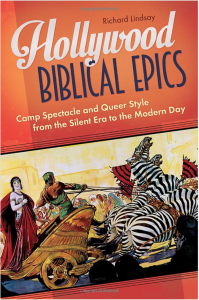

“WHO IS THE WOMAN on the cover,” Richard Lindsay asks in the opening line of his book on Bible-based epic movies, “and why is she in a chariot being drawn by zebras?” (See book cover on page 12.)

Well, the simplest answer is that she’s on a billboard-sized movie poster that Cecil B. DeMille used to promote his 1927 silent film The King of Kings. And the reason she’s in the movie in the first place is that DeMille was worried that he would only get the religious-minded for his audience, when he wanted the “Broadway crowd” to see it. That, presumably, is why The King of Kings premiered at the Gaiety Theater in Times Square in 1927, when Times Square was a magnet for urban sophisticates, not to mention a hotbed of what would later be called gay men. (The Gaiety is the name of a theater where gay men were going sixty years later to watch male strippers come out at the finale in a chorus line with full erections they wagged in the audience’s faces. Could it be the same place?)

The woman with the zebras is on the cover, finally, because, in his desire to snag the Broadway crowd, DeMille began his film not with a religious scene but with a prologue showing Mary Magdalene as a harlot at home in her palace. Not only is she having an affair with Judas Iscariot, but also, on hearing that Judas isn’t on the couch beside her because he’s been hanging out with Jesus, she decides to go find him—which leads her to order the servants: “Harness my zebras—gift of the Nubian king! This Carpenter shall learn that He cannot hold a man from Mary Magdalene!” Surely “Harness My Zebras” is the title Lindsay would have wanted for his book had cooler heads in editorial not prevailed. I say this because that title captures the element of “camp” that he regards as crucial to the viewer’s conflation of these movies with actual Scripture—though one would think camp would have the opposite effect on taking these things seriously.

Hollywood Biblical Epics is divided into two parts. The first compares The King of Kings, one  of the earliest epics, with Mel Gibson’s The Passion of the Christ (2004), one of the most recent. The first chapter examines the way both were marketed to the religious establishment before being released and the way people began to regard these films as forms of Scripture itself. In the second part we’re in the golden age of the biblical epic, the ’50s and early ’60s, when, Lindsay argues, such films began exploiting American anxieties about Communism and homosexuality through the lens of religious narratives—since biblical epics were usually set in Rome at the height of its power (which is when Christianity began to make inroads), and the U.S. has always compared itself to Rome. Indeed, after World War II, Americans suddenly found themselves with an empire of their own, which means they began worrying that they too might be decadent—and what was more decadent than homosexuals? By the last chapter, devoted to Ben-Hur, it’s too late, as Lindsay tells it: the cult of the muscular male in all of these movies had led to the posing strap magazines and arguably to gay liberation itself. Along the way, we see how Hollywood used biblical subject matter as a way to deliver sex, violence, and spectacle while avoiding the censorship of the Production Code (a code written, ironically, by a Jesuit priest who worked as an advisor on The King of Kings).

of the earliest epics, with Mel Gibson’s The Passion of the Christ (2004), one of the most recent. The first chapter examines the way both were marketed to the religious establishment before being released and the way people began to regard these films as forms of Scripture itself. In the second part we’re in the golden age of the biblical epic, the ’50s and early ’60s, when, Lindsay argues, such films began exploiting American anxieties about Communism and homosexuality through the lens of religious narratives—since biblical epics were usually set in Rome at the height of its power (which is when Christianity began to make inroads), and the U.S. has always compared itself to Rome. Indeed, after World War II, Americans suddenly found themselves with an empire of their own, which means they began worrying that they too might be decadent—and what was more decadent than homosexuals? By the last chapter, devoted to Ben-Hur, it’s too late, as Lindsay tells it: the cult of the muscular male in all of these movies had led to the posing strap magazines and arguably to gay liberation itself. Along the way, we see how Hollywood used biblical subject matter as a way to deliver sex, violence, and spectacle while avoiding the censorship of the Production Code (a code written, ironically, by a Jesuit priest who worked as an advisor on The King of Kings).

