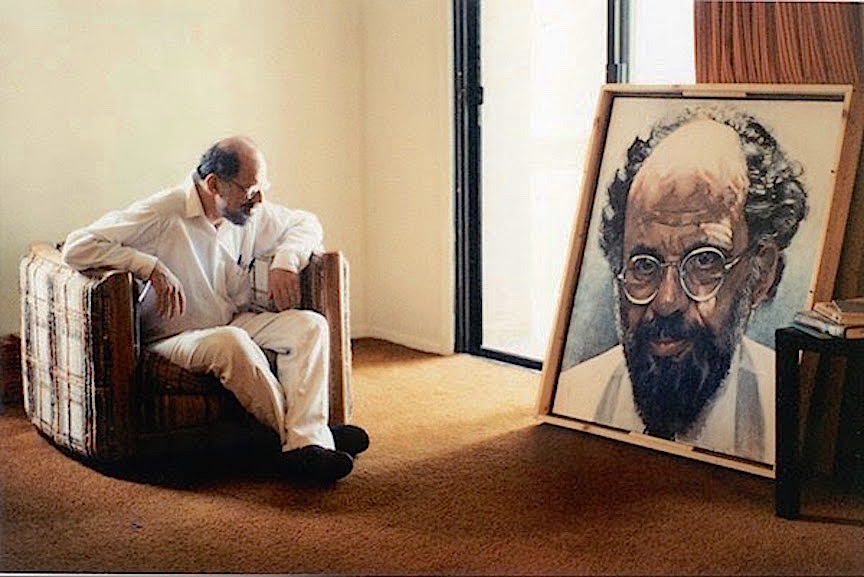

The Best Minds of My Generation: A Literary History of the Beats

The Best Minds of My Generation: A Literary History of the Beats

by Allen Ginsberg

Edited by Bill Morgan

Grove Press. 460 pages, $27.

First Thought: Conversations with Allen Ginsberg

First Thought: Conversations with Allen Ginsberg

Edited by Michael Schumacher

Minnesota. 280 pages, $19.95

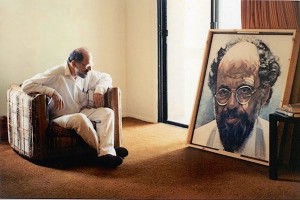

BOB DYLAN called him “a lyrical genius, con-man extraordinaire, and probably the single greatest influence on American poetical voice since Walt Whitman.” Others reviled him and his coterie as “Know Nothing Bohemians,” a bunch of misfits. What goes unquestioned is that Allen Ginsberg, who died twenty years ago, was a major cultural lion, not only in the U.S. but around the world. Ginsberg saw himself and his fellow Beats—among them Jack Kerouac and Williams S. Burroughs—as “prophets howling in the Wilderness against a crazy civilization.” His 1956 poem Howl, a scathing jeremiad against the destruction of “the best minds of my generation,” forever changed our notion of what a poem can be. Beyond the influence that his “spontaneous bop prosody” had on poetry, Ginsberg’s formidable voice and intellect—by turns sweet, angry, outrageous, and prophetic—has informed many areas of contemporary life, from the various liberation movements, ecological awareness, and opposition to the military-industrial complex, to the lyrics of Bob Dylan.

Ginsberg’s star continues to rise. Since his death, publishers have brought out dozens of new books, including new editions of his poems and various collections of his letters. Two years ago, Harper Perennial published an Essential Ginsberg, an anthology of poems, essays, letters, songs, and photographs, which aimed to capture the “prolific and profound diversity” of this protean artist, who eludes simple pigeonholing.

And now this year, two more Ginsberg books have arrived on the scene. The Best Minds of My Generation: A Literary History of the Beats is a compendium of lectures Ginsberg delivered at the Naropa Institute in Boulder, Colorado. “No one knew the topic better than he did,” writes Bill Morgan, the book’s editor, who served as Ginsberg’s archivist and bibliographer, and who has written almost thirty books on the Beat Generation. The lectures were taped so that Ginsberg could later compile a complete documentary history of the Beat Generation. With his death in 1997, that task fell to Morgan, who personally transcribed the nearly 400,000 words. Morgan took what amounted to 2,000 pages of text and pared them down, eliminating repetition.

Ginsberg’s course was organized around a core group of writers that included Kerouac, Burroughs, Gregory Corso, and Herbert Huncke—writers whom Anne Waldman in her foreword calls Ginsberg’s “heart buddies.” The talks focused on key Beat texts, written mostly in the ’40s and ’50s. A tender nostalgia for those early years runs through many of the lectures. Ginsberg says that the young Beats “all had the same sort of divine ambition. We all had discovered how big the universe was, discovered death, had our first sexual tickle. … We began to discover that our own lives were mythological.”

Photo by Gordon Ball

The Beat Generation was primarily a spiritual movement, Ginsberg contends, one permeated by influences as diverse as Zen, psychedelic drugs, dreams, jazz, Times Square with its “fluorescent consciousness,” and Dostoevsky (“our favorite”). The Naropa talks were excursions into the spiritual breakthroughs or insights that members of the original Beats had articulated in their poetry and prose. For them, literature was “a noble means of investigation of our own minds and our natures and our emotions.”

Of the fifty topics in Best Minds, more than twenty focus on Jack Kerouac, who, Ginsberg said in the dedication page of Howl, was the “new Buddha of American prose.” The movement would not have happened, he told his students, if Kerouac hadn’t come along. “We would be just a bunch of amphetamine-head, faggot, jailbird professors.” Ginsberg’s esteem for Kerouac permeates the lectures. Even when he’s talking about other writers, he often comes back to Kerouac, whom he describes as “all enthusiasm, lyricism, innocence, fantastic ear and great heart.”

Ginsberg loved Kerouac’s playfulness with language—“hot hipster talk,” he called it—which rarely adhered to conventional literary rules, including the notion that prose should always make sense. “He could have had a nice career as a novelist, but instead he decided to write directly out of his brains rather than fill out a form like he was supposed to, to be reviewed in the New York Times.” Ginsberg addresses not only Kerouac’s breakthrough novel, On the Road, but the rest of his corpus as well. Of Visions of Cody, he reports that he “just wept” at the novel’s opening cadenza—a single sentence three pages long. “It seemed so orchestral.”

Ginsberg was a generous and often brilliant reader of his fellow Beats. But sometimes he would indulge in breathless encomiums—“brilliant,” “mind-blowing,” “completely knocked me out”—to praise a work beyond its due. To my mind, his reading of Gregory Corso’s poems falls into this category. Ginsberg deemed Corso a genius of “inharmonious discordant beauty,” a poète maudit of the “fiery lyre,” who threw “mind into chaos.” His several lectures on the poet gush with pæans to Corso’s imaginative leaps and surrealistic imagery. According to Ginsberg, one of Corso’s poems concludes “on the most fantastical Shakespearean line in hippie poetry.” Another sports “the best line in twentieth-century poetry.” This kind of hyperbole may have been fun to listen to at Naropa, but I’m not sure it bears the test of close scrutiny. Call me square, but most of Corso’s poems just don’t make much sense. Ginsberg is honest enough to admit that Corso’s “mouthfuls of language” are often mystifying, though he insists that the poet allowed chaos to enter his poetry in order to reveal “the beauty or wonder or strangeness of the actual world.” Well, maybe.

Williams S. Burroughs, the author of Naked Lunch and Junkie, is treated in ten more lectures. Compared to his talks on Kerouac, Ginsberg’s treatment of Burroughs often seems more dutiful than adoring. Burroughs was, Ginsberg says, the “picaresque adventurer,” more man of action than writer, who “took a lot of junk over the years” in order to go “to the end of his mind.” One sees Ginsberg trying to come to terms with Burroughs’ addictions to drugs and sex. He confesses that he might have turned out to be a junkie, too, “except that I observed Burroughs.” He downplays the role that drugs played in his own life. Acid and grass were, he insists, “a catalyst … but not a satisfactory conclusion to the search.”

Over the course of the Naropa lectures, the list of writers that Ginsberg eloquently discusses—Shakespeare, Joyce, Melville, Blake, Proust, Rimbaud—is impressive. That same erudition is prevalent in First Thought: Conversations with Allen Ginsberg. The interviews here collected by editor Michael Schumacher (like Morgan, a Ginsberg scholar) have never been included in previous collections, which makes this an especially important anthology. The eighteen pieces are replete with interesting and valuable information about Ginsberg and his career.

Figures who were important in the Beat movement but not covered in the Naropa lectures surface in these conversations. One is the Beat-Buddhist poet Gary Snyder, through whom Ginsberg “came to realize that the safest way of preparing the mind … is training in meditation.” In another, “A Conversation Between Ezra Pound and Allen Ginsberg” (1968), a subdued, depressed Pound, who was incarcerated after World War II on charges of treason, tells Ginsberg: “The worst mistake I made was that stupid, suburban prejudice of anti-Semitism.” To which Ginsberg, who seems always to have tried to find the humanity in others, tells the senior poet that he was at the beginning of Buddhist wisdom, and then proceeds to ask Pound for his blessing.

One of the most poignant pieces is a joint interview by Stephen Braitman with Ginsberg and his father Louis Ginsberg, a high school teacher and lyric poet of some distinction. Braitman asked each what they felt when they read the other’s poetry. “An almost tearful realization that I should have been kinder when we were around together,” the son declares.

In a 1987 interview with Steve Silberman, Ginsberg said that he wanted to be remembered as “an ecstatic poet” whose work “spread some sense of expansion of awareness, or expansive consciousness.” Like his poetic mentor Walt Whitman, Ginsberg dreamed of a nation composed of comrade democracy: “A bunch of macho competitors all hating each other, or indifferent to each other, or scared of each other emotionally, would leave no possibility of a cooperative, democratic, functioning political system,” he once said.

Ginsberg perennially aimed for “a deepening of heart rather than a shallowness of heart.” These two volumes reaffirm that radical, and necessary, humanity. His message—that “only with basic friendliness would it be possible for a nation to create a political world that was livable”—is as sorely needed today as it was during the heyday of the Beats.

Philip Gambone is the author of four books, including The Language We Use Up Here (Dutton) and Travels in a Gay Nation: Portraits of LGBTQ Americans (Wisconsin).