Forever Stardust: David Bowie Across the Universe

Forever Stardust: David Bowie Across the Universe

by Will Brooker

I.B. Taurus. 259 pages, $22.95

WHEN I interviewed filmmaker Duncan Jones, who also happens to be the son of David Bowie, I closed the interview with this question: Did it ever weird him out that so many gay journalists told him that the first time they dyed their hair blond was because of his father? Jones met the question with a laugh, but for gay men of a certain generation, Bowie was one of the most serious defenses against homophobia one could have. There he was: an undeniably brilliant artist, performer, and rock-and-roll icon—who had boasted brazenly of his sexual conquests of men.

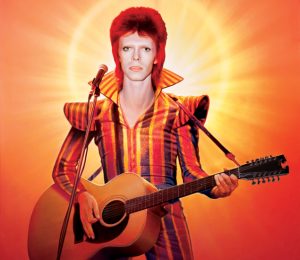

Following his shocking death last year at age 69, some people criticized the obituaries for downplaying or neglecting to mention Bowie’s gender outlaw status. It’s hard to imagine how anyone could have missed it, given the cross-dressing, the makeup, and the lusty lyrics, not to mention the photos of Bowie cuddling with Lou Reed and Mick Jagger at Studio 54, or the over-the-top homoerotic role he played in Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence. Thankfully, author Will Brooker gets into a thoughtful and pleasing analysis of Bowie’s substantive style in Forever Stardust, a book that manages to be written from the perspective of an obvious fan who is never fawning or shallow.

Brooker’s strategy is to leap about in time and space as he writes, picking up on different themes to which Bowie would return. His book will hold appeal for all Bowie enthusiasts regardless of their gender identity or position on the Kinsey Scale, but readers of this  magazine may be most interested in what is in fact the most compelling chapter: “Gender and Sexuality.” Brooker begins by unpacking many of the accolades made in the days and weeks following Bowie’s death. Obituary writers, perhaps constrained by both space and time, were quick to conflate Bowie’s extensive gender play, including cross-dressing and donning of makeup, with his expressions of same-sex desire or his bisexuality. But the two—gender identity and sexual orientation—are two distinct things, as Brooker understands.

magazine may be most interested in what is in fact the most compelling chapter: “Gender and Sexuality.” Brooker begins by unpacking many of the accolades made in the days and weeks following Bowie’s death. Obituary writers, perhaps constrained by both space and time, were quick to conflate Bowie’s extensive gender play, including cross-dressing and donning of makeup, with his expressions of same-sex desire or his bisexuality. But the two—gender identity and sexual orientation—are two distinct things, as Brooker understands.

Brooker also understands that an artist whose themes and messages were so intricate deserves to be treated with detailed analysis. He notes that Bowie’s repeated use of the alien motif—that he had been dropped here from some other planet, as the title of the cult movie The Man Who Fell to Earth suggested—had a paradoxical effect on his fans: it was this very otherworldly status that made them feel less alone. Bowie’s various personæ explain why such a range of people on the margins of society felt connected to him.

The highlight of this chapter is its measured examination of the moment that all queer Bowie fans of a certain age will never forget: the 1983 Rolling Stone cover story in which the artist revealed another new persona, this one decidedly heterosexual, in which he basically dismissed his previous statements about being gay or bi as “experimenting.” In other words, it was all just a phase. Adding to it all was the magazine’s cover headline, which read “David Bowie Straight.” At the dawn of the AIDS crisis, this could not be ignored or denied. I still recall looking at the cover on the newsstand: “If the fearless Bowie is running scared,” I thought to myself, “then this is even more horrifying than I’d imagined.”

Brooker’s conclusions are not judgmental, but somewhat damning nonetheless. He points out that much of Bowie’s initial flirtation with gender play and nods to being bent were just ways of getting attention and driving up record sales. The ruse worked beautifully, until Bowie started pushing into the American mainstream market, where tastes were far more conservative and less tolerant. Brooker finds subsequent interviews with Bowie in which he says his motivation for many of the statements in the Rolling Stone interview were made for that very reason: to pave the way for his biggest mainstream success, the Let’s Dance album and subsequent “Serious Moonlight” tour.

Brooker’s writing style and tone are inviting, and his intelligence and extensive research breathe life into every page of Forever Stardust. He is to be commended for acknowledging the enigmas surrounding an artist as complex as Bowie. Like most great artists, Bowie led a life and created a body of work that is riddled with contradictions. As Brooker contends, his connection and meaning to LGBT spectators will remain one of his enduring mysteries.

Matthew Hays is the co-editor (with Tom Waugh) of the “Queer Film Classics” book series.