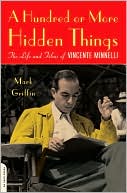

A Hundred or More Hidden Things: The

A Hundred or More Hidden Things: The

Life and Films of Vincente Minnelli

by Mark Griffin

Da Capo Press

368 pages, $15.95 (paper)

MARK GRIFFIN was inspired by the work of Vincente Minnelli one summer when, as a misfit 16-year-old with little confidence, he watched the director’s penultimate film, On a Clear Day You Can See Forever. The story of a clairvoyant, chain-smoking student, whose own dowdy personality was eclipsed by her glamorous past-life persona as a 19th-century coquette, appealed to the young Griffin, who identified with the character’s struggle to achieve self-acceptance. He watched the movie repeatedly, and went back to high school with newfound assurance.

Griffin traces Minnelli’s ambitious rise to fame, starting in childhood as he traveled with his family’s “portable theatre” to little towns in Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois, where he showed an interest in drawing sketches and designing costumes. Griffin follows Minnelli’s stint in Chicago working as a window display designer at Marshall Field, which is where he also adopted the name “Vincente” and shaved a few years off his age. Also, by the author’s account, he “almost certainly embarked on a relationship with another man—one named Lester Gaba.” Quoting Morton Myles, a friend of Gaba’s: “Lester always maintained that he had some kind of dalliance or liaison with Minnelli. I can’t say yes or no for certain, but he always alluded to the fact that they had an affair.”

Further rumors about Minnelli’s sexuality were uncovered regarding the time he worked as chief costume designer and art director at Radio City Music Hall. According to designer Jack Hurd, “Next door to Radio City, at Rockefeller Center, there’s a skating rink. That’s what they call a cruising spot for gay pick-ups. Well, he picked me up there one evening and brought me back to his apartment. He showed me models of sets and things, which he had around the apartment. Then he wanted to have sex but I didn’t find him attractive. He had make-up on. He was too feminine. So, I left. … Years later, after the war, I ran into him between the sound stages at MGM, where I was then working on sets. I reminded him of what took place years ago and oh, god, … he went to L.B. Mayer and he wanted to get me fired. He didn’t want me around. And he was still freakish, wearing make-up—lipstick and eye stuff. He was married to Judy Garland by then and everybody would say, ‘What the hell does she see in him?’”

Minnelli later directed three successful shows for the Schuberts, making him “the toast of Broadway.” In 1940, his serendipitous arrival at MGM’s “Freed Unit” brought an auspicious start to his professional life in Hollywood. Minnelli lent his self-professed “small but exquisite talent” to Freed for over a year, and the producer went to bat for Minnelli, who caught his first directorial break with Cabin in the Sky, an all-black musical. As he does with the rest of Minnelli’s catalog of films, Griffin gives us the dope on the off-camera goings-on during the shooting, in this case a rivalry between Ethel Waters and the exquisite Lena Horne, whom the former felt was getting too much attention from the director. The movie’s unequivocal success launched Minnelli’s film career at MGM. His next major achievement would be directing Judy Garland at her Technicolor loveliest.

Speculation about the director’s sexuality fills the pages, as do critiques of his directing style. Various interviewees cite Minnelli’s cryptic communication skills, his obsessive preoccupation with inanimate visuals, and his penchant for insisting on specific line readings. While deliciously entertaining, Griffin’s attempt to reveal the man behind the man behind the camera leads us only to more speculation. To say that Minnelli had interjected secret codes into projects such as Tea and Sympathy, the story of an effeminate man wrongly perceived as gay, seems strained. Minnelli undeniably had a “queer sensibility” in that he was able to bring empathy to his characters, most of whom were outsiders struggling with their inability to reconcile their inner self with the world around them. But the director worked in a busy studio from one project to the next and was apparently more concerned with his career than with expressing his true self.

Minnelli worked at MGM for over two decades, earning a reputation primarily for his musicals. While 1951’s An American in Paris took home six Academy Awards, including Best Picture, he didn’t win the Oscar for Best Director until 1959, for his spectacularly lavish Gigi. He also took on comedies such as The Long, Long Trailer and Father of the Bride. But the director’s meticulous attention to detail and flair for the visual resulted in much of his non-musical work being dismissed by his contemporaries as more style than substance. Some of his classic melodramas, such as Lust for Life, Some Came Running, and The Bad and The Beautiful, are now receiving some long overdue praise.

The reader is certain to find a hundred or more new items that Griffin has uncovered in his exhaustively researched biography. One is that Minnelli had a developmentally handicapped older brother, Paul, a sibling that he seems to have forgotten in his misremembered memoir, ironically titled I Remember It Well. Another surprise might be the existence of another daughter, Christiane Nina (“Tina Nina”), from his second marriage, to Georgette Magnani. However, if you’re expecting to find out who the real Minnelli was, you may still be left wondering. As psychiatrist Marc Chabot says to Daisy Gamble in On a Clear Day: “I used to be in love with answers, but since I’ve known you I’m just as astounded by questions. Answers make you wise, questions make you human.” Griffin’s biography contains plenty of each.

Dean Wrzeszcz is a contributing editor at Gay City News and a journalist based in New York City.