There seem to have been two golden ages of the biblical epics: first, the early silent film era and the early talkies (Ben-Hur, among others, was made both ways); and a later one that began when DeMille made Samson and Delilah in 1949—which started a run of movies (David and Bathsheba, The Big Fisherman, The Silver Chalice, Quo Vadis, Ben-Hur, The Robe, Demetrius and the Gladiators) that did not end till 1965 with George Steven’s The Greatest Story Ever Told, a box office dud that was, Lindsay says, so reverent it was not even camp—an essential ingredient in the successful epic in his view. The last epic to do well was John Huston’s The Bible: In the Beginning (1966), but it tied that year with Hawaii and Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, the latter being the film that Lindsay says “essentially marked the end of the Production Code.” He also gives Cardinal Spellman credit for that, for overreaching when he called Elia Kazan’s film Baby Doll an attack on the American way of life.

Whatever the cause, Lindsay writes, “once Hollywood could get away with sex and violence without couching these elements in the guise of the Bible, there was no longer a need for theatrical release biblical films.” That is, until, after a long drought, Mel Gibson’s The Passion of the Christ “took the Crucifixion as an alibi to release perhaps the most intimately violent film ever created—the systematic destruction of a single human body—without even being tarred with the box-office kiss-of-death NC-17 rating.” Gibson’s film is an illustration of Lindsay’s argument that biblical epics were successful “because of their violent, sadomasochistic, and orgiastic content, not in spite of it”—though The Passion of the Christ is grimly bloody to a degree its predecessors never were. The old biblical epics were captivating spectacles—of dancing girls, muscle men, palaces, jewels, scarves, goblets, and grapes: Alma-Tadema paintings come to life. They were thrilling and fun, at least to me when I was twelve years old, though I had not even heard of the word “camp.” Biblical epics were everything that democratic, middle-class, ordinary American life was not.

By the time I’d grown up, I’d learned that Groucho Marx had dismissed these extravaganzas with a funny line: “I don’t want to go to any movie where the men’s tits are bigger than the women’s”—though one learns from Lindsay that what Groucho actually said, when DeMille asked how he liked Samson and Delilah, was: “No picture can hold my interest where the leading man’s tits are bigger than the leading lady’s.” Ah, the disillusion of adulthood—and the accurate quote! Whenever I ran into a certain person in the Meat Rack on Fire Island, he would murmur a line from The Ten Commandments: “I don’t believe I’ve seen you in the pits before”—but after Googling, I find that what the love interest actually says when she finds Moses toiling in the quarry is, “You are strange to the pits. Your back is unscarred,” a line that would probably be more apropos at an S/M orgy. But Groucho was right: another reason a gay boy might like these biblical epics was, of course, the spotlight on the muscular male chest—Charlton Heston’s, Victor Mature’s, all those extras’. Nothing’s funnier than the photo included here of DeMille, looking like Harry Truman as he stands with his hands on his hips before row upon row of the biggest, smoothest, oiliest chests in Hollywood. (The illustrations in this book, though less than glossy, are a delight.)

There were muscles everywhere in these movies—though masculinity, of course, had nothing to do with it. In one of the delicious asides that pepper this book, we learn that DeMille held Victor Mature in contempt because he refused to wrestle a lion that had been shown to be entirely tame. Or, as Lindsay puts it: “At some point, the raw spectacle of exposed male bodies begins to undermine the very assumptions about the gender roles ‘holy’ men are supposed to play.” But if the men with the big pecs were not entirely fearless, there was no doubt about the villains. The bad guys, to whom Lindsay devotes an entire chapter, were all flaming queens: Charles Laughton’s Nero in The Sign of the Cross (1932), his Herod in Salome (1953), Vincent Price’s Egyptian overseer in The Ten Commandments (1956), Jay Robinson’s Caligula in The Robe (1953), and, finally, Peter Ustinov’s amazing Nero in Quo Vadis (1951).

Ustinov’s Nero seemed to illustrate every one of the characteristics that Austrian psychiatrist Edmund Bergler claimed all homosexuals exhibited, according to Lindsay: “masochistic provocation and injustice collection; defensive malice; flippancy covering depression and guilt; hyper-narcissism and superciliousness; refusal to acknowledge accepted standards in non-sexual matters; and general unreliability … of a more or less psychopathic nature.” All of which reach their climax when Ustinov’s Nero, suspected of setting Rome on fire in order to give himself an artistic subject worthy of his talents, is told by his adviser Petronius that the mob rushing the palace is fleeing because “They want to survive,” and Nero replies: “Who asked them to survive?”

Nero, Caligula, Herod, the Egyptian overseers in The Ten Commandments—all are vicious, narcissistic, psychopathic, homosexual monsters—and all are dead by their film’s end. It was so common to kill off homosexual characters in Hollywood movies that the indispensable Vito Russo made a list in The Celluloid Closet of the various means by which it was done. Fittingly, it was during a documentary based on Russo’s book that scriptwriter Gore Vidal claimed he’d written an unrequited homosexual love story into Ben-Hur that provides a motivation for the rivalry between the hero and his Roman counterpart, Massala—a claim that Charlton Heston (who made so many biblical epics he became a biblical prophet himself, before turning to Planet of the Apes and the National Rifle Association) contested in an exchange of letters with Vidal in The Los Angeles Times.

Lindsay devotes a whole chapter to Ben-Hur, not only because it was a box office smash that won eleven Academy Awards, but also because, unlike the other epics, it contains hardly a hint of heterosexual romance. The script is all about relationships between men, even though it was filmed in an era when shrinks like Bergler claimed: “There are no healthy homosexuals.”

Analyzing in his afterword our most recent crop of biblical epics—Noah; Exodus: Gods and Kings—Lindsay finds that the delicate recipe that made their forerunners so effective has been lost. Some of the new ones are too camp, he says, and some not camp enough. To succeed, a biblical epic has to be somewhere between the two. But what made the classic epics just right? Was the element of camp present in the intentions of the film makers, or only in the perceptions of the proto-gay audience? Did DeMille think his work was camp? Surely he didn’t want his epics to be made fun of. And what is camp, anyway? Why is “Harness my zebras” funny? Or “Oh Moses, Moses, you stubborn, splendid, adorable fool!” Or the moment, during auditions for Ben-Hur, when the actors were asked: “Have you driven a chariot?” The anachronism, the pomposity, the grandiloquence?

When Charles Ludlam of the Ridiculous Theatrical Company celebrated all this in his play Salammbo (1985), the production had so many muscle men that there were problems backstage from the farts emitted by all the health-food-eating body builders he had recruited at the Sheridan Square Gym. But while the incomparable Ludlam draped himself in pearls and silk and lots of eyeliner, lounged upon a couch like Mary Magdalene, and spared no effort in sets and costumes, the curious thing is that the play wasn’t very funny. Perhaps camp cannot be based on camp. Or maybe Ludlam had sipped the Kool-Aid of the ancient world, like his inspiration, Flaubert, for that matter, whose novel of the same name is a feverish dream of Orientalism. There is something about the ancient world that tempts artists at their peril. Even Norman Mailer spent ten years writing an Egyptian clunker called Ancient Evenings.

Eventually, a reaction set in. When Paul Newman, star of The Silver Chalice, replied upon being asked if he would do a second biblical epic, “I’ll never make another movie wearing a cocktail dress,” that was a sign that everyone was now in on the joke. Like The Silver Chalice itself—which features not only the young Newman’s Grecian beauty but also a bravura performance by Jack Palance as a magician determined to perform miracles that outdo Christ’s—this remark was, in Lindsay’s opinion, too camp for its own good.

In the end, however, one isn’t sure what role camp played in these biblical epics, especially at the time they were made. Lindsay admits in his preface that a definition of camp is hard to pin down. Yet he feels camp is the heart of the matter: “Biblical films are … both essential and frivolous, holy and blasphemous. Which is to say there is no better way to read them than through the lens of camp.” And: “Films like The King of Kings and The Ten Commandments have led audiences to expect sex, violence, and spectacle in biblical stories, to the point that camp has become a defining element of the genre.” But what does this mean, that sex and violence are themselves camp? Or just the ham-handed, corny way they are depicted? Or the fact that they were delivered to the audience under the guise of Scripture? DeMille took great pains with the ingredients of his movies. He did not portray Palm Sunday in The King of Kings, Lindsay tells us, for purely cinematic reasons. He told the cast and crew: “That is one thing I have against Jesus Christ, from the standpoint of moving pictures. He did something we cannot show on screen, the picture of [a]heroic conqueror entering a city on a donkey.” (One can only imagine Jesus replying, with hand on hip, “Well, pardonnez-moi!”) Perhaps it was the hypocrisy, the corny excess, that now seems camp. Maybe camp is what releases you from credulity, from an allegiance to a work of art—the moment when you see the fakery, a reality check—or just the tackiness of excess: too many muscles, too many zebras, too many grapes.

Whatever the role of camp in all of this, Hollywood Biblical Epics brings together strains of gay and cinematic history that make for a very entertaining tour of American culture. To learn that DeMille, when his film came out, paid for stone monuments of The Ten Commandments to be erected in towns all over the country, some of which are still standing in front of courthouses, like the one in Austin, Texas, which survived a constitutional challenge, is part of it. To think that, during puberty, when I fell under the spell of movies like The Robe and Quo Vadis, I was being indoctrinated against the evils of Communism while remaining unaware that I was something Americans found as repulsive as the Bolsheviks, is fascinating. I thought I was just being transported by Jesus and the ancient world.

Biblical epics, alas, are not being made much anymore. But for anyone who grew up in the ’50s and ’60s, they will always incite nostalgia, for the books they were based on were a very big part of American movie-going back then. Consider the essay Gore Vidal wrote after reading every book on The New York Times Bestseller List: as late as 1973, it included historical novels with Christian storylines. American culture was simply more Bible-based then. For a twelve-year-old in the late ’50s, there was one book after another: Quo Vadis, The Robe, The Silver Chalice, The Big Fisherman. Writers like Taylor Caldwell and Lloyd C. Douglas sold hundreds of thousands of copies. From sixth to eighth grade, there was nothing more spell-binding than those huge novels, and the movies made from them in which the central figure, Christ, was usually not shown but only glimpsed, as a hand lifting someone up, or a man seen from behind, but never, as they say now about nudity, full-frontal. Now, of course, that culture has been replaced. Despite all the surveys claiming that most Americans still consider themselves Christians, the public culture at this moment is really post-religious.

Nevertheless, whenever cinematic technology advances, Lindsay points out, biblical epics are remade, if only to create new special effects, which, like the parting of the Red Sea in DeMille’s Ten Commandments, have always been essential to these films. The Ten Commandments itself, he tells us in an afterword, is being redone. And a new version of Ben-Hur is coming out in 2016. But what on earth can their effect be now? The country into which they will emerge is so different from the one in which the originals appeared. Gays have come out, everyone knows what camp is, there are many people who no longer believe that Jesus was divine, and religion itself, especially in places where it goes along with murderous homophobia, has never, given the nihilistic cruelty of the jihadists, been so discredited, so exposed as a mask for sex and sadism—just like, you might say, the biblical epics themselves.

Andrew Holleran’s novels include Dancer from the Dance, Grief, and The Beauty of Men.