OVER TWO DAYS in November 1938, the Nazi Party and its allies orchestrated pogroms, attacking, arresting, and killing Jews; ransacking Jewish-owned stores; and burning synagogues across Germany. Kristallnacht, the “Night of Broken Glass,” is often cited as the beginning of the Holocaust and the murder of six million Jews, including almost all my parents’ relatives. But it was not until I learned of the pogroms’ queer significance that these events began to obsess me. That was about 1990, when I picked up a book on Kristallnacht. While it was the first one I read on the topic, it would not be the last: The number of volumes dedicated to its horrors has grown over the years, and most of them make at least some reference to homosexuality.

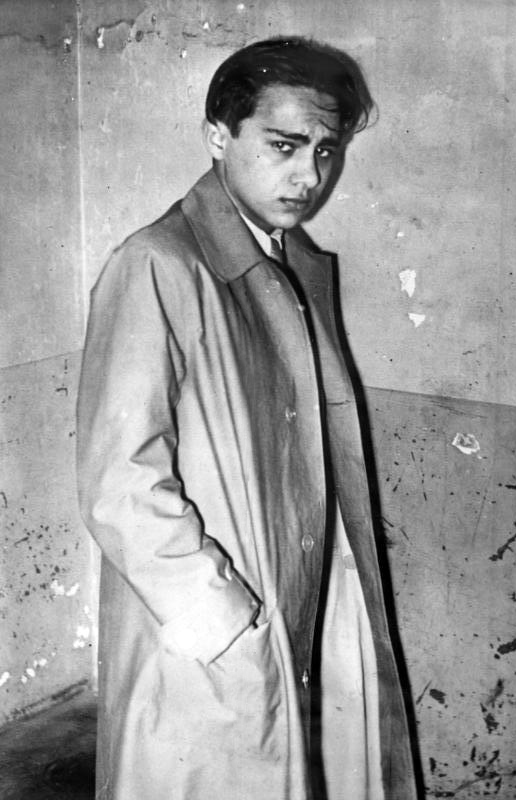

Back in Germany, the Nazi party, often working with the police, used vom Rath’s death as an excuse to prompt scores of “spontaneous” uprisings and attacks on numerous communities. Herschel was held up as an example of the international Jew while vom Rath was enshrined as the flower of Aryan manhood. Herschel turned himself in and was jailed. After France fell in 1940, he was seized by the Germans, who began preparing for a massive public show trial.

While there was some evidence that vom Rath may have been gay, what really frightened the Nazi regime and sent a panicked Joseph Goebbels confiding to his diary was that Herschel was changing his testimony, stating that the crime was not political. He and vom Rath had been involved sexually, he claimed. A Jew and a German in love? The pride of German manhood queer? The leaders of the Reich panicked. There was no trial, and Herschel disappeared, leaving historians perplexed as to how to tell the story. Many state that it was Herschel’s brilliant lawyer, Vincent de Moro-Giafferi, who convinced Herschel to depoliticize the crime and instead confess to being gay, tarnishing vom Rath for seducing a minor and bringing shame on the Nazis.

As I read more, I was intrigued—and angered. All historians toed that party line—agreeing that of course Herschel could not have been gay. The lad was less of an innocent victim and not so heroic if these were the actions of a homosexual lover. Their denials made me wonder: What if Herschel was telling the truth? I had written two novels by then, my lover Olin Jolley had AIDS, and I could see parallels between being a hated Jew in World War II Europe and a person with HIV in a country contemptuous of such people.

I was a historian to some extent, but this was not my field; maybe in a novel I could tell Herschel’s story and try to reconcile all the contradictory versions of it. Maybe he was gay and maybe his attorney, not knowing that, did tell him to make up a story; maybe his relationship with vom Rath, if it existed, was not tawdry, as everyone who entertained the possibility believed it had to be. What a situation for a young man—to be in prison, blamed for setting the world on fire, trying to show his family he had been a martyr for them, while knowing if he said that, he would be put to death and Jews punished further. Worse still, what if he had loved the man he killed?

I’m not here to say whether the novel I wrote did justice to Herschel or its themes. It went the rounds for years; editors praised but would not publish it. One day a major New York house committed to it verbally; the next week the offer was withdrawn. There was the fear, I was told, that saying Herschel was gay would somehow minimize the horrors of the Holocaust. Olin died in 1996, and I gave up for a while. But in 2005 my novel was published by a university press. It got some good reviews; a movie option came to naught. A few months ago, I read a self-published novel in which, again, it was acknowledged that vom Rath was gay and he and Herschel were friends, but of course the hero of the story couldn’t be queer.

But he was. I believe what a family member of Herschel’s told me. In 2009, an email appeared in my inbox from a Jewish woman in Australia who’d been sent a clipping about my book by her rabbi. She had previously told him about her mother’s relative Herschel Grynszpan. Her mother had grown up with him. “She always told me the story you have verified, that he was homosexual,” this woman wrote. “My mother always suspected an entanglement with a Nazi officer.” Ironically, her mother was also caught up in the events of Kristallnacht, then living in Hanover, Germany, where Herschel’s family had lived before their deportation. Feeling somewhat vindicated that I had not toyed too much with the facts, I thanked my correspondent for her honesty. She told me her mother’s papers are in an Australian library. I worked in archives for fifty years and know well that they often hold the keys to mysteries.

Herschel vanished in 1942; at the request of his family, he was declared dead by the West German government in 1960. The next year, Herschel’s father testified in Jerusalem at the trial of Adolf Eichmann. Rumors flew that Herschel was alive; if he was still in Germany, he could be jailed for being gay. In 2016, uncatalogued photographs taken in 1946 of crowds in a displaced persons camp surfaced in an archive; one showed a man who looked like Herschel. According to one source, face-recognition technology said there was a 95 percent chance the man photographed was Grynszpan.

Mysteries abound; truth is often sought and even sometimes found. The time has long passed for historians to be afraid of homosexuality. But today—and I’m glad my parents and my lover did not live to see this—trans and other members of our community are being told they cannot be heroes or fight for their rights or their country. Demonization and erasure continue. The tragedy (and mystery) of Herschel Grynszpan does, too.

Harlan Greene, who published The German Officer’s Boy in 2005, is the author of the new biography Porgy’s Ghost: The Life and Works of Dorothy Heyward (2025).