in his “Écrasez l’Infâme!” One can surmise why homosexuals were not targets of Voltaire’s reproach: they played no role in curtailing the rights of others in society or denying the oppressed the possibility of bread and happiness. Voltaire cared less about sexual orientation than about the favoritism and privilege enjoyed by the nobility and the clergy.

Two of Voltaire’s best friends were gay, and I have my suspicions about a third, the Marquis d’Argenson, the creator of the Arsenal Library. The three of them were among those he called his “angels,” who helped him to vanquish his enemies. With his trademark tolerance and humanity, Voltaire accepted his gay friends with aplomb, created gay characters who were villainous for other reasons, and lived his final days succored, and loved, by intimate friends who were “anti-physiques.”

Roy Luna, a retired professor of French literature living in Miami, is the author of a trilogy of historical novels, of which the third, His Fellow Librarian, will be out in April.

Guess Who Hosted Voltaire in Paris

0Published in: March-April 2018 issue